This week I’m going to be writing about the planes. Tomorrow I’ll be posting a long article about the Endless Night, and later in the week I’ll be addressing some questions from my Patreon supporters. I thought we’d start off with a few of the most basic questions. Something that comes up fairly often: Why did we create a new cosmology for Eberron?

The Great Wheel has lingered through many editions of D&D, and most official settings use a variation of this planar cosmology. But when we hammered out the details of Eberron, we made a conscious choice not to use the Great Wheel, but rather to create an entirely new cosmology from the ground up. Why?

One of the main goals in creating Eberron was to create a new world — a setting that could support stories that couldn’t be told in other settings. This included taking a different approach to the divine. Forgotten Realms had long received the most support of any D&D setting, and divine intervention and interaction plays a significant role in Faerun. But while active gods allow for tales like the Time of Troubles, they don’t work well when you want to deal with stories of schisms, corruption in a church, crusades and inquisitions that may have noble intent but which will clearly bring suffering. These are things that feel real and that we’ve dealt with in our history… but things that could easily be resolved if a deity could simply appear and say “You’re doing it wrong” or clarify a point of heresy. For this reason alone, we had to create a new cosmology. The planes of the Great Wheel are the homes of the gods; if we wanted a universe where the existence of the gods is a matter of faith, we had to start with a clean slate.

Setting gods aside, we wanted to start from scratch because we wanted to look at everything with new eyes. Eberron takes a different approach to gnomes. It takes a different approach to drow, to elves, to gnolls. Why wouldn’t we take a unique approach to fiends and celestials? If you want to use the Blood War or the Great Wheel in your game, there’s a dozen settings where you can. And for that matter, if you want to use these things in EBERRON you can, because you can always just change the universe to incorporate them.

In short, the Great Wheel already exists for those who want it; developing Eberron was an opportunity to explore a different approach to the planes. In Eberron, the planes aren’t tied to gods. They aren’t worlds tied to particular alignments. Only one of them is any sort of afterlife. Instead, they are isolated aspects of reality given concrete form. And part of the reason for doing this is because each one is a unique and fascinating place to explore… although, unfortunately, we never had the opportunity to explore them in third edition.

Did you establish the 13 Eberron-exclusive planes to discourage world-hopping from other settings, and if so why?

It was never our intention to discourage plane-hopping. If you look at page 92 of the Eberron Campaign Setting, it explains that the material plane of Eberron AND its thirteen planes are surrounded by the transitive planes: Astral, Ethereal and Shadow. From the start, Chris Perkins asserted that the Plane of Shadow connects all settings — if you wanted to get from Krynn to Eberron, you could get there through the Plane of Shadow.

With that said, while the ECS mentions the Plane of Shadow, it doesn’t CALL OUT that it could serve as a bridge between settings. Like many things in Eberron, we wanted to leave options to help GMs tell the stories they want to tell. It wasn’t our intention to discourage world-hopping, but it also wasn’t our intention to encourage it. Eberron is a self-contained setting with more than enough ways to add almost anything you want to use… and once you DO start bringing things in from other settings, it opens up various cans of worms, like what happens if a god from another setting comes into Eberron? Why are couatl in Eberron so different from couatl in other settings? But if you want to do it, it’s easy to do it. The Plane of Shadow is one option, but it’s a trivial matter to come up with others. Cannith’s created a world-hopping eldritch machine. The Mourning has torn a hole between realities. And so on.

Syrania is peace and Fernia is fire, Dal Quor is dream and Daanvi is order. What *does* the plane of Eberron represent and why is it in the center? And why does it not have any weird planar rule based on some concept?

There’s a bunch of things to unravel here.

First of all, Eberron isn’t the plane “of” anything. As called out in the Eberron Campaign Setting, Eberron is the Material Plane… which means it’s explicitly the plane of everything. From a mythological perspective, the planes were created by the Progenitors; when they were done, they created the material plane as a nexus where all those concepts overlap. The material plane is a place where you have order and chaos, strife and serenity, life and death. This is also why Eberron is where you find the most mortal creatures, as mortals are poised between many things.

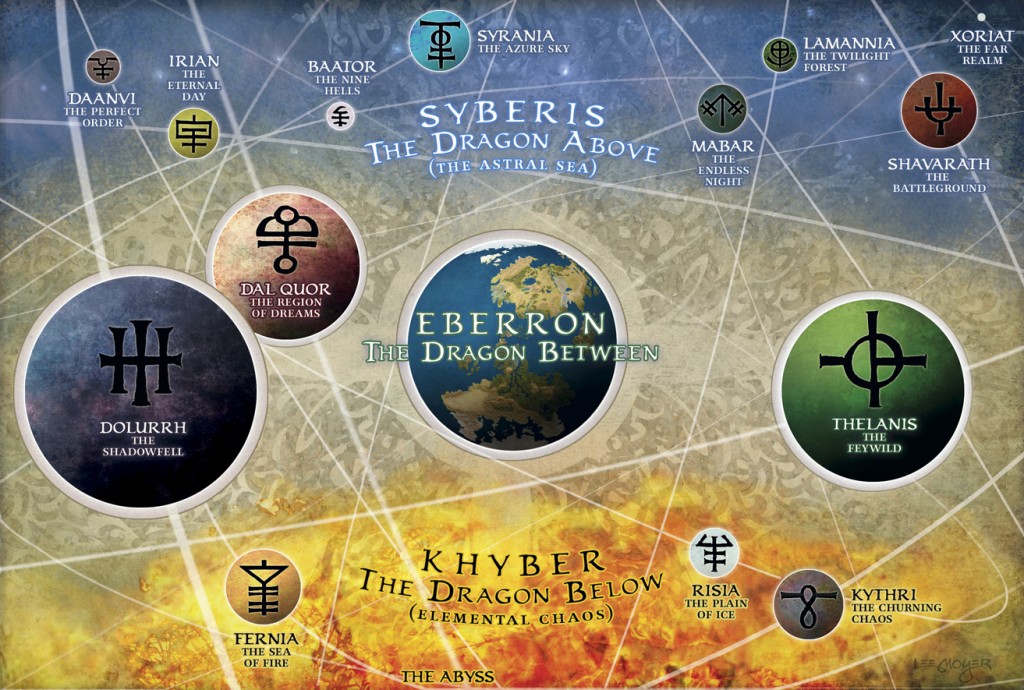

With that said, I also think that the planar orrery — pictured above – is a metaphorical way to depict the planes. They aren’t actually little planets orbiting Eberron; they are layers of reality that exist sideways to Eberron. But because they move in and out of alignment in a predictable fashion, the orrery is a convenient way to depict them. And Eberron is at the center because it touches all of them, while they don’t directly touch one another.

Many of these concepts (order and chaos, war, nature, fairy tales, madness, death) are human at their core and while a lot of the intelligent species of Eberron share a lot of these notions… they also have many of their own, very relevant to them and only barely important for humans. Bloodlust for vampires. The Prophecy for dragons. And on that topic, this is a dragon centric world! Shouldn’t there be a plane of mystic secrets and a plane that’s avarice?

Life and death. Order and chaos. Strife and serenity. These aren’t concepts that are relevant to a single race; these are fundamental things experienced by almost any natural creature. In some ways this is the definition OF a “natural” creature — you live, you die, you are part of the natural world. There is chaos in nature and there is order, conflict and peace. These aren’t somehow human concepts; they are the basic pillars of reality.

Part of the issue here is that you shouldn’t look at the planar concepts with a narrow focus. By simple description Xoriat is the plane of “Madness” – but in fact it is about the alien and unknowable, the unnatural, about questions you shouldn’t ask. Madness is a potential consequence of contact with Xoriat and an easy label for it, but the actual concept that defines the plane is far broader and more flexible than that; the illithids call it the Realm of Revelations. Thelanis is the Faerie Court, but it is also the plane of stories and of magic, of the wonder we want to be in the world. Dolurrh is where spirits go after death, but Mabar is the plane of Death; it is entropy, the hunger that consumes both light and life, the shadow that waits for every light to fade. Irian is the positive force that drives and encourages life, the sun about to rise and the light waiting to banish the shadow. “Peace” is an easy way to describe Syrania, but it’s far more than that. I wish I had time and the ability to delve into every plane in more depth, and I’ll touch on these later in the week. But again, if they seem simple, it’s because the simple concepts are all most humans understand. But that’s a limitation of perception and imagination.

So taking the concepts mentioned – bloodlust for vampires, mystical secrets or greed from dragons – these are narrow ideas and already incorporated into the existing planes. Martial fury would be a part of Shavarath, while the consuming hunger of the vampire is a symptom of its tie to the endless dark of Mabar. Mystic secrets fall under Thelanis or Xoriat, depending if learning them could drive you mad; and as for greed, there’s likely a Quori who feeds on dreams of avarice. Dragons live and die. They dream and they tell stories. Vampires may not die, specifically because their tie to Mabar keeps them from Dolurrh… but they pay for that life by consuming the lives of others. They are surrounded by nature, by fire and ice. The planes define reality. Vampires, dragons and humans all just live in it.

If the Astral surrounds the entirety of the “universe” of Eberron, what lies outside the Astral?

What do you WANT to be beyond the Astral? It’s not something we’re likely to define in canon, both because it’s far outside the scope of a typical campaign and more important, because leaving it undefined creates opportunities for GMs to come up with an answer that works with the story they want to tell. A few possibilities:

- Nothing lies beyond the Astral. We’re not bound by the laws of nature; it could be infinite and empty, extending endlessly into eternity.

- Beyond the borders of the Astral lies the Far Realm. Perhaps, if survive your exploration of the Far Realm, you’ll find other astrals and other universes drifting beyond it. The main issue is that you’ll want to think carefully about how you distinguish the Far Realm from Xoriat (something I discuss in the recent Xoriat post).

- Perhaps the Great Wheel lies beyond the Astral. Perhaps the Progenitors were rogue deities from the Wheel who made a new creation in secret, hidden away where the other gods couldn’t find it and meddle with its inhabitants.

There are just a few ideas. The question is what do you need the answer to do for you? Do you want the opportunity for players to explore other settings? Do you want a bizarre threat that’s so completely alien that even Xoriat is creeped out by it? Choose the answer that tells that story.

That’s all for today. Tomorrow I’ll explore the Endless Night, and later in the week I’ll answer more questions from the Patreon Inner Circle. Thanks to everyone who’s supporting the site!

It’s long time i’d like to ask: ehi is gong to dolurrh? Only humans and demihumans? Orcs? Animals? Dragons? Giants? Is there a rule on who can be found there (and eventually brought back)?

The general principle is that anything that has a soul goes to Dolurrh. An easy rule of thumb for “Does it have a soul” is “can it be resurrected.” In my opinion, dragons, orcs and giants can all be found in Dolurrh… though they may not all be found in the same LAYER of Dolurrh, any more than they exist in the same space on Eberron.

I’m looking forward to talk about Irian in particular — provided, of course, you’re allowed to. Many of the planes that haven’t been given any attention in Eberron’s canon at least draw clear parallels to classic D&D planes… but Irian has the least to go on. It strikes me as more distinct from the classic Positive Energy Plane than Mabar is from the classic Negative Energy Plane, and while it’s neither a good nor evil plane, sources of conflict are less obvious for it than for Mabar.

When I used it in my own game, I drew from Dragon #321’s hypothetical Plane of Radiance and the feel of lighthearted 80s cartoons — and, of all things, a line from the video game Kingdom Hearts inspired me to include a rare type of villain among the local mortals (said mortals being glimmerfolk, taken from the aforementioned Dragon). With these thoughts in mind, I winged it. I assumed that coterminous periods with Irian normally involved peaceful trade, and the consequences of a lightstealer being in the area that corresponded to Sharn came as a nasty surprise the PCs had to deal with.

In general, it seems to me like many of the planes ought to involve tonal shifts relative to the Material Plane. It doesn’t seem like there ought to be a lot of noir in Syrania, for instance.

I just posted an extended look at the Endless Night, which is to say Mabar. I’ll be posting a shorter look at Irian on Wednesday, but in many ways it is the reverse of Mabar: a place of beginnings and of hope. And certainly – it’s not a place with a lot of room for noir.

Wow, I’m sorry to come a month late to this discussion, but thanks for the comments on the planes and for answering my question about vampires and dragons.

In The Shattered Land, the Sulatar seemed to be waiting for the promised in Fernia.

It seems like Fernia is a pretty easy plane to get into. Coterminous every five years?

So why has it taken tens of thousands of years for thr dark elves to figure out how to get there?