The coldfire lantern hanging from the ceiling? That flickering’s due to a poorly etched sigil. Give me five minutes and a crown’s worth of residuum and I could have it steady and brighter. There’s a crack in the cleansing stone, and if it continues another inch it’s going to start soiling instead of cleansing. But that’s not the worst of it. In my mind I can see a better design. I could make a cleansing stone that’s half the size, using half the shards, that would make colors even brighter. I can see it. I could make it. I know I could. I just don’t have the time.

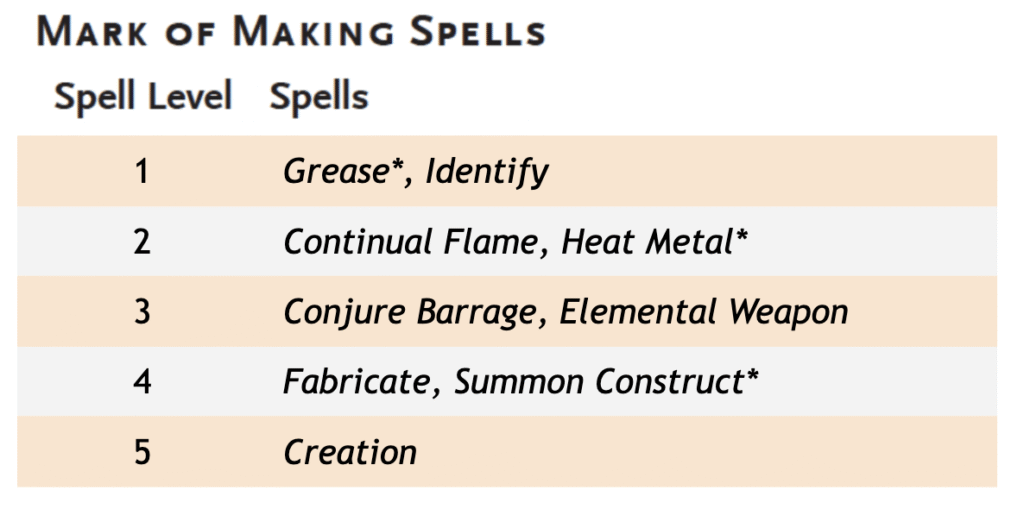

The Mark of Making provides an intuitive bonus to any ability check made using Artisan’s Tools. This isn’t Proficiency, though it stacks with it; it’s an intuitive understanding of tools. Weaving, painting, baking, smithing—you instinctively know how to make things. This guidance goes beyond the mundane. The Mark of Making provides the same intuitive bonus to any Intelligence (Arcana) check, and anyone who carries the Mark has the ability to cast Magic Weapon once per day. Magic comes naturally to you, and one of the first things you learned to do was to weave it into wood and steel. So when you look at a weapon, you know you could improve it. When you see a broken object, you know you could mend it. And if you had the tools and the time, you know that you could make something better.

For some Cannith heirs, this knowledge becomes an obsession. They can’t pass by a broken object without Mending it. Others may seem socially awkward or absent minded, because the designs they’re working through in their minds are always more interesting than the conversations around them. But for most Cannith heirs it’s a background detail and a point of pride. They are confident in their skill, and find it soothing to create things; Cannith heirs often have some project they’re working on, something small that keeps their hands busy. But they don’t have to work on it at all times; they can set it aside to focus on the needs of the moment.

House Cannith has long been seen as the most powerful Dragonmarked House and the heart of the Twelve. In part, this is due to the commercial success and wealth of the house. Cannith goods have long been part of everyday life across the Five Nations, from the Everbright Lanterns that light the streets to the coaches that drive along them. Cannith supplied the armies that fought in the Last War, producing arcane artillery, armor and weaponry for soldiers, and with the warforged, soldiers themselves. But beyond that, many Houses rely on Cannith for the tools that are integral for their success. The Lightning Rail, Elemental Airships, Speaking Stones—all of these were designed with the assistance of Cannith artificers and produced in Cannith factories. This in turn has nurtured a cultural arrogance within the House itself; Cannith heirs consider themselves the equals of any noble, seeing their House as the greatest power in Khorvaire. At least they did until the Mourning. The loss of Eston and of the Patriarch Starrin d’Cannith has sown the seeds of chaos. Almost every heir supports one of the three leading candidates to replace Starrin, and no compromise has emerged in the last four years. The divided House was unable to block the edict in the Treaty of Thronehold that shut down the creation forges, further weakening House Cannith. The House continues to move forward, sustained by its infrastructure and its momentum, but pressure is building. If the House can’t mend itself and unite behind a single leader, it could soon splinter into three.

THE MARK OF MAKING

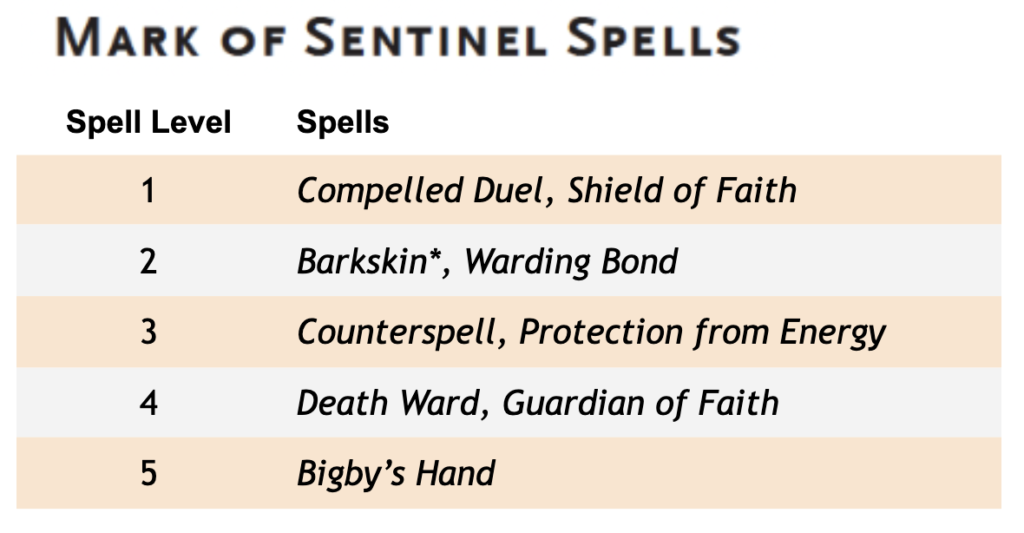

The most basic gift of the Mark of Making is Mending—the ability to repair things that have been broken. While the most obvious manifestation of this cantrip is repairing a break or tear, in my campaign I also allow it to undo other sorts of minor damage: smoothing out dents, restoring burnt cloth or leather, lubricating rusted metal, and similar minor transformations. Cannith Tools amplify these gifts in small and sustainable ways, while the Spells of the Mark allow a Cannith Heir to perform instant, dramatic effects. Some say the Mark of Making draws on Onatar’s Forge while others claim it’s tied to the Fires of Fernia. Whatever the truth, a Dragonmarked heir can instantly Heat Metal or Grease a surface. Fabricate allows an heir to visualize a creation and use the Mark to impose their vision upon raw materials; while the ultimate power of Creation manifests matter from pure arcane essence to make the vision real. This is also the basis for the dramatic Conjure Barrage, which allows a Cannith heir to temporarily create a swarm of weaponry.

Summon Construct lies between Fabricate and Construction. While the spell normally requires “a lockbox worth 400 gp” as a nonconsumable material component, when cast with the Mark of Making the caster instead needs to be holding a set of Artisan’s Tools with which they are proficient. While no materials other than the tools are required to cast the spell, Canith heirs usually draw on raw materials in the area and fill in the gaps with manifested matter; the final appearance of the construct depends on the materials used and the imagination of the heir. Many younger heirs manifest constructs similar in appearance to warforged, because they are used to working with warforged; but others could create animated armor, metal insects, or even clockwork beasts. When the spell expires, the manifested matter dissipates and the construct collapses back into raw components. Regardless of the materials used to create the construct, when it is summoned the caster decides whether it possesses the Heated Body, Stone Lethargy, or Berserk Lashing trait.

An heir capable of casting Spells of the Mark can cast Identify as a ritual. Here again, the heir needs to have a set of Artisan’s Tools they’re proficient in rather than the traditional pearl component; when casting Identify, the heir is essentially running a series of tests on the object they are studying. Meanwhile, Magic Weapon is a fundamental power of the Mark that any heir can cast—while those with access to Spells of the Mark can master the more powerful Elemental Weapon.

Kanon vs Canon. Three of the spells on the list above are marked with asterisks, and that’s because they vary from what’s presented in Forge of the Artificer. In the original Eberron Campaign Setting, two of the Mark of Making’s spells were taken up with Repair Damage; Mending was a full spell rather than a cantrip; and Creation was split into two spells. So in translating the Mark of Making to 5th Edition, there’s a lot of space to fill… but I don’t love the choices made in canon. I associate Cannith with metal, so using the Mark to lubricate and heat metal makes sense to me—more sense than Floating Disk and Spiritual Weapon, both of which are more about projection of force and levitation. At 4th level, I prefer Summon Construct to Stone Shape. I don’t feel like stone is something we’ve called out as playing a major role in Cannith, while constructs have been part of its story since the first Gorgon!

ARCANE FORGES AND CREATION PATTERNS

The most iconic tool of House Cannith is the Creation Forge used to create the Warforged. These eldritch machines draw on the full potential of the Mark of Making, working with the principles of Creation and Fabricate to manufacture construct bodies and draw the spark of life into them. The Treaty of Thronehold demanded that House Cannith shut down its Creation Forges and cease the production of Warforged, and the House appears to have done so. But the Creation Forges are just one of the many arcane tools House Cannith employs to streamline its production process. Arcane forges are stationary tools that amplify the powers of the Mark of Making. The standard arcane forge can only be operated by someone with the Greater or Lesser Mark of Making—which is to say, someone who can cast Fabricate as a Spell of the Mark. Arcane forges are limited in a number of ways.

- A forge requires a Schema, which is a blueprint for a particular object. The forge has to be attuned to the Schema, which takes time; so on a typical day, an arcane forge is only producing a specific thing.

- Most arcane forges are specialized tools that can only work with a particular type of material—metal, wood, stone.

- Likewise, most arcane forges are limited in the size and complexity of object they can fabricate.

- An arcane forge requires a small amount of residuum (refined eberron dragonshards) to operate. This is a minor cost that’s far outweighed by the speed and efficiency of the forge, but it is a requirement nonetheless. In the past, this has been a limitation on how many forges the house could operate. The rise of House Tharashk ensured a steady flow of dragonshards, which has allowed Cannith to expand its use of arcane forges.

A Grand Forge provides access to the full scope of Fabricate, allowing an heir to, for example, produce a fully formed longsword from the raw materials presented. However, the more common Base Forge is typically used to produce components which are then assembled by workers on a line. It dramatically speeds production and helps to ensure uniformity of product, but it’s still a process that requires a significant amount of human labor. Whether using a Base Forge to produce simple elements or a Grand Forge to produce finished goods, the heir operating the forge is required to be proficient in the type of tool that would normally be used and to make a check to ensure the quality of the product. In essence, the heir walks through the process of production in their mind and the forge uses the Mark of Making to make it real. While the operator has to have the ability to cast Fabricate through their Mark, they don’t actually cast the spell when using a forge; like a Sivis heir operating a Speaking Stone, it’s something that they can repeat indefinitely—provided they have rare materials and residuum.

Arcane Forges are a form of Eldritch Machine. They’re large, stationary objects tied to a specific f. However, Cannith has smaller tools that help them accelerate production. Creation Patterns are metal rods or tablets engraved with arcane sigils. A Creation Pattern holds the imprint of a particular magical device. This reduces the time and cost to create the item embedded in the Pattern by 33%, provided the artisan has the Mark of Making and has access to the Pattern throughout the creation process.

FOCUS ITEMS

House Cannith is the primary source of Dragonmark Focus Items in Khorvaire. Cannith heirs regularly make use of Dragonmark Channels, Dragonmark Reservoirs, and Channeling Rods. Exploring Eberron calls out that House Cannith can produce objects that duplicate effects of existing magic items but with the additional requirement of having the Mark of Making to use them. A few examples of these…

- Onatar’s Gift has the powers of an All-Purpose Tool. A +1 Onatar’s Gift is standard issue for any capable Cannith Artificer, and is generally shortened to Ony—as in, “You got your Ony?”

- Cannith’s Marvelous Miniatures are identical in effect to Quaal’s Feather Tokens, but they appear to be small metal objects in the shape of the token effect (Anchor, Bird, Fan)

- Talin’s Compact Constructs duplicate the effects of Figurines of Wondrous Power, but they appear to be articulated metal models rather than statuettes; they expand in size when activated.

- Merrix’s Instant Fortress works like Daern’s Instant Fortress; the Cannith model was created by the same artificer who developed the Warforged Titan (the grandfather of the current Merrix d’Cannith).

- The Apparatus of Cannith is similar in effect to the Apparatus of Kwalish. Cannith developed the Apparatus over the course of the last decade as a potential submersible for use in the Last War, but has been unable to produce a version that doesn’t require the use of the Mark of Making.

The idea is that all of these items are drawing on the power of the Mark of Making. In the case of the Compact Constructs, Instant Fortress, and Onatar’s Gift, the item literally builds itself when activated, using the principles of Creation to fabricate temporary matter. In the case of the Apparatus, the idea is that the heir has to use the power of the Mark of Making to keep the Apparatus stable and functioning. I might allow a player character Artificer (especially a Battle Smith) to operate an Apparatus of Cannith, with the idea that they can use their own remarkable skills to hold things together. So in choosing Focus Items for Cannith, look in particular for things that are used to create objects or that could be depicted as creating themselves. The Rod of Lordly Might is another example of this, with the idea that the Rod constructs and deconstructs the various weapon forms it can take.

THE HISTORY OF HOUSE CANNITH

Cyre was said to be the heart of Galifar, and with good reason. The central region of Khorvaire is blessed with a blend of fertile soil, abundant resources, and beneficial manifest zones. When humanity spread across Khorvaire, the Metrol League was quick to prosper. Initially a single city, the League expanded to include the city-states of Metrol, Eston, and Tolan. The Mark of Making appeared approximately 2,500 years ago, appearing in three families. The Harns of Tolan traced their roots to Nulakesh in Sarlona, and had established a reputation as armorers and weaponsmiths; the first marked heir, Costa Harn, forged a set of magic swords that would feature in countless legends and tales in the centuries to come. The Vowns of Eston were Pyrinean. Eliasa Vown declared her Dragonmark to be a blessing from Onatar, and she crafted reliquaries and Octograms charged with mystic power. The Jurans were wanderers with Rhiavhaaran roots. They traveled the roads between the great cities, carrying goods and news and using their skills to repair broken things. Ellos Juran gained renown for his ability not just to fix broken things, but to transform wood and steel into finished goods. Each family prospered in their own way; the most dramatic moment came in the following century when the heirs of Costa Harn led a coup in Tolan and seized control of the city. They placated the other leaders of the Metrol League by promising a tribute of Harn weaponry. They shifted the city itself to support their vision, fortifying it and building up its foundries and its forges; it was Castela Harn who changed the name of the city to Making as a celebration of her family’s skills.

The reputation of the Making families grew over the course of decades, as their goods spread out to distant markets; the warlords of Karrlakton and Korth prized weapons forged in Making. It was Dedra Vown who engineered the alliance of the Making families. A charismatic woman with a grand vision, Dedra wooed the Jurans and Harns with stories of the marvels they could create if they pooled their resources and diverse talents—not to mention the economic advantages to building a regional monopoly. Cannith was the name of a legendary shrine of Onatar in Sarlona, and Dedra convinced the others to join together as the House of Cannith. Castal Harn and Dedra Vown were wed, and it was said at their time that they gave birth to a Gorgon, as this was the first joint product they unveiled. As centuries passed, the House of Cannith prospered. They developed the first Arcane Forges, which were initially used primarily to refine ore—turning raw iron into ingots of fine steel. They developed the earliest form of Magecraft. As the house extended its reach across Khorvaire, they eagerly sought out new arcane techniques and tools, sending adventurers into ancient ruins and adapting any innovations they found in other cities (as they would one day use Desa Cane’s Truelight Lamp as the model for Cannith’s Everbright Lantern). One of the most remarkable forces they encountered were the Edoros of Thaliost, a family of innovative alchemists. Though the Edoros didn’t carry the Mark of Making, their skills and techniques were so valuable to the House that it slowly absorbed the entire family. Today the Edoro are considered one of the founding families of House Cannith, and the Mark of Making is firmly rooted in their lines.

House Sivis and House Cannith both claim credit for the early unification of the Dragonmarked Houses. Cannith accounts say that the Vowns considered the Dragonmarks to be blessings of the Sovereigns and thus thought it logical to bring them together—not to mention profitable—inspiring others with their own structure and organization. Whoever laid the bricks, it was the War of the Mark that served as the mortar, laying the foundation of the Houses as we know them today. As the Houses initially spread, it was natural for them to forge alliances through marriage. The Harn line of House Deneith is one of the few concrete relics of this time, reflecting strong ties between the weaponsmiths of Metrol and the warlords of the north. This blending of bloodlines produced a wave of Aberrant Dragonmarks. It took generations for people to truly recognize the impact of this—critically, that someone who manifested a “mixed mark” lost all connection to the Dragonmarks of their parents and couldn’t pass either Mark to their own children. While this was a general concern to all of the Dragonmarked families, the Vown in particular saw it as an act of blasphemy. If the Dragonmarks were gifts of the Sovereigns, and crossing the lines both produced an unpredictable, dangerous Mark and stripped the bearer of their former connection to the Sovereigns—how could this be anything but the work of the Shadow? While the Vowns were driven by religious fervor, the Lyrrimans of House Sivis recognized the power of a manufactured enemy to bring people together and willingly embraced and amplified the Vown message. This was the beginning of the War of the Mark. Sivis and Phiarlan propagandists worked together to spread terrifying tales of Aberrant Dragonmarks, some based in truth and others entirely false. As Deneith troops armed with Cannith weapons pursued Aberrants across the land, most people believed that the Dragonmarked forces were heroes defending them from a deadly threat. The War of the Mark showed what the Houses could accomplish when they worked together, and the leaders of the houses weren’t about to let that go. Hadran Vown Cannith and Alysse Lyrriman Sivis forged the proposal for a permanent alliance between the Dragonmarked Houses—though it was the architect Alder Juran who pushed to have that alliance named The Twelve.

The next great shift came with the rise of Galifar Wynarn of Karrnath. House Deneith strongly supported Galifar’s ambitions, believing he would succeed where Karrn the Conqueror failed. Deneith arranged negotiations between Galifar and the Twelve, and pushed the other Houses to accept the terms of the Korth Edicts. This placed significant limits on the political and military power of the Houses, but promised them vast economic influence. House Cannith was severely impacted by this, as the Harns were the Lords of Making and the House had vast holdings in Eston. But while the House would have to give up its absolute claim, Galifar promised they would retain their enclaves and forgeholds. This was accomplished in part by Galifar’s dismantling of the nobility of Metrol, a more severe restructuring than took place in any of the other Five Nations; Galifar built his new nation of Cyre around the pillars of House Cannith.

House Cannith prospered during the golden age of Galifar, helping to support the expanding infrastructure of the united kingdom. Cannith steel and the Flying Buttresses supported the great towers of Sharn. New enclaves and forgeholds were established throughout the Five Nations; while Making continued to thrive, the House shifted much of its heavy industry to Breland. While the House made a slow and steady profit, this period also saw it splinter into what Baron Starrin d’Vown once described as “The hundred kingdoms of Cannith.” Viceroys and ministers built their own tiny empires, diverting funds for their personal projects. Rivalries escalated between forgeholds. This was never so severe as to threaten a true splitting of the House itself, and some of the Barons even encouraged these little wars; overall, House Cannith continued to grow and prosper. But it’s a key aspect of Cannith’s culture that can be seen throughout the Last War and in the present day. A strong Baron could hold the House together and force it to move in a single direction—but the Cannith Seneschals were always looking out for their own projects and interests.

As centuries passed, Cannith helped construct the Orien trade roads and spread everbright lanterns throughout the kingdom. Speaking Stones, Elemental Galleons, the Lightning Rail—these were remarkable innovations that transformed daily life. And yet, these advances occurred slowly. Cannith and Galifar both grew at a careful, steady pace. It was King Jarot ir’Wynarn who shifted this tempo. Some say Jarot was shaken by the events of the Silver Crusade, or even by reflection on the Year of Blood and Fire that had rocked Thrane centuries earlier. By some accounts, Jarot feared armies rising up from Khyber; others claim he was certain that the forces of Riedra were preparing to invade. Whatever nightmares drove him, King Jarot demanded that the Twelve provide him with weapons. Not just arms and armor for common soldiers; Jarot urged Cannith to devise new forms of arcane artillery and to “Change the face of war.” Across Khorvaire, forgeholds devoted to civilian goods shifted to produce tools of war. Soon the hundred kingdoms of Cannith were competing, each seeking to shine. Hungry for inspiration, Cannith Viceroys launched a new series of expeditions to search for forgotten secrets; Cannith teams traveled to Xen’drik, explored Dhakaani ruins, and even made their way into the Demon Wastes.

Cannith’s achievements over the course of the Last War are too numerous to list here. With each decade, they improved the design of their Siege Staffs, Long Rods, and Blast Disks. The development of the Warforged forever changed life in Khorvaire; what began with the semi-sentient Warforged Titan ended with the terrifying Warforged Colossus. Throughout the course of the war, the competition within the house continued, with each Viceroy vying for resources, each determined to make the next stunning breakthrough. Of course, Cannith didn’t want to create a weapon that would end the war; the perfect weapon was one that required rival nations to purchase their own counter to it. Cannith thrived in the Last War… until the Mourning.

The Mourning devastated House Cannith. The death of Baron Starrin created a crisis of leadership. But beyond the loss of a leader, Cannith lost its oldest and most important enclaves—the centers where young heirs of the House were raised and trained. It lost a host of forgeholds and factories, the full impact of which is yet to be seen. Cannith forgeholds aren’t interchangeable. White Knight was a small forgehold near Kalazart that focused on the creation of Focusing Nodes. While these have no function on their own, they are crucial to maintaining the flow of power through large-scale arcane systems—and as such, are necessary for the creation of a Lightning Rail engine, an Elemental Airship, a Warforged Colossus, a Floating Fortress, or anything of similar size. This is just one example of a specialized facility that supplied Cannith forges across Khorvaire; the wounded house is scrambling to repurpose existing facilities to compensate for what was lost in Cyre. Other forgeholds were engaged in research that had been intentionally held in isolation by the Holdmaster—potentially decades of specialized work now lost to the House. Beyond forgeholds and enclaves, Cyre held countless Cannith warehouses filled with raw materials and finished products. The Mourning claimed vital resources, facilities, skilled staff, and House officers, along with historical records and relics of the House; it was a shattering blow.

The surviving officers of House Cannith—the Seneschals and Viceroys—gathered in Sharn at the end of 994 YK. Over the course of a week of meetings, these ministers developed plans that would allow the Fabricator’s Guild to continue to operate, redirecting supply lines and resources to account for the loss of Cyre. But try as they might, there was no consensus on a replacement for Starrin d’Cannith. There was a formal process for succession that traditionally occurred in Eston, with relics, rituals, and a vote amongst the officers. But Eston and its relics were lost, and many of the ministers were dead and had yet to be replaced. In addition to a bitter divide over the proper candidate, many ministers insisted on filling the empty offices first and attempting to reclaim lost relics, either out of a legitimate loyalty to tradition or a belief that more time would help their chosen candidate gain additional support. Ultimately, the Sharn Accords split House Cannith into three administrative regions, each overseen by a Baron; the Accords dictate that the officers of the House shall gather at Vult each year to discuss the process of succession.

This is the state of things in 998 YK. The House remains divided in its loyalty to the three Barons. It remains to be seen if one of them can restore the House to its former glory, or if the House will fracture. But should House Cannith break apart like the Shadow Schism of Phiarlan and Thuranni, the smaller Houses would be far weaker than the Gorgon of old. Cannith South and Cannith East rely on alchemical solutions produced by Cannith West, while Cannith South has the bulk of the steelworks; a full separation would dramatically limit what each of the smaller factions could produce.

What Happens Next?

- Just How Bad IS House Cannith? Eberron is a setting in which the DM is expected to make key decisions about their version of the world. One of those questions is whether House Cannith is a villainous force. Cannith can be presented simply as a resource that produces useful tools for adventurers. Its inventions are a vital part of everyday life. On the other hand, it’s possible to present House Cannith as a force that acts with ruthless efficiency to maintain its monopolies, stifling or stealing independent arcane resources, acting carelessly in its dangerous research (IE did it cause the Mourning?), and using its economic power to demand favors from governments, criminal organizations, or others who rely on its services. You can present the typical Cannith heir as feeling remorse for the fact that the House treated Warforged as weapons, or you can present the House as having no sympathy for the Warforged and scheming to regain control of the Creation Forges and the Warforged themselves. Canon material generally walks a middle line between these extremes; it’s up to the DM to decide what’s true in their version of the world.

- The Three Headed Gorgon. The Sharn Accords split power between three Barons: Jorlanna Edoro in Fairhaven, Merrix Vown in Sharn, and Zorlan Harn in Korth—has a strong case and a faction that supports them. But Cannith is a machine that needs all its pieces working together to prosper. The Sharn Accords have kept it going so far, but if the three factions can’t come to an agreement soon it may begin to break down. Any of the three Barons might employ a capable group of adventurers to help with their schemes, whether they seek to elevate their own standing (recovering treasures from the Mournland, completing an arcane breakthrough, performing a major act of philanthropy) or to sabotage their rivals.

- Profiting from Prophecy. House Cannith’s leadership crisis could be a key decision point in the Draconic Prophecy, with the future taking different paths based on which Baron claims the crown. If this is the case, each Baron could have a greater power promoting their cause. Canon has already suggested that one of the Lords of Dust is influencing Jorlanna. But there could be a different Lord of Dust backing one of the other Barons—perhaps Mordakhesh is supporting Zorlan, knowing that his leadership will lead to devastating war—while the Chamber may be supporting the third Baron. On the other hand, it could be that the fall and dissolution of House Cannith is the outcome an immortal faction is seeking.

- The Bounty of the Mournland. There are countless Cannith facilities in the Mournland, ranging from warehouses stocked with mundane goods to hidden forgeholds where secret weapons were being designed. Perhaps the Mourning itself was the result of an accident at just such a facility—and if that’s the case, the weapon responsible could be there just waiting to be found. Adventurers already exploring the Mournland could stumble onto such things, or they could be hired to recover Cannith goods from the Mournland. The patron could be a Cannith heir, or it could be someone with nefarious intent. The dwarf who pays the adventurers to recover a sealed chest—an extradimensional locker filled with Blast Disks—could be an Aurum arms dealer looking to resell them for a prophet, or they could be one of the Swords of Liberty planning to blow up King Boranel. The lost forgeholds weren’t spared from the effects of the Mourning, and Cannith ruins might contain warped constructs, living spells, tormented ghosts, or even greater dangers.

- Endless Rivalries. House Cannith has always suffered from corporate intrigues and internal divisions. While Zorlan, Merrix, and Jorlanna vie for control, there are countless lesser intrigues between rivals fighting over resources, contracts, and simply for prestige. Adventurers could be employed to steal a rival’s research, to embarrass them at a gala, or any sort of minor scheme.

- The Fate of the Forged. House Cannith created the Warforged and sold them into servitude as weapons. Some heirs of the House seek redemption by helping the Warforged in the present day. Some are indifferent to the overall plight of the Warforged as a species, but seek to continue their research—secretly creating new Warforged, whether using hidden Creation Forges in violation of the Treaty of Thronehold or pioneering new means to create sentient constructs. And then there are those who still consider Warforged to be assets of House Cannith, villains who seek to impose their will on Warforged with tools like the Master’s Summons. On the other side of the equation, there are Warforged who yearn for vengeance on their creators, and others who seek Cannith aid in solving the challenges faced by their species.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO KNOW MORE? This is an excerpt of an article written for my Patreon supporters. The full article is three times the length of this one, and includes the Structure of House Cannith (with details on the Fabricator’s Guild, the Tinker’s Guild, the factions of the three Barons, prominent forgeholds and enclaves, and more), the Families of House Cannith, Cannith Customs, new focus items, and more!

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon