To view this content, you must be a member of Keith's Patreon at $5 or more

Already a qualifying Patreon member? Refresh to access this content.

Those two have been watching you since you came in. The dwarf in the conveniently nondescript chainmail recently drank a Potion of Giant Strength—see the way his muscles are trembling, barely able to contain the power? The Khoravar’s a mage. That’s a wand of Xorian wenge in his hand, so she’s probably an enchanter. Which probably means they intend to take you alive… probably. Do you want to try your luck and see how it turns out? Or shall we discuss my rates for protection?

The Mark of Sentinel sharpens your senses. It provides an intuitive bonus to Perception and Insight. But this isn’t just about keen sight and sharp ears. It’s an intuitive bonus—an instinctive evaluation of all possible threats. The Dragonmark keeps you alert, every ready. When you enter a room, you always check the exits. When you meet a stranger, you’re always searching for signs of hidden weapons or hints as to their combat capabilities. It’s not a conscious thing; it’s been drilled into you and enhanced by your Mark. House Deneith has never abandoned its martial roots. If you were raised in the House, your education was on par with any military academy in the Five Nations. And once you survived your Test of Siberys—whether you manifested a Mark or not—you had to serve a tour in the Blademarks or the Defender’s Guild. Whatever path you’re following now, you were raised in a culture of martial discipline and service.

When creating a Deneith adventurer or NPC, consider how this upbringing has affected them. The majority of Deneith heirs serve as Blademarks or Defenders for their entire careers; that service is all they know and all they need. What about the Deneith you’re making? Do they still serve the house or have they turned their back on it? Or is it something in between—they’re a mercenary licensed by the Blademarks, but they’ve chosen to follow an independent path? Regardless of the answer, consider this. A Deneith heir was raised with a strict code of discipline and bound to a chain of command. Do they maintain that discipline as an adventurer, and possibly seek to impose it on others? Do they want the party of adventurers to function like a military unit? Or have they rejected their upbringing, choosing to celebrate their independence and freedom? Is war second nature to them, or are they trying to bury their blade?

While it varies by family, Deneith heirs tend to be stoic and serious. Heirs of the house were raised to be soldiers, and furthermore, trained to be ever alert for danger. It’s nearly impossible for a Deneith heir to fully relax and let their guard down; it simply isn’t in their nature. Likewise, Deneith heirs are driven by their desire to protect the people and things they care about. In making a Deneith character, consider who or what you’re protecting. Is it your entire adventuring party? Is it a particular individual? Or is a concept—a nation, a faith, a village? This is one of the main reasons heirs end up leaving House Deneith, whether voluntarily or as excoriates. As a Blademark or a Defender, you serve the client only as long as gold continues to change hands. You could be defending a noble one day, and serving their mortal enemy the next day. The House does its best to push heirs to see themselves as, ultimately, defending DENEITH—protecting the family and ensuring its prosperity through their hard work. But there are always Sentinels who develop an attachment to their clients or to ideals beyond pure profit. As a Deneith character, are you driven by gold and the good of your House? Or have found something that’s more important to you than platinum?

Deneith upbringing is much like a military academy, but that doesn’t mean that Deneith adventurers have to be fighters. Heirs initially train with spear, club, dagger, and crossbow, and those that excel at physical combat focus on martial training. But magic is part of everyday life in Eberron, and heirs who have the potential to become Wizards, Sorcerers, or Bards receive specialized training to develop those skills. Blademark mages are trained to focus on Evocation, Conjuration, and other spells that can play a powerful role on the battlefield; those destined for the Defender’s Guild will focus more on Spells of the Mark and personal defense. Meanwhile, a Deneith Bard is primarily trained to lead. They’re warlords, not entertainers; their Inspiration reflects this leadership, and they are driven toward the College of Valor. These paths—martial and magic—are the common choices; heirs without the exceptional potential of player characters will still be tapped as player characters. Other classes could reflect unusual training or focus. The Peacekeepers are an elite force within the Defender’s Guild, trained to protect clients in environments where no weapons are allowed; they are an order of Monks with the Warrior of Mercy subclass. While there’s no schooling for it, Deneith has produced a number of champions whose mastery of the Mark of Sentinel allows them to reduce the damage from attacks; this is a different way of playing a World Tree Barbarian, presenting their Rage and other class features as being manifestations of the Dragonmark. Other classes are less common in House Deneith. A Rogue or Warlock with the Mark of Sentinel likely developed their skills outside of the House; Deneith doesn’t typically traffic with spirits, and while the Peacekeepers are subtle, the Blademark and Defender’s Guild primarily focus on strength rather than stealth. Deneith heirs with a religious calling typically follow this beyond the House. An heir who becomes a Paladin may return to Deneith once they have mastered their gifts, and such champions often become Sentinel Marshals; but the house itself doesn’t have the depth of faith required to train Clerics of Paladins, let alone Druids.

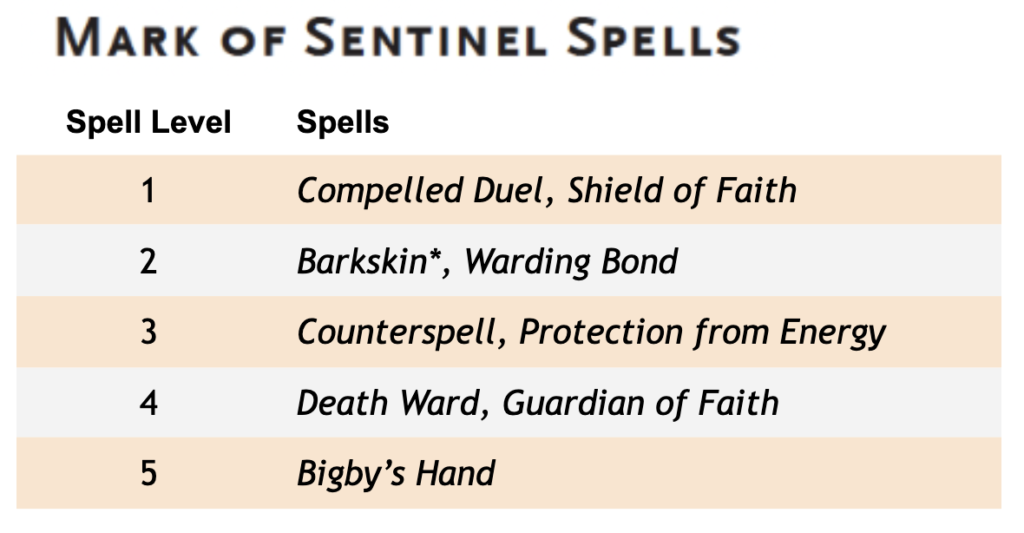

The Mark of Sentinel allows its bearer to protect themself and the people around them. Many of its gifts are straightforward, whether deflecting an attack with a wave of force (Shield) or providing slightly weaker protection over a longer period (Shield of Faith, although no faith is required). Heirs who possess the Lesser Dragonmark can disrupt other forms of energy, as seen with Counterspell and Protection from Energy. Heirs with the Greater Mark have the ability to cast Bigby’s Hand; this draws on the same force manifested with Shield, amplified and wielded with more finesse. Guardian of Faith draws on this same power, manifesting a being formed from this shield energy. Typically, a Deneith Guardian of Faith draws on the appearance of the heir’s family beast—a Ram, Lion, or Dragon. However, there have been heirs of the House whose Guardians have taken other forms; Matriarch Dalia d’Deneith was celebrated for manifesting a full Chimera with her Dragonmark.

Most of the spells of the Mark of Sentinel revolve around the projection or disruption of energy, but there’s a second thread that’s more subtle: Compelled Duel and Warding Bond. While adventurers with the Mark of Sentinel have access to all of its powers, NPCs are often more limited. Deneith NPCs from the Ravan line tend to develop Compelled Duel and Warding Bond, while those of the Wyrn families are more likely to be able to cast Shield of Faith and Barkskin. The children of the Lion—the core Deneith—are equally likely to manifest either or both sets of spells.

Kanon vs Canon. One spell on the list above is marked with an asterisk, and that’s because it’s a change from the list that appears in Forge of the Artificer. By canon rules, the Spells of the Mark for the Mark of Sentinel include Zone of Truth… and I don’t like it. Zone of Truth is a great spell for a Sentinel Marshal, and could be a useful one for a bodyguard. But thematically, it feels quite different from the other spells; it’s about investigation rather than defense. Which ties to the fact that we’ve previously said that it’s House Medani that licenses Truthtellers—Magewrights that can cast Zone of Truth. If Zone of Truth was a core ability of House Deneith, I’d expect Deneith to be licensing Truthtellers. So, in my campaign I replace Zone of Truth with Barkskin. This allows the heir to give a willing individual an Armor Class of 17 for up to an hour, with no concentration required. Thematically, I see it as an extension of Shield and Shield of Faith, describing it not as “giving the target’s skin a bark-like texture” but rather as surrounding them with a faint but noticeable shimmer of energy. This flares up when it deflects a blow, manifesting as a web of blue-purple threads. This is something people have been working with for centuries, commonly used by Defenders to protect charges who either can’t wear armor or aren’t proficient in it. So while the shimmering is subtle, it’s an effect observers will notice and recognize.

Some say war is bound to the roots of Karrnath. The area is infamous for its Mabaran manifest zones, but perhaps Shavarath and Daanvi have a subtler, broader influence. Maybe there are shards of Rak Tulkhesh’s prison buried beneath the great cities of Karrnath, whispering of violence. Or maybe it’s just that the land is cold and harsh, and that the people there must be strong to survive. That, too, is part of the mystery of Karrnath. It’s a grim land, harder on its people than the green fields of Aundair… and yet those born in Karrnath often feel a fierce love for their bleak homeland, finding the more hospitable lands of the Five Nations to be uncomfortably soft and warm.

The Mark of Sentinel was the first Dragonmark to manifest on humans. At that time, what is now Karrnath largely followed the model still seen in the Lhaazar Principalities of the mainland—a scattering of domains carved out by those with the strength to hold them. When the Mark of Sentinel first appeared on Jarla Deneith, she kept it hidden while she mastered its powers. When three of her children developed the Mark, Jarla and her kin used its power to challenge the tyrant Dynass. Though Jarla was slain in the battles that followed, the Deneith triumphed. Jarla’s eldest son, Karrlak, laid the foundations of Sentinel Tower in the city that still bears his name. At that time, almost every heir of Deneith developed the Sentinel Mark, and the legend of these mystical warriors spread across the land. It was a century later when new stories arose of Sentinel-marked champions in other realms—the Wyrns of Korth, and the Ravans of Vedakyr, which was then called Ravanloft. The Ravans were crueler than the Deneith, and ruled through force and fear. The Wyrns were loyal servants of the lords of Korth when the Mark appeared among them, and they remained loyal to their oaths, using the Mark of Sentinel to defend their liege lords rather than turning against them. From the beginning there was bad blood between Deneith and Ravan, and the next century was marked by an escalating series of duels and raids which weakened both families and their cities. The Deneith were valiant warriors, but civic administration proved to be their weakness, especially when plague and famine wracked Karrlakton. This led to the rise of a new leader, whose charisma and strategic brilliance helped him rally the common people of Karrlakton behind him: Karrn. While some tales say Karrn defeated Orrin Deneith in battle, the official account of the house says that Karrn invoked the lords of Korth and their Sentinel Guard and urged Deneith to follow their example. Karrn swore that if Orrin and his family would stand by his side and defend him, they would share in his glory. According to the Annals of Deneith, Orrin believed that Karrn was guided by the Sovereigns of War, and said that the gift his family was given was meant to be a shield, not a crown. In the decade that followed, Karrn’s fortunes soared, and the Deneith prospered at his side. One by one, the great cities fell to Karrn’s blade or submitted to his rule. The lords of Korth chose to join Karrn, and the Wyrn came with them. The Ravan resisted; they were driven from Ravanloft, and Karrn claimed the castle built by the Sentinel family as his personal sanctuary. The Ravans opposed Karrn throughout his campaign, and had things gone another way, they might have fled into the Lhazaar Principalities and remained independent to this day. But during the Battle of the Bastion, Orrin Deneith called out the matriarch Syele Ravan. Orrin said that those who carried the Warrior’s Mark should stand together, and Leodan Wyrn stood with him on this. If Syele defeated Orrin, both Wyrn and Deneith would join with Ravan and oppose Karrn. But if Syele fell to Orrin, the Ravan would join their fellow Sentinels. The Annals say that Orrin compelled Syele to accept the duel through the power of the Mark they both carried, and that magic flowed through all those who bore it, binding them to this bargain. Had Syele won that fateful duel, House Ravan might be a power in the world today. But Orrin emerged victorious, and that was the beginning of House Deneith.

The Sentinel Families stood alongside Karrn as he forged the kingdom of Karrnath and stretched his hand beyond. They fought alongside him as he crossed the river and claimed the lands to the south. And when Karrn went too far—when his army was broken and his forces scattered—it was his Sentinel Guard who saw him safely back to his castle in Ravanloft. Orrin Deneith died in the battle of Daskaran, flinging himself in the path of a ballista bolt that would have slain Karrn. While his death was a blow to his family, the story of Deneith’s commitment and courage spread wide… and when the war was finally over, Queen Lycia of Daskaran sent messengers to Karrnath, seeking a force of Sentinel Guards of her own. It was at this moment that Deneith embraced the path of the mercenary—not bound to a single king, but promising loyal service to any who would pay their price.

Karrnath persisted even after the death of Karrn the Conqueror. Karrlakton remained the stronghold of Deneith, and over time the house expanded its mercenary operations. Karrlakton became the proving ground for a force of soldiers ready to serve under any banner. Over time they spread out across Khorvaire, propping up nobles and warlords and establishing new garrisons in those cities they protected. When the War of the Mark unfolded, it was Deneith that organized and commanded the combined forces of the Dragonmarked Houses… And Halas Tarkanan, who organized the Aberrant resistance, was the son of a Deneith heir trained in the tactics of the House. When the Twelve was established in the wake of the War of the Mark, Deneith was a proud member. In the time that followed, Deneith’s ranks grew. Merchants (and House Orien) employed Deneith mercenaries to guard their caravans. City-states relied on Deneith soldiers to serve as peacekeepers. Some scurrilous accounts suggest that members of the Ravan line engaged in acts of banditry in order to drive up the demand for Deneith’s services, but these accusations were never substantiated.

While Deneith served clients all over the continent, its heart lay in Karrnath. The lords of Karrnath leaned heavily on the House, and more than once Deneith helped “adjudicate” a conflict between heirs. While the House maintained its general principle that the Mark of Sentinel was a shield, not a crown, there’s no denying the fact that they helped the Wynarn family achieve and hold power—and the Wynarns were unmarked cousins of the Wyrn. The ties between House and Crown remained close, and it was common for a Wynarn prince to reside in Karrlakton and to drill with the Deneith. This was the case with the young Prince Galifar. When that prince became a conquering king, the offer he made to the Twelve — the terms of the Korth Edicts — were modeled on the role House Deneith had played throughout the history of Karrnath. Deneith’s endorsement of Galifar played a vital role in pressuring the other Houses to accept the arrangement, and it’s no coincidence that Deneith alone retained the right to maintain significant military forces under the Korth Edicts. Nonetheless, the golden age of Galifar proved to be a challenging time for House Deneith. With the nations united, the people of Sigilstar no longer feared Aruldusk raiders, and the lords of Athandra and Danthaven resolved their disputes through the courts rather than on the battlefield. There was still some need for the Blademarks—defending merchants, battling brigands, suppressing unrest, fighting monsters. But it was clear House Deneith needed to explore new paths, and this led to the foundation of the Defender’s Guild and the Sentinel Marshals. The Blademarks had always served as bodyguards to powerful lords, but now the role of guardian was more important than that of soldier. And the Sentinel Marshals quickly became a trusted force that could be called upon to pursue fugitives from justice and to enforce the King’s laws from one end of Galifar to the other.

One might expect that the Last War would find House Deneith heavily invested in the Defender’s Guild, ill-prepared to take to the battlefield. Little could be further from the truth. In the final years of his reign, King Jarot became obsessed with the defense of Galifar. In addition to building up the Royal Army, Jarot commissioned increasingly powerful weapons of war from House Cannith and called on House Deneith to provide elite units and to prepare reserves. Patriarch Halden Harn d’Deneith could smell blood on the air, and he worked quickly to revitalize the Blademark and to draw together the scattered mercenary bands licensed by the House. It’s worth noting that the Sentinel Marshals largely opposed the Last War, and the Lord Commander Brashin Halar d’Deneith met with each of the rival Wynarn heirs, urging them to honor tradition and to preserve the united kingdom. Some say that Brashin’s assassination, six months after the death of King Jarot, was the true death knell of Galifar.

Once the war broke out in earnest, demand exploded. In most nations, nobles were expected to provide military forces to their ruler. This could be accomplished through conscription, but a lord could avoid this by paying for a unit of Blademarks to take the place of their subjects. Karrnath and Thrane were both culturally well prepared for war and had little need of such forces, but Cyre leaned heavily on House Deneith. Breland adapted over time, but also relied on Deneith in the early years of the war. Coincidentally, this meant that Deneith soldiers were often fighting their distant cousins in Karrnath. Despite this, the Karrnathi rulers respected Deneith’s neutrality, allowing the house to maintain its power in Karrlakton even as Deneith soldiers laid siege to Loran Rath. With that said, there’s a common myth that Blademark soldiers wouldn’t fight other Blademarks. Such a restriction would complicate warfare and seriously diminish the value of Deneith forces. However, there are two motes of truth to this tale. When blooded Deneith heirs faced one another in battle, they would surrender after suffering any injury—a tradition known as the first and felling blow. In situations where heirs expected to face other heirs, they would often carry a baton in addition to their primary weapon, using the club when fighting other heirs. The point being that they would fight, and to the best of their ability, but they would try not to kill their kin. It was also well known that Deneith would pay a ransom for its heirs, so even enemy soldiers would often try to take blood heirs alive. However, when heirs of Deneith fought against licensed mercenaries with no blood ties to their house, no holds would be barred. It was for this reason that Deneith was always seeking to increase the ranks of the Blademarks. When Deneith scouts discovered the strength of the hobgoblin bands in Southern Cyre and the Seawall Mountains, they were all too eager to recruit forces from the clans of the Ghaal’dar. The Ghaal’dar weren’t enacting some carefully planned scheme, and had Deneith shown more restraint or spread the Ghaal’dar forces more widely across Khorvaire, they might have averted the disaster than became Darguun. As it was, the soldier Haruuc recognized the shifting balance of power, and rallied the lords of the Ghaal’dar to support the bloody treachery that followed. In another time, the rise of Darguun might have destroyed House Deneith. But as it was, the nations employing Deneith were simply too reliant on the House to change their ways. But the shadow of that grand betrayal still looms large over the House, and it was this that allowed House Tharashk to gain support for its own mercenary endeavors.

Another point often misunderstood is the relationship between House Deneith and the elves of Valenar. House Deneith didn’t recruit the Tairnadal Elves, and it played no role in their initial arrangement in Cyre. The Eberron Campaign Setting states “When the Last War began, Cyre came under attack from all sides and quickly sought allies. While the Undying Court of Aerenal had no interest in returning to Khorvaire, the Cyrans drew the interest of the Valaes Tairn.” Queen Mishann ir’Wynarn dealt directly with the var-shan Shaeras Vadallia, against the advice of Halden d’Deneith. It was only after Vadallia’s betrayal that Deneith brokered deals with Valenar shans for the services of individual warriors and warbands. Deneith is very careful in how it assigns warbands, and their contracts with the elves hold many penalties for oathbreakers. Notably, each warclan that deals with Deneith has a representative residing in Sentinel Tower in Karrlakton—a hostage for their clan’s good behavior.

With the end of the war, Deneith once again finds itself with a surplus of soldiers. Within the house, the focus has shifted back to the Defender’s Guild. Many of the Blademark Viceroys believe the current peace won’t last, and are thus working hard to keep their best bands together. But many Blademarks have been released from service until circumstances shift.

What Happens Next?

This article is an excerpt. The full version is three times the length of this, and includes the structure of the house, customs, details on the founding families, and focus items tied to the Mark of Sentinel. To access the full article, check out my Patreon!

By many measures, humanity and its cousins may seem to be the weakest of Eberron’s children. Compare me to a simple housecat. My eyes can’t pierce the gloom of night. I have no claws and my teeth are poor weapons. I have no fur to protect me from the cold, and if I fall my bones will break. It may seem that I’m a poor creation next to my little friend. But what I have is the blessing of Balinor — the promise of dominion over all of the beasts of land, sky, and sea. I don’t need the strength of the tribex, because I have the tribex to bear my burdens. I don’t need the wings of a bird when I have a hippogriff to carry me through the air. I wear no crown, but I’m a prince of the wilds.

When people think of the Dragonmarked Houses, the first names that are spoken are usually Lyrandar, Cannith, or Orien. People think of airships with their rings of fire, the lightning rail stretching across the land, House Cannith producing siege staffs and warforged titans. House Vadalis is a quiet house, easily overlooked. And yet, Vadalis is an integral part of life in the Five Nations. Mounts, beasts of burden, agricultural livestock, guardian beasts, pets—all of these are tied to the Handler’s Guild. There are Vadalis heirs who spend their lives producing dairy products or eggs. Of course, most farms and farmers aren’t directly tied to the house. But in the Five Nations, most farms associated with livestock are licensed by Vadalis. The House enforces health standards, provides veterinary care, and breeds and sells the finest stock—including magebred beasts and monstrosities. Vadalis runs the trade schools and offers expert advice. So magebreeding and monstrosities may be the aspects of the house that fire the imagination, but the bulk of the work of the Handlers Guild is comparatively mundane.

As an heir with the Mark of Handling, where others hear barking dogs or singing birds, you can hear intent and emotion. All you have to do is concentrate—taking a few minutes to meditate on your mark—and that noise resolves into meaning. You can speak with any animal, and if you focus through your mark, you can compel obedience. And these are just the simplest gifts of the Mark. While it’s easiest for Vadalis heirs to manipulate beasts, some develop the ability to influence the behavior of any creature, at least momentarily. Others are able to manifest spirits—imagining an animal with such intensity that it briefly becomes real.

All of these things are woven into everyday life in Vadalis communities. If you’re a Vadalis heir, you’ve grown up surrounded by familiars, awakened beasts, and all manner of mundane service animals. Between Dragonmarked heirs and Magewrights, nearly half of the members of the house have the ability to cast Find Familiar. In addition to the many ways in which they can be practical tools, Vadalis heirs use familiars to express their personality, their current mood, and as a fashion accessory. Remember that the form of a familiar can be changed every time the ritual is performed, so familiars can be adapted to match an outfit or used to make a specific statement. If a Vadalis heir has a bright red serpent wrapped around one arm, it means I’m busy, leave me alone; conversely, an Aundairian Silver parrot on your shoulder means I’m in a mood to talk, come say hello! Sparrowmonkeys are often used as assistants, whether Awakened or simply well-trained. Keep in mind that’s sparrowmonkey, not sparrow monkey; it’s the same principle as the owlbear. Vadalis sparrowmonkeys are small winged primates that use the Winged Monkey stat block from Tomb of Annihilation (Small Beast; AC 12, HP 3, 20 ft speed, 20 ft Climbing, 30 ft flight).

Many Vadalis heirs dislike major cities and large crowds of humanoids. Most prefer to be out in the country and around beasts. However, it’s a mistake to think that Vadalis heirs seek to defend the natural world or that they have much in common with druids. Vadalis heirs dislike cities and crowds; but most are quite happy with their ranches and farms. And their powers don’t come from an understanding of Primal mysteries, or any devotion to balance or tradition. The Mark of Handling gives an heir the ability to understand beasts and to control them. Some heirs—notably the Grayswift family—believe in empathy and compassion for the creatures they work with, often going so far as to treat their animal companions as members of their family. But the majority of the heirs of House Vadalis believe that their Mark gives them dominion over the natural world. Beasts are tools to be used for the benefit of the house, and more broadly, humanoid civilization. Many further assert that as a House, Vadalis has the power and the duty to improve upon nature—that what exists is a foundation, but that Vadalis ingenuity will make things better. In creating a Vadalis character, consider if they accept this idea — that Vadalis has the right to bend nature to its will—or if they are more empathetic.

This philosophical divide is complicated by the fact that Family and House are deeply important to Vadalis. Heirs are expected to place the good of the House above all, and the good of kin above anything else. Vadalis heirs know their family trees by heart, and the closer you are in blood, the more loyalty is expected of you. But even beyond direct relatives, all Vadalis heirs are taught to consider any other heir of the house as a cousin, as someone worthy of trust and devotion. Betraying another member of the house is a serious crime and can be cause for excoriation. When another Vadalis is in need, you are expected to offer sympathy at the least, and help when possible. There are limits to what can be expected from this; as a Vadalis heir, you can’t go into a Vadalis stable and demand their best mount. Surely, you don’t need their best mount, and you’d be inflicting financial hardship on them if they just gave it to you. But if you are truly in need—if there is a real emergency, and you have to get to Varna by the end of the day—they might lend you a riding Tribex, or prevail on the local stonespeaker to send a message on your behalf. They will treat you as family, and do what they can to help you. But any such demand and aid is always noted by the House, and you will be marked if you regularly take more than you give; if you receive significant assistance, you may find yourself being called upon to repay that aid with service to the family. So there are sharp divides within the House—the Grayswifts dislike the Lavarans—but they are still kin, and expected to set aside those differences when an heir is in trouble.

The Mark of Handling allows its bearer to understand beasts and to control them. Under the latest version of the rules, anyone who bears the Mark of Handling knows Speak With Animals and Animal Friendship and can cast each of these once per day without using a spell slot. As Speak with Animals is a ritual spell it can be used at will (with a ten minute casting time). The Mark of Handling also gives its bearer the ability to cast Speak With Animals and Animal Friendship on Monstrosities, provided the Monstrosity has an Intelligence of 3 or below. So, a Vadalis heir can befriend a Rust Monster, Basilisk, Carrion Crawler or Bulette as easily as a dog or a tribex.

So at its most basic level, the Mark of Handling allows its bearer to communicate with beasts and to influence their behavior. Animal Friendship is a subtle, long-term effect. But Vadalis heirs can learn to use the Mark of Handling to “handle” creatures more roughly, forcefully shifting thoughts for a short period of time. Command, Confusion, and Hold Monster all reflect a mental demand or disruption, while Beacon of Hope and Calm Emotions are soothing effects. The idea of the Mark of Handling is that it focuses on Beasts (and low-intelligence monstrosities) and most NPC heirs can only cast these spells on such creatures; Calm Emotions is still about calming Beasts, not people. But there’s always been stories about Vadalis heirs being able to using the Mark of Handling to “handle” people—and that’s because some can. An adventurer with the Mark of Handling can use these Spells of the Mark on any creature. Exceptional Vadalis NPCs can as well, although many prefer not to. But there are some within the House who hone this gift even further, learning to cast Charm Person, Charm Monster, Suggestion, or even Dominate Person. Vadalis tradition discourages using the Mark in this way—but there are Handlers out there with this power.

Mental manipulation is one aspect of the Mark of Handling. But the Mark can also grant the bearer the power to conjure animal spirits—to imagine an animal so vividly that it becomes almost real. The simplest form of this is Find Familiar; the heir imagines a creature and dreams it into a temporary reality. Beast Sense is an extension of this. An heir can always see through the eyes of their familiar. When using Beast Sense, they are essentially conjuring a familiar spirit and implanting it within the targeted beast, and that’s the foundation of the sensory link; they are seeing through the spirit they’ve planted within the beast. This is also the principle behind Vadalis Awakening. When a Vadalis heir casts Awaken, they aren’t actually raising the intelligence of the target creature. Instead, they are producing a familiar spirit and giving that spirit control of the target beast; it’s effectively the same as the quori Mind Seed, except that the spirit is a blank slate that doesn’t have the memories or skills of the caster. But the spirit is still a product of the caster’s mind, and Vadalis-awakened creatures often share personality traits or quirks with the person who Awakened them. Conjure Animals is less focused and more forceful, creating a purely spiritual manifestation; this is a relatively rare power of the Lesser Mark, and relatively few heirs can produce it. In my campaign, NPC Vadalis heirs can only use Awaken on Beasts; they cannot Awaken plants. A player character with the Mark of Handling could be an exception to this rule—but Vadalis isn’t known for working with plants.

Kanon versus Canon. Two spells on this list are marked with asterisks, and that’s because they aren’t on the canon Spells of the Mark of Handling list as they will appear in Forge of the Artificer. This is because I’m changing the list for my campaign. The first change is that I’ve replaced the canon spell Aura of Life with Confusion. Aura of Life protects allies from Necrotic damage and restores people with 0 HP to 1 HP. It is a life-affirming healing effect, and in my opinion has nothing in common with the other spells on the list. Even Beacon of Hope is an EMOTIONAL effect rather than a physical one. Thus, I’ve replaced it with Confusion, building on the idea that if you can Command and Calm Emotions, you could disrupt thought and Confuse. Finally, by canon the only 5th level Spell of the Mark is Awaken. My issue with this is that Awaken is an extremely limited spell. It has an eight hour casting time and a 1,000 GP consumable component. It’s not a spell that an adventurer can use all the time, and I feel that makes it a poor choice. Hold Monster is a simple, useful spell for an adventurer that fits the idea of emotional demand—aggressive “handling” disrupting thought. So in my campaign, I’ll offer it as a choice; an heir of the Mark has to decide which of these two talents they possess. And as noted above, in my campaign Vadalis Awaken can’t be used on plants.

By the rules as written, Calm Emotions only works on Humanoids. This is a spell canonically assigned to the Mark of Handling, and this makes little sense if it only works on Humanoids. In the original 3.5 Eberron Campaign Setting the Mark granted access to Calm Animals—but that spell doesn’t exist in 2024. As such, in my campaign I’m adding the following sentence to the Primal Connection trait of the Mark of Handling feat: “You can target Beasts when you cast Calm Emotions.”

Monarchs and Druids. The Spells of the Mark reflect the most common powers granted by the Mark of Handling. These gifts don’t require any sort of Primal connection or Druidic training. Any Vadalis spellcaster—Wizard, Cleric, Sorcerer—can use spell slots to produce these effects, and the Potent Dragonmark feat allows any character to cast them; I generally treat Dragonmarked NPCs as having a form of Potent Dragonmark. However, I’ve also talked about a special sort of Vadalis spellcaster—a Vadalis character who has the powers of a Druid. Within the House, these people are called Monarchs, tied to the idea that the Dragonmark grants them dominion over nature. Vadalis Monarchs have access to Druidic abilities, including Wild Shape and expanded spellcasting; they typically follow the Circle of the Land or Circle of the Moon. However, as with the basic powers of the Dragonmark, these aren’t tied to Druidic devotion and are entirely driven by a powerful connection to the Mark of Handling. While a player character Monarch can cast any spells from the Druid spell list, most Vadalis Monarchs are limited to spells that directly affect animals (Animal Messenger, Locate Animal), that can be depicted as coercion or manipulation (Hold Person, Charm Monster), or which involve transmutation (Polymorph, Enhance Ability, Enlarge/Reduce, healing effects). This talent for transformation is the seed of Vadalis magebreeding. Relatively few heirs are able to master the powers of the Vadalis Monarch, but the seed is there and can be drawn out with focus items. The point of all of this is that House Vadalis has a significant number of heirs with powers that resemble those of Druids, but who have no tie to the Druidic mysteries—and the Ashbound in particular despise Vadalis Monarchs. With that said, there ARE Vadalis heirs who do embrace Druidic traditions, most often tied to the Grayswift family.

Vadalis heirs use Channeling Rods, Dragonmark Channels, and Dragonmark Reservoirs, and they’ve crafted unique items like the Collar of the Wild Bond to enhance the powers of the Mark. But they’ve also developed focus items and Eldritch Machines that are crucial to the business of the house but which have little application for adventurers. Balinor’s Blessing is one example of this; they are used at Vadalis ranches to enhance the health and virility of livestock. Other items ease the process of childbirth, help with long-term animal training and domestication, or play a crucial role in the process of Magebreeding. The Mark alone doesn’t grant spells related to Magebreeding; it’s through focus items and rituals that Vadalis heirs are able to produce these effects.

Balinor’s Blessing

Eldritch Machine (requires attunement by a creature with the Mark of Handling)

This six-foot stone pillar is engraved with the patterns of the Mark of Handling. As long as a creature with the Mark of Handling is attuned to the pillar—a process that must be repeated every day—It has the following effects within a 2000 foot radius.

Collar of the Wild Bond

Wondrous Item, varies

If you possess the Mark of Handling, you may use a Magic Action to cast Dominate Beast on a Beast you can see that’s wearing a Collar of the Wild Bond. This doesn’t use a spell slot, but the other limitations of the spell apply. The effect has a range of 60 feet, and the creature can negate the effect with a successful Wisdom saving throw; your spellcasting ability for this effect is the same one you chose for the Mark of Handling. You must concentrate to maintain the effect, but as long as you are within 200 feet of the creature, you can maintain the spell indefinitely.

There are two forms of Collar of the Wild Bond. The Uncommon Collar only works on Beasts. The Rare version of the Collar can be used on Monstrosities with an Intelligence of 3 or less.

Scepter of Wild Dominion

Rod, Rare (requires attunement by a creature with the Mark of Handling)

While holding this rod, you have the following benefits.

When most people hear “Vadalis,” they think of magebreeding. This is a term that has many meanings. Let’s start with the earliest description.

The widespread use of magic on Eberron has led to the development of magical enhancements to animal breeding, particularly within House Vadalis. Some experiments in that direction have created new creatures that are actually magical beasts, with unusual intelligence and supernatural or spell-like abilities. In general, however, the aim of these breeding programs is simply to create better animals—ones that are more suited for use in the work of daily life. These magically enhanced animals are called magebred.

Today, House Vadalis identifies three distinct forms of magebreeding.

Incremental magebreeding is similar to breeders in our world trying to produce a new breed of dog. The result is a slight variation in the standard beast well suited toward a particular role: a hen that lays larger eggs, a tiger that’s easier to train, a hound that thrives in colder climates or has a remarkable sense of smell. One concrete example of this is the Riding Tribex (seen in Frontiers of Eberron: Quickstone). For thousands of years, the Plains Tribex has been bred as a beast of burden and source of food. The Riding Tribex is smaller and faster—sturdier than a horse and capable of enduring long, sustained trips.

Enhanced magebreeding seeks to strengthen a creature, imbuing it with minor supernatural qualities. The Magebred Animal template in the 3.5 Eberron Campaign Setting suggests the following changes:

These creatures are still considered beasts; in 3.5 D&D terms, they were limited to an Intelligence of 2. A few critical points about this template. It’s intended to reflect BREEDS of magebred animals. So Redleaf hounds all have +4 Dexterity and a bonus to tracking; it’s not as though two pups in the same litter each get to choose whether the +4 goes to Strength or Dexterity, or whether they get the boost to movement or tracking. House Vadalis created the first Redleaf hounds through active enhanced magebreeding; but ever since then, Redleaf Harriers have bred that enhanced line, while the innovative magebreeders have moved on to other things.

The second point is that this is a simple template that is intended to give a broad example of what can be done. The template only suggests a possible bonus to movement, armor class, or tracking checks. But I could see any of the following as being the sort of features that enhanced magebreeding could produce:

The key points here are that the general goal of enhanced magebreeding is to produce new breeds with hereditary traits and generally requires generations to produce results. They don’t take an existing horse and give it metallic fur; they easily COULD with cosmetic transmutation, but it wouldn’t last. Instead they work to instill a trait over multiple generations, that will thereafter be passed down to offspring. Typically enhanced breeds are only available to bound businesses in the Handler’s Guild, and enhanced beasts are sterilized before they are sold to others. Stories say that there are all sorts of safeguards to deal with poachers—that enhanced animals will die if they aren’t fed special Vadalis supplements, that they will frenzy and turn on rustlers, that Vadalis has death squads that sneak around the world hunting for unauthorized breeders—but these are probably just rumors. Probably.

Innovative magebreeding involves the creation of either an entirely new species or imbuing an existing creature with dramatic supernatural characteristics. Popular legend holds that the house’s first act of innovative magebreeding was the production of the hippogriff; skeptics claim that Vadalis simply discovered the first hippogriff after it emerged from a manifest zone tied to Kythri. A more recent and dramatic example is the Tressym, first produced just twenty-four years ago. The house is always working on innovative projects, but actual successes are far and few between; innovative creations are often sterile, stillborn, or mentally unstable. Many innovative creatures are Monstrosities as opposed to Beasts.

While it’s more colorful and exciting than, say, dairy farming, magebreeding is a tiny fraction of the work of House Vadalis. Ranches and kennels tied to the Handler’s Guild may perform iterative magebreeding, but enhanced and innovative magebreeding is performed almost entirely within house enclaves or in conjunction with the Twelve. The Tressym was produced through collaboration with House Medani, and there are stories of Vadalis working with House Jorasco on ghastly experiments involving troll’s blood and medusa’s eyes.

So what does a magebreeding facility actually look like? What is the daily work that goes on within? The following tools are used in magebreeding.

So the point is that magebreeding facilities often look like farms or veterinary hospitals, with special chambers for performing rituals or imbuing planar energies. But magebreeding is invariably a long-term process, involving both breeding and the careful study of multiple generations. Vadalis is always searching for ways to produce swifter and more dramatic results… And these efforts often end in disaster, or at least adventure!

This is an excerpt. The full article is three times as long, and explores the history, structure, and families of House Vadalis. To get access to the full article, check out my Patreon!

The crystal shows love Lyrandar. How many times have we seen a dashing Lyrandar captain facing off against pirates, dancing on the wind, landing blows with their rapier and rapier wit? That’s the story we’re sold—they’re daring, they’re bold. The House wants us to like them, to admire their adventurous spirit, to trust they’ll take us where we want to go. But just you look at the seal of the Windwright’s guild. You see the ship, riding the water or the wind. But around it and below it lies the Kraken, its tentacles reaching out to seize the world. Lyrandar has always been driven by ambition. They began with their feet caked in river mud, and now they’ve laid claim to the sky. I know, I know. You think I spend too much time reading the Voice of Aundair. But I tell you this: the sky won’t be enough for House Lyrandar.

There’s a storm inside of you. It was born when you first manifested your dragonmark, and it’s whirled within you ever since. Sometimes you want to move like the wind, to dance across the hall or dart through the rigging of a ship. Sometimes you want to let it out—to unleash your tension with a single clap of thunder, or to let it pour out of you in a massive gust of wind. There’s a storm inside of you, but only you know what it feels like. Is it cold and wet, full of ice and sleet, relentless hail that will wear down your foes? Or does the wind inside of you lift people up, catching you when you fall and shielding you from harm? What is the storm inside of you, and how do you reveal it to the world?

The Mark of Storms has gone through many changes over the editions. This article considers it in its latest incarnation, as it was presented in Unearthed Arcana and will appear in Forge of the Artificer. If you have the Mark of Storm, you have an intuitive bonus to Acrobatics and navigation. You have resistance to Lightning Damage. You know Gust of Wind and can cast it once per day without expending a spell slot… and you can cast the Thunderclap cantrip at will. These gifts are far more dangerous than the powers of most other Dragonmarks. A Cannith can mend, a Sivis can send messages, a Phiarlan can weave illusions. But your mark can flow out of you with explosive force. Every Lyrandar enclave has a fortified storm suite, where heirs are kept in isolation after manifesting the mark until they learn to control it; though an heir can go to the storm suite at any time if they just want to unleash their power without restraint, with no risk of hurting anyone. Due to this intensive training, Lyrandar heirs are very aware of their personal space—a Thunderclap strikes everyone within five feet. A trained heir runs no risk of accidentally unleashing their power, but releasing a Thunderclap is an exhilarating feeling and many will do it to accentuate a dramatic point to to express joy or anger; but again, they are careful to know when such an act could put innocents at risk.

House Lyrandar has always been driven by pride and ambition. A Lyrandar captain is the monarch of their own tiny kingdom, and considers themself to be the equal of any king or queen. From childhood, Lyrandar heirs are encouraged to dream big and to believe in their own potential. If you’re making a character who bears the Mark of Storm, consider how its power affects them. Do they love wild motion and dramatic displays? Or are they more akin to still water with hidden depths?

The spells of the Mark of Storm follow two paths. Feather Fall, Levitate, and Wind Wall are tied to the wind, while Fog Cloud, Sleet Storm, and Control Water are tied to water. While some exceptional heirs (including any player character) can draw on all of these powers, most Lyrandar heirs have an affinity for one or the other; thus, a typical Lyrandar NPC might be able to cast Feather Fall or Sleet Storm, but probably not both of them. The ability to conjure elementals is common to both paths, but heirs are usually only able to conjure the type of elemental associated with their affinity (Air or Water). Shatter is a focused form of Thunderclap and it’s something any Lyrandar heir can master with effort, but many don’t bother to do so; it requires an aggressive outlook, and heirs pursuing a peaceful life may not want to wield such power.

Conjuring Elementals. Where did the idea for the Elemental Galleon come from? Why was it associated with Lyrandar to begin with, if Lyrandar don’t bind elementals? The answer is that the heirs of House Lyrandar have been using elementals since the Mark of Storm first appeared—just in a far less efficient manner. The Lesser Mark of Storm allows the bearer to cast Conjure Minor Elementals. The Greater Mark gives access to Conjure Elemental. Lyrandar heirs quickly learned how to use air elementals to fill their sails and water elementals to propel larger vessels. However, doing this directly is a considerable effort for the heir manifesting the elemental and it lacks precision. The invention of the Elemental Galleon demonstrates the purpose of the Twelve: to combine the expertise of the Dragonmarked Houses to create things no house could create on its own. The first galleons still relied on a Lyrandar heir to produce the elemental, but channeled that spirit into ship systems—creating the iconic elemental ring. By working with the Zil, the Twelve made the breakthrough that led to the modern elemental vehicles—summoning an independent elemental that could be bound to the ship itself. Because the point is that when a Lyrandar heir conjures an elemental, it’s not coming from Lamannia.

When you conjure an elemental you’re drawing out the storm that lies within you; it is your spirit made manifest. Bear in mind that (under 2024 rules) when a Lyrandar heir conjures an elemental, it’s not an independent, sentient entity. Conjure Minor Elementals creates an emanation that radiates out from the heir, a storm that enhances their attacks. Conjure Elemental summons a “Large, intangible spirit” that doesn’t move once cast—a swirling storm core. It’s a manifestation of elemental power, not an independent entity. The key point is that the 2024 rules as written only describe the combat effects of these spells; but Lyrandar has developed focus items that can harness that elemental power to use it as motive force. It’s further the case that even though Lyrandar heirs don’t summon independent elementals, an heir’s relationship with their inner storm gives them an affinity for interacting with elemental forces… which is enhanced by the Wheel of Wind and Water, and which in turn is why airships currently rely on Lyrandar pilots for reliable control of the elementals.

Purely by the rules, someone who casts Conjure Elemental or Conjure Minor Elementals can draw on any elemental. Lyrandar NPCs should be limited to Air or Water. If a Dragonmarked player character is conjuring an elemental through the Mark, they should also be limited in this way. If they are a spellcaster using a spell slot to cast the spell, then they can call on any element; they may be guided by their Mark, but they are drawing on additional magic in casting the spell.

Storm Sorcerers and Lyrandar NPCs. Lyrandar NPCs are generally presumed to have a form of the Potent Dragonmark feat, granting them a single spell slot for each tier of their Dragonmark—Least (1st or 2nd level), Lesser (3rd or 4th level), and Greater (5th level). A typical heir is limited to either Wind or Water spells. Player characters with spellcasting ability have access to all of the Spells of the Mark and can use spell slots to cast those spells. Exceptional Lyrandar NPCs (including agents of the Hurricane Harvest) can have this same level of power, with the ability to cast all of the Spells of the Mark and to do so more than once per day per tier. Beyond this, Lyrandar spellcasters can choose to ascribe some or all of their spellcasting abilities to their Dragonmark. A Lyrandar Storm Sorcerer is an obvious candidate for this, but a Fathomless Warlock could say that their “patron” is their Mark itself. Under such circumstances, a DM could slightly reflavor existing spells to better fit the idea that they are tied to the dragonmark. For example, Lyran’s Shield is identical to Armor of Agathys, but inflicts Lightning damage instead of Cold damage. Storm of Selavash is a Fireball that inflicts Lightning Damage. The Aegis of the Firstborn is Fire Shield, but with the choice of Wind (inflicting and granting resistance to Lightning Damage) or Water (inflicting and granting resistance to Cold Damage).

Controlling the Weather. In the original 3.5 Eberron Campaign Setting, the Greater Mark of Making gave the bearer the power to cast Control Weather. The idea that Lyrandar had this ability was an important part of the house’s identity; the Raincaller’s Guild is a major part of its business. However, later editions balked at this, with Rising—and now, Forge of the Artificer—granting Conjure Elemental in place of Control Weather. From a design perspective, there’s two solid reasons for this. In Fifth Edition, Control Weather is an 8th level spell. The 3.5 ECS didn’t care that the Mark of Storms had access to a spell higher level than that of most Greater Dragonmarks. But the “Spells of the Mark” approach to Dragonmark powers doesn’t support giving a character access to an 8th level spell. And there’s a second important reason: Control Weather isn’t that useful to a typical adventurer. In either of its 5E forms, Conjure Elemental is a spell with clear value in an encounter. Control Weather is a highly situational spell that has a lot of flavor and story potential—but which is likely to be useless in a typical dungeon crawl. So I understand the rationale behind this switch. Nonetheless, the lore of House Lyrandar is based on the idea that they can control the weather. Rising From The Last War sought to bridge this by introducing the Storm Spires: Eldritch machines that allow Lyrandar heirs to control the weather around the Spire. I think the Storm Spire is great: in my campaign, a Storm Spire amplifies and expands the power of the mark, controlling weather over a wider area and for an indefinite duration. It’s an excellent tool for a large community with an established Lyrandar presence. But I still want the traveling Raincaller who can come to your farm during a drought and turn things around. With this in mind, in my campaign I’m implementing the idea that controlling the weather is a specialization within the house. Some heirs learn to externalize the storm they hold within; if they develop the Greater Dragonmark, they have the ability to cast Conjure Elemental. Others—those that emulate the still water with hidden depths—learn to manipulate the storms around them rather than to unleash the storm within. Those that follow this path replace Conjure Elemental on the Spells of the Mark list with Control Weather. They are able to cast Control Weather once using a 5th level spell slot, and regain the ability to do so after they complete a long rest; otherwise, they can cast it using an 8th level spell slot. So, Raincaller NPCs with the Greater Mark of Storm can control the weather; if a Lyrandar adventurer wants this power, it comes at the expense of Conjure Elemental.

Lyrandar heirs regularly employ the focus items described in Exploring Eberron—Dragonmark Channels and Reservoirs. Exploring Eberron mentions Storm’s Embrace, a focus item that duplicates the Ring of Feather Falling. In general, any item that deals with wind or water can be reframed as a Lyrandar focus item. Here’s a few additional focus items. The Hurricane Cloak is beloved by Lyrandar swashbucklers. The Windwright’s Anchor and Raincaller’s Crown are tools used by members of the Lyrandar guilds. The Windwright’s Anchor is a key tool for Lyrandar riverboat captains, who fill their sails with Gust of Wind, while the Raincaller’s Crown allows a wandering Raincaller to maintain a shift in the weather for a full day—and to go indoors after casting the spell. Scepters of the Firstborn are rare weapons treasured by champions of the Hurricane Harvest.

Hurricane Cloak

Wondrous Item, uncommon (requires attunement by a creature with the Mark of Storm)

While wearing this cloak, you can take a bonus action to make it billow dramatically for one minute. You can take a Magic action to catch the wind within the cloak, lifting you just off the ground. While the cloak remains active, you have a Fly speed of 40 feet and can hover. You must maintain concentration to sustain this flight, as if you were concentrating on a spell. The cloak keeps you aloft until you end your concentration.

Windwright’s Anchor

Wondrous Item, uncommon (requires attunement by a creature with the Mark of Storm)

This amulet enhances the powers of the Mark of Storm. When you cast Gust of Wind, Fog Cloud, Wind Wall or Conjure Elemental, you can use the Anchor to enhance the duration of the spell. This requires intense focus and ongoing concentration. While using the Anchor in this way, you are Restrained. In addition, you must use an action on each of your turns to maintain the effect. As long as you do so, you can maintain the spell effect indefinitely.

Raincaller’s Crown

Wondrous Item, uncommon (requires attunement by a creature with the Mark of Storm)

When you cast Control Weather, you can maintain concentration on the spell for up to 24 hours. You must be outdoors to cast the spell, but it doesn’t end early if you go indoors after casting it. When you end concentration, the weather you have created continues for eight hours before fading.

Scepter of the Firstborn

Rod, Rare (requires attunement by a creature with the Mark of Storm)

This rod has 7 charges and can be wielded as a mace.

Mighty Thunder. If you cast Thunderclap while holding the Scepter, the damage is increased by 1d6 and the saving throw DC is increased by 2.

Storm Unleashed. While holding the Sc epter, you can expend up to 3 charges to cast Lightning Bolt (Save DC 15) from it. For 1 charge, you cast the level 3 version of the spell. You can increase the spell’s level by 1 for each additional charge you expend.

Regaining Charges. The Scepter regains 1d6+1 expended charges daily at dawn.

This is a preview of the full article available to patrons. The full article is four times the length of this one, and includes information on this history, structure, family, and customs of House Lyrandar. If you’d like to read the full thing—and to help support my creating more of these articles—check out my Patreon here!

I’m currently working on articles about House Lyrandar for my Patreon, but having just talked about funerary customs in the previous article it feels like a good time for a flashback to this article, which I originally wrote in 2017!

Whether you’re seeking your fortune in the depths of a dungeon or trying to save the world from a dire threat, many roleplaying games incorporate an inherent threat of death. Whether you run out of hit points or fail a saving throw, any adventure could be your last. As a gamemaster, this raises a host of questions.

One question that’s worth asking from the onset: Is death necessary? Do you actually need player characters to die in your campaign? Roleplaying games are a form of collaborative storytelling. We’re making the novel we’d like to read, or the movie we want to watch. Do you actually need to the threat of permanent death in the game? Removing death doesn’t remove the threat of severe consequences for failure. Even in a system that uses hit points, you could still have something else happen when a character reaches zero hit points. Consider a few alternatives.

The point to me is that these sorts of effects can make defeat feel interesting – MORE interesting than death and resurrection. In one of my favorite D&D campaigns, my party was wiped out by vampires. The DM ultimately decided that a wandering cleric found us and resurrected us, and essentially erased the incident from the record. I hated this, because there was no story; we had this brutal fight, we lost, and then nothing happened. I argued that we should have our characters return as vampire spawn, forced to serve the Emerald Claw until we could find a way to break the curse. It would have COMPLETELY changed the arc of the campaign, to be sure. But it would make our defeat part of the story and make it interesting – giving us a new goal. And when we finally DID break the curse and find a way to return to true life, it would feel like an epic victory.

Generally speaking, even if I’m using another consequence for death, I will generally keep it that a character falls unconscious when “dead” – it may not be permanent, but they are out of the scene. However, even that could depend on the scene. Taking the idea of the village attack where “death” means an important element of the village is lost, I might say from the outset that any time a player drops to zero hit points something major is lost to the attack… and that the player will immediately regain 10 hit points. This is not a scene where the players can die unless the entire village is wiped out first; the question is how much of the village will be left when the battle is done. But it’s important that the characters understand these consequences from the start of the battle; you can’t build suspense if the players don’t know the consequences.

All of this comes back to that question should I fudge the dice to avoid a player dying a lame death? If death is truly the end of the story, it IS lame to lose your character to a random crappy saving throw or a wandering monster that scored a critical hit. But if you don’t have death in the game, and players know that, you don’t HAVE to avoid that death – you can just scale the consequences of the “death” to fit the circumstances. If it truly is a trivial thing, then have a trivial scar or minor misfortune as the consequence – the character literally has a minor scar to remember it by, and they’re back on their feet. And in my experience, scars and misfortune can actually generate more suspense than simple death. Character death is binary. It’s boring. You’re dead or you’re not. But the potential for loss or a lingering scar – you never know what you might be about to lose when you drop to zero HP, and that’s much more disturbing.

2025 Update—DAGGERHEART. I wrote this article in 2017 with D&D in mind, but here in 2025 the RPG Daggerheart has an interesting approach as part of its core rules. In Daggerheart, when a character loses their last hit point, they choose a Death Move. This can be Blaze of Glory, allowing the character to take one action that critically succeeds before they die; to Avoid Death, falling unconscious and potentially gaining a scar much as I suggest above; or Risk it All, giving them a chance to roll the dice and either regain some hit points or drop dead. I love that this gives the choice to the player: that they can design to survive but with a scar, or instead to go out accomplishing something memorable… and it’s a system that could easily be adapted to D&D.

The critical thing about the idea of misfortune or scars is that the character needs to have something to lose. They need to care about SOMETHING beyond themselves – something that can be threatened by misfortune. If your campaign is based in a single location, it could be about the place: a favorite bar, a beloved NPC. It could be something useful you have given to them, whether it’s a useful object or a powerful ally or patron. It could be something the player has created themselves: family, a loved one, a reputation that’s important to them. Following the principle that this isn’t about punishment but rather about driving an interesting story, misfortune that results in loss of character ability could be temporary. Take the earlier example of the paladin’s holy avenger expending its energy to save him; this isn’t simply punishment, it’s now the drive for a new branch of the story.

In Phoenix: Dawn Command this is actually part of character creation. In making your character you need to answer a number of questions. As a Phoenix, you’re someone who died and returned to life. What gave you the strength to fight your way back from the darkness? Who are you fighting for? What do you still care about? And what are you afraid of? All of these things are hooks that give me as the gamemaster things that I can threaten to generate suspense. But you can ask these sorts of questions in any campaign.

Now, sometimes players will have a negative reaction to this: I’m not giving you something you can use against me! The critical thing to establish here is that it’s not aboutusing things against them. As a GM you and the players aren’t enemies; you’re partners. You’re all making a story together, and you’re asking them if I want to generate suspense, what can I threaten? You’re giving them a chance to shape the story – to decide what’s important to their character and what they’d fight to protect. I don’t want to read a story about a set of numbers; I want to read a story about a character who has ties to the world, who cares about something and who could lose something.

This ties to a second important point: failure can make a compelling story. Take Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark. His defeat within the first ten minutes of the film creates tension that builds to the final resolution. Inigo Montaya’s story in The Princess Bride begins with defeat and is driven by his quest to avenge that loss. This is why I wanted to become a vampire spawn in the example I gave above – because embracing that defeat and following the story it created would be more interesting than simply being resurrected and continuing as though nothing happened.

Which brings us to the next topic…

In many D&D settings, resurrection is a reliable service available to anyone who can pay a price. This also becomes the case once the party has a caster who can perform the ritual. I hate resurrection without consequence. I’d rather have a character not die at all than have them just casually return to life with no story attached to it. The original Eberron Campaign Setting includes the Altar of Resurrection, a focus item that lets a Jorasco heir raise the dead (and it’s specifically resurrection, not just the more limited raise dead). Confession time: I hate that altar. I didn’t create it, and in many subsequent sourcebooks (Sharn, Stormreach) I pushed explanations for why it wasn’t a reliable service. Essentially, resurrection is a useful tool for player characters if you’re running a system where death can easily and casually happen. But not only is it a boring way to resolve a loss, it’s something that should have a tremendous impact on a society – and Eberron as it stands doesn’t account for that impact. If Jorasco can reliably resurrect, then they hold the keys to life and death. They’d presumably offer insurance policies, where nobles and the wealthy (criminal masterminds, members of the Aurum) can be assured of resurrection should they unexpectedly die. And someone else holds those keys as well… because resurrection, even via altar, specifically requires diamonds. So whichever nation is sitting on the largest diamond reserves suddenly has a new source of power and influence. Beyond this, casual resurrection kills a lot of stories. Murder mysteries aren’t as compelling if it’s just a matter of shelling out 10K GP to get the victim back on their feet. It’s hard to explain the death of a noble by any means other than old age. The Last War began when King Jarot died – so, why wasn’t he resurrected?

There’s lots of ways to explain this without removing resurrection.

But even with all that, I don’t like casual, reliable resurrection. I don’t feel a need to remove the spell from the game, but I always establish that resurrection only works if the character has an unfulfilled destiny. Essentially, resurrection generally only works for player characters or recurring villains. In the sourcebooks I mentioned, I emphasized that most religions don’t encourage use of the spell: the Sovereigns have called you to their bosom or your soul is joining the Flame, and that’s what’s supposed to happen. I also presented the idea that Jorasco resurrection can have unexpected consequences – Marut inevitables trashing the Jorasco enclave, ghosts coming back with (or instead of) the intended spirit – and that Jorasco adepts will perform an augury ahead of time to determine if resurrection is in fact possible. So I didn’t REMOVE it from Eberron – but I’ve suggested a lot of ways to limit it. With that said…

Making Resurrection More Interesting

If you’re dead-set (get it?) on using death and resurrection, one option is to make it interesting. Resurrection is never free – and I’m not just talking about a pile of diamonds. Consider the following:

A critical point here: you could use either of these options with or without a resurrection spell. Taking the first option, you can say that a cleric casting a resurrection spell doesn’t AUTOMATICALLY return the character to life; rather it’s the casting of that spell that has allowed the bargain to occur. If the player turns down the bargain, the spell will simply fail. Alternately, you can say that this bargain is offered independently of any magic, which is a good option for low-level characters. Everyone THINKS the character is dead… and then suddenly they pop back up, with a new mission!

You can also find a path between the two, and the best example of this is Thoros of Myr and Beric Dondarion in Game of Thrones. When Beric dies, Thoros can resurrect him. But generally speaking, Thoros doesn’t have the powers of a high-level priest; nor is it implied that he can resurrect just anyone. But he can resurrect Beric, which seems to be evidence that Beric has some sort of destiny to fulfill. You can easily say that the party’s first-level cleric discovers that he can resurrect the party fighter. But again, the question now becomes why he can resurrect the fighter. Will this work forever? Can he resurrect other members of the party? Or is it only temporary until the fighter achieves some specific goal, and then he’ll die once and for all? And is there another price being paid – every time the cleric performs a resurrection, is someone innocent dying to take their place? There’s a lot of ways to make this a compelling part of your story, and not just consequence-free failure.

You don’t want to try any of this crazy stuff. You want old-fashioned, classic death. And you’ve had a PC die. How do you bring a new character in without it feeling utterly bizarre that the group just gels around this stranger? Here’s a few quick thoughts.

That’s all I have for now, but post your thoughts on death and resurrection and what you’ve done in your games!

Every month I answer interesting questions posed by my Patrons. Questions like…

It’s a good question. Sacred Flame and Toll The Dead will both kill you; why is one seen as “good” and the other as “evil”? Keep in mind that the practice of necromancy isn’t illegal in the Five Nations; even animating corpses is legal, as long as you have a legitimate claim to the corpse. But it’s still a path that’s largely shunned and those who practice it are often presumed to be evil. Why is that? There’s a few reasons.

Undead are a real, everyday threat. Always remember that Eberron is not our world. It is a world in which predatory undead are a concrete threat that can manifest at any time. Ghouls can spontaneously manifest in graveyards. Shadows can potentially appear in any unlit area, and they’re drawn to negative emotions—especially during the nights of Long Shadows, which is why everyone gathers around the light on those nights. Skeletons and zombies can spontaneously animate in Mabaran zones or when Mabar is conterminous, and when they do, they are predatory creatures that seek to slay the living. So any time people see an animated skeleton, there is an instinctive reaction beyond just the natural that’s a dead thing and it shouldn’t be moving—it’s that you’ve grown up KNOWING that the restless dead want to kill you.

#NotAllNecromancy. There are a number of Necromancy spells that are part of everyday life in the Five Nations. Spare The Dying and Gentle Repose are basic tools used by healers and morticians. No one’s complaining about Revivify or Raise Dead. Speak With Dead is employed by mediums and archaeologists alike. There are other spells in the school that most people don’t even know are necromancy. The common person on the street would likely say “Wait, so Poison Spray is Necromancy, but Acid Splash is Evocation? Who labels these things? With this in mind, a basic point is that appearance matters. If your False Life just looks like a green shield, it’s no different from Mage Armor. But if it’s a whirling shroud of whispering ghosts, or if it causes you yourself to take on a zombie-like appearance, that’s going to upset people. Same with Toll The Dead. If it’s a green bolt that kills people, no biggie. If it’s a bolt of howling shadows that causes flesh to decay, people will be upset. Because…

The problem is Mabar. Necromancy spells draw on different sources of energy. Spells that channel negative energy—pretty much any spell that inflicts necrotic damage or animates negatively-charged undead—draw on the power of Mabar. Spells that draw on positive energy and sustain or restore life—Raise Dead, Spare The Dying—are usually drawing on Irian. And spells that interact with the dead in a neutral way, such as Speak With Dead, typically draw on Dolurrh. People don’t have an issue with Irian, and Dolurrh is spooky, but it’s something that’s waiting for you when you die; it’s not going to come get you. Mabar actively consumes light and life. People know this. They know that crops wither in Mabaran manifest zones. They know deadly shadows and hungry dead rise when Mabar is coterminous. Here again, people have had it drilled into them that Mabar is dangerous—and as a result, any sort of magic that is perceived to have a connection to Mabar can trigger a you’re messing with powers better left alone reaction.

Not everyone agrees. For the reasons given above, most people want nothing to do with Mabaran necromancy. The Undying Court and Silver Flame argue that any invocation of Mabaran energy eats away at the life force of Eberron, and that it’s essentially damaging the environment; even if you aren’t doing something evil with the spell, you’re causing long term harm to get the effect. But the Seekers of the Divinity Within say that the reverse is true—that by channeling existing Mabaran energy into spells, they are actually drawing it OUT of the environment. The Seekers likewise dismiss fear of animating skeletons and zombies because of their deadly counterparts as the equivalent of refusing to use fire in a hearth because wildfires are destructive, or refusing to explore electricity because someone was once struck by lightning. The power of Mabar may be dangerous when it manifests spontaneously, but that’s all the more reason to understand it and to learn to use it safely. These are the principles that led Karrnath to embrace wide-scale necromancy during the Last War, and why undead are still used in many ways in Seeker communities—such as the city of Atur.

There’s no absolute answer here, and if Mabaran magic IS damaging the environment it’s doing it very very slowly. But these reasons are why public opinion is against the most dramatic forms of necromancy in much of the Five Nations—because the power behind it is seen as dangerous and fundamentally evil.

Who cares about corpses? The Church of the Silver Flame practices cremation, precisely to minimize the risk of spontaneous undead. Seekers of the Divinity Within believe that death is annihilation and that nothing important remains with the corpse; they have no sentimental attachment to corpses and feel that it’s practical and sensible to use them for undead labor. But the Five Nations have graveyards, crypts and mausoleums. Sharn: City of Towers describes the City of the Dead, a massive necropolis adjacent to the City of Towers. This is the work of the Vassals. The Pyrinean Creed maintains that the spirits of the dead pass through Dolurrh on their way to the higher realm of the Sovereigns. They believe that the corpse serves as an anchor for the soul; that while the soul may no longer reside within it, it steadies it on its journey. The destruction of a corpse doesn’t doom the soul, but it makes its journeys difficult. Thus, Vassals bury their dead and maintain cemeteries and crypts. The Restful Watch is a sacred order that performs funerals and watch over graveyards. This ties to the fact that Raise Dead requires an intact corpse; while it’s RARE, Vassal myth includes the idea that heroes may be called back to service after death. now, WE know that Resurrection can bring people back from ashes… but remember that in the Five Nations, wide magic tops out at 5th level. People know Raise Dead is possible; raising someone from ashes is the stuff of legends. Add to this the fact that once a corpse has been made undead, it can’t be restored with Raise Dead. With this in mind, this is another reason Vassals have a instinctive revulsion to animating the dead. While it’s legal as long as someone has a valid claim to a corpse, Vassals consider it a violation. And in the instances where Karrnath animated the corpses of fallen enemies during the Last War, Vassals saw it as a horrifying act.

And if you needed just a little more… The overlord Katashka is an overlord that embodies the horrors of both death and undeath. The cults of Katashka want people to be afraid of the restless dead; throughout history, they’ve unleashed countless undead terrors precisely TO sow fear.

That’s all for now. Thanks to my Patreon supporters for making these articles possible! This month, Patrons received a giant article on House Medani, as well as being able to participate in two live (and recorded) Q&A sessions. If that sounds like a good time, check it out!

You’ve heard of the Basilisk’s Gaze, then? Medani operatives, charged under the Treaty of Thronehold to hunt down the worst war criminals of the last century. It’s kind of odd, right? If you want to FIND someone, you go to Tharashk. Why Medani? Well, it could be that Breland objected to Tharashk because of their close ties to Droaam. But you know what I think? I think it’s because these people the Gaze is hunting, they aren’t common criminals. They’ve got money, influence, magic. These people can shield themselves from divination, establish new identities. Finding a person like that, it’s more of a puzzle than a job for a simple bounty hunter. And apprehending them… that’s a thing that would have to be done quietly and carefully. You’d have to be able to anticipate their routine, know where they’d start their day. Know their favorite strain of tal. Have a paralytic poison on hand, slow-acting but undetectable, and have sufficient charm to keep them talking until the poison takes effect. What do you think? Hmm? Can’t respond? Don’t worry. My friends and I will help you out. You’ve got a tribunal waiting for you at Thronehold, Viktor ir’Cazin.