And on the pedestal these words appear: ‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away.

Percy Shelley, “Ozymandias”

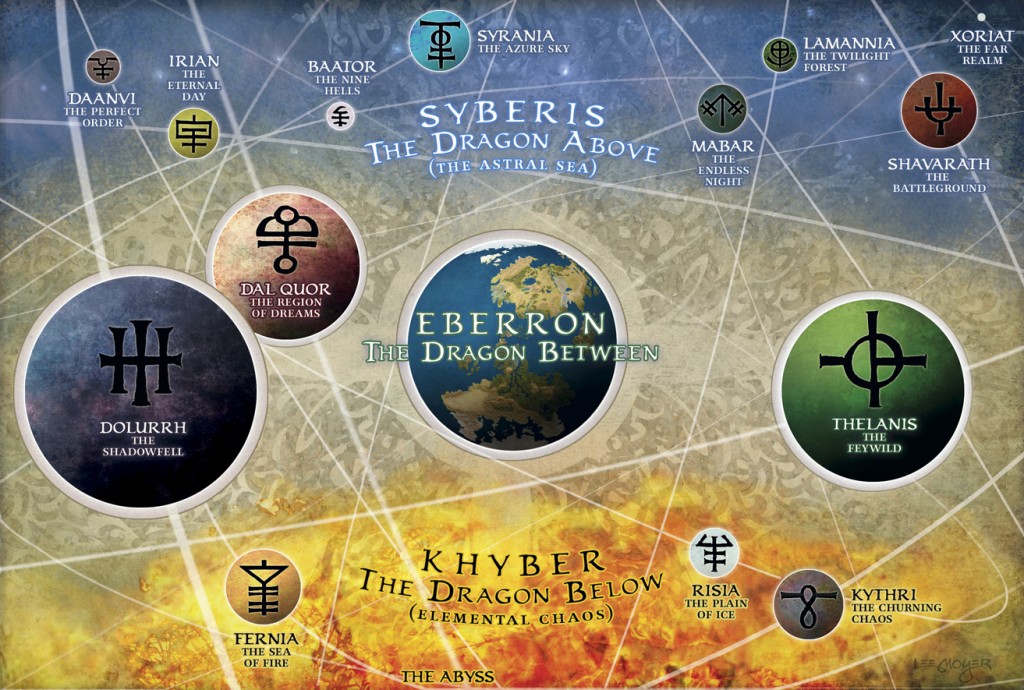

A sea of liquid shadows laps against black sands and basalt cliffs. A skull lies half-buried in the sand, empty sockets gazing into the roiling mist. The bone isn’t sun-bleached, for there is no sun here; only a faint glimmer from the deep violet moon that hangs in the sky. If you’re playing in Eberron, this is the plane of Mabar. If you’re playing Phoenix: Dawn Command it could be a realm of the Fallen in the deep Dusk. For now, set aside specific system and setting and consider the Endless Night.

Those who know little of what lies beyond common reality often assume that the Endless Night is the plane of “darkness” — that this physical trait is its defining concept. Though the plane is shrouded in shadows, this eternal gloom is just a symptom of the true nature of this place. Even the brightest day will eventually end in darkness, and the Endless Night embodies this idea. It is the shadow that surrounds every island of light, patiently waiting to consume it. This isn’t the place where the souls of the living go after death, but it is the plane of death itself — the hungry shadow that consumes both light and life. It is entropy, hunger and loss — embodying the idea that all things will eventually end in darkness.

ENVIRONS

Like many of the planes, the Endless Night isn’t one contiguous landscape. Rather, it’s layers of reality, each one a different vision of desolation and inevitable decay. In one layer a desert of black sand is broken by jagged obsidian peaks. In another layer, a once-fertile valley has wasted away; crumbling farms are scattered amid withered fields. Another layer is a single vast city. The fountains are dry, the walls are cracked, but rotting tapestries and chipped mosaics speak of an age of wonders. The critical thing to understand is that this cities has ALWAYS been a ruin. This is what Mabar is: the end of things embodied. When mortals pass through, the idea of decay may manifest dramatically – a bridge collapses, a floor gives way – but come back in a week and there will be a new crumbling bridge ready to fall. These layers are symbols of inevitable entropy and lost glory; the precise details may evolve and change, but the net effect remains the same.

While the stage varies — a desert, a ruined city, the withered remains of fertile farmland, or anything else you can imagine — the story is always about loss, entropy, despair, and death. Feel free to add anything that ties to these themes. A massive battlefield filled with the intertwined bones of dragons and giants. Ossuaries and catacombs. Crumbling memorials, with names just too faded to read. Barren orchards and dried riverbeds. And tombs… from tiny unmarked crypts to the death-palaces of fallen rulers, necropolises filled with traps and treasures. And this being the Endless Night, some of those dead rulers still dominate their domains, whether they take the form of undead or simply malevolent will.

These layers aren’t bound by the laws of physical space. They can be tiny, or they can be seemingly infinite. A desert may wrap back upon itself, and the alleys in a city could twist in impossible ways to always return you to the main square… or you could just come to an absolute edge, where everything falls away into an endless and all-consuming void. To move from one layer to another you must either employ spells of your own or find a portal that connects the two realms. Sometimes these are fairly obvious: a massive gate standing alone in the desert, a pit filled with swirling shadows. In other cases, the connection could be entirely abstract. If you are in the valley of the Bone King and you want to get to the desert of the Queen of All Tears, the answer is simple: all you have to do is sincerely cry, and the tears themselves will take you there.

Of course, if you want to explore the Endless Night there are problems you will face no matter where you go. The realm itself constantly consumes light and life. In 3.5 D&D terms it is minorly negative dominant. Unless you’re protected by some form of warding magics, the Night will continuously drain away your life energy, ultimately consuming your body and leaving nothing but a shadow. Even if you’re protected against this effect you must still deal with the darkness. All light sources in this plane are reduced to dim light. The radius of illumination doesn’t change, but no light can banish the perpetual gloom. Spells that use negative energy will be maximized (variable die rolls such as damage and healing have the maximum possible result; this doesn’t affect attack rolls or saving throws), while spells that rely on positive energy are minimized.

THE CONSUMING DARKNESS

Many of the layers of the Endless Night are purely symbolic. These ruins have existed for as long as the plane itself. Many… but not all. Most of the planes don’t interact with one another. The armies of the Battleground endlessly battle each other — they don’t lay siege to the Realm of Madness. The planes are self-contained and focused on their own slivers of reality. But the concept that defines the Endless Night is the hunger to consume light and life, along with the inevitable downfall of all things. And when all the forces align just perfectly, fragments of other planes can be pulled into the Endless Night. These fragments are caught on the edge of the night, the same way mortal dreams drift around the heart of the Realm of Dreams. Over time, they are drained and pulled closer to the core, until ultimately they are fully assimilated into the plane as a new bleak layer. Typically mortals will be transformed into shadows or other forms of undead; immortals might become yugoloths, or twisted into dark mockeries of their former selves.

The Drifting Citadel is just such a layer. This floating tower was once a library; in Eberron it was part of Syrania, while in Phoenix it was created by the Faeda Concord. Now it drifts through a icy void, grand windows shattered and books fallen from their shelves. Shadows of sages clutch at books with insubstantial fingers, never able to turn a page. The angelic librarians are now tormented spirits who hunger for knowledge, draining the memories from any creature unfortunate enough to fall into their grasp.

With this in mind, as you create layers of the Endless Night, consider the history of the layer. Is it a symbolic layer that has always been desolate? Or is it a place that once knew light before it was consumed by the Endless Night? Beyond this, you can also explore the fragments that are in the process of being consumed. Fragments of outer planes might understand what’s going on and be trying to find a way to fight it… but pieces stolen from the material plane may have no way to know what’s happening to them. So you could have a small kingdom ruled by a tragic lord who wields great power and yet is being consumed by darkness… an inescapable realm shrouded by mists, seeming cut off from the rest of the world. All of which is to say that this would be an easy way to add Ravenloft into a setting, as a piece of reality that is under siege by the dark powers of the Endless Night. In Eberron, the Mourning could be what happens when a piece of reality is consumed… in which case Queen Dannel could still rule over a version of Cyre that is being consumed by shadows. It could be that this wound will never heal, and that the Mournland is now a permanent part of Eberron; or it could be that given time restorative power will flow from the Eternal Dawn to restore the blighted land, creating a new Cyre. These unassimilated fragments don’t have the negative dominant trait, and can contain living creatures… but the consuming hunger of the Endless Night should always be felt in some way.

Overall, it might seem like this is something the powers of other planes would try to stop. But the it cannot be stopped, and they know it. It is part of the machinery of reality. The Endless Night consumes and fragments are lost. Those pulled into the darkness can fight against it, but the ultimate outcome is inevitable. Were it not for the Eternal Dawn, it would eventually consume everything. But as the Night consumes, the Dawn restores, and so balance is ultimately maintained. The question a GM must decide is whether the fragments that are consumed are random… or whether the Empress of Shadows has some discretion over this. It might not be possible to fight the coming of night… but it could be that planar emissaries come to the Amaranthine City to negotiate with the Empress of Shadows and turn the hungry darkness in a different direction.

DENIZENS OF THE ENDLESS NIGHT

The most numerous inhabitants of Mabar are shadows. These semi-sentient spirits linger in places where you might expect to find people, forlornly pantomiming the roles of the absent inhabitants. You’ll find the shadows of children playing on the corner of a Mabaran street, or the shadow of a priest silently praying to an absent and unknown god in a shattered temple. Many sages who study the planes believe that these shadows are tied to mortals… that every sentient mortal creature has a shadow in the Endless Night, a manifestation of their darker impulses. These shadows don’t speak and are driven by impulse and instinct. They hunger for the lifeforce of mortals, and if planar travelers aren’t protected by magic they may be swarmed by hungry shadows.

The more desolate planes are home to nightshades. These powerful creatures are conduits of negative energy. In the obsidian desert, massive nightcrawlers lurk in the dark sands while nightwalkers lay claim to the ruins and rule over the shadows. Nightshades often attack fragments, feeding on the energy of the fragment and accelerating its assimilation. In these attacks, nightcrawlers may rely on raw force which nightwalkers may lead armies of undead. While intelligent, nightshades are more alien and primal than the yugoloths and rarely negotiate or converse with outsiders.

If the Endless Night has a heart, it would be the Amaranthine City… a metropolis that fills an entire layer. Nothing flourishes in this plane; banners are tattered and gardens are withered. But it is still wondrous in the scope of its cyclopean towers and grand fortifications. It is the capital of an empire in decline, and yet the hint of what it was at the height of its glory makes it wondrous even when faded. And it is no empty shell; it is a city alive with activity. This is the seat of the Empress of Shadows and her people; in D&D terms, these are the yugoloths. These are spirits of darkness, embodiments of hunger, despair and death. To all appearances, the yugoloths are citizens of a vast empire; they maintain that all things were once in darkness and eventually will be again.

Many yugoloths serve in the army. The Legion of Night lays siege to the fragments of planes that have powerful inhabitants of their own. The yugoloths do battle with angels and devils trapped in their doomed fragments, until the fragments are ultimately fully drained, assimilated, and their immortal inhabitants converted to a form more suited to the Endless Night. It’s questionable if these battles actually speed up the assimilation, or if they are simply a way for the fiends to pass the time; certainly, they enjoy these struggles.

Other yugoloths are gardeners… but what they cultivate is darkness. Most gardeners work with shadows. They search for promising shadows and use their abilities to strengthen a shadow in certain ways. It’s thought that this in turn feeds the darkness of the mortal tied to the shadow, potentially filling them with despair or driving them down dark paths. When the mortal eventually dies, the yugoloth can harness and refine the essence of the shadow, which can be used to create tools, elixirs, or works of art. While most gardeners work with shadows, some go into the fragments of the material plane that are being assimilated, twisting and tormenting the mortals trapped their in slow and subtle ways.

These are common paths, but there are many others. Some are philosophers and oracles who contemplate the nature of entropy and the way in which things will end. Some are artists and artisans, crafting shadow and spirit to create tools and weapons (which can cause death and despair should they make their way to the mortal world). And some serve seemingly menial roles in the Amaranthine City.

There are many other lesser inhabitants of the plane. Succubi are lesser spirits that embody emotional pain and loss. Some succubi are solitary and prey on mortals in fragments, while others live alongside the yugoloths and ply their wiles on them; the suffering of a fiend is just as satisfying to them as that of a mortal. Other succubi are gardeners, and some believe that a succubi can drain the love from a mortal heart by bleeding it from their shadow. And last but certainly not least, the Endless Night is home to undead. Most of the undead are symbolic: the endless skeletal armies of the Bone King aren’t actually the remains of mortal beings, and the Bone King himself, while he appears to be a lich, was likewise never mortal. Spectres and wraiths generally exist as predators, halfway between the Nightshades and the shadows. Some believe that when a vampire or lich is finally destroyed, its essence is pulled down into Mabar where it persists as a wraith… denied the eventual rest granted to other spirits of the dead, forever driven by the hunger of the night. Most are likely driven mad by this ordeal, but it’s possible that a vampire slain in a campaign could be encountered again as a spectral lord in the Endless Night.

TOUCHING THE MATERIAL: EBERRON

In an Eberron campaign, the Endless Night is the plane of Mabar. It affects the world in a number of ways: through manifest zones, coterminous periods, the actions of the plane and its denizens. Beyond this, some believe that Mabar is generally a source of despair and desolation, that it drains both emotional and physical energy from the world. While this is unproven, it is definitely the source of negative energy. Necromantic magics that sap energy or drain lifeforce draw on the power of the Endless Night. This is also the power that sustains most undead. Skeleton, vampire and wraith are all animated by the power of Mabar. This is the source of the vampire’s endless hunger and the draining touch of many undead. But even lesser undead innately draw life energy from the world around them. Typically this ambient drain is slight enough that there’s no mechanical effect; but this is why a haunted tomb will often be surrounded by dead plants and shriveled vines. The priests of Undying Court assert that negative undead are slowly destroying the world and that eventually this will cause irreparable harm; this is why the Aereni Deathguard seek to track and destroy Mabaran undead whenever possible.

One point here is the common confusion between Mabar and Dolurrh. Dolurrh is the realm of the dead, but it’s not the plane of death. Dolurrh is a place of transition. It is where the souls of the dead go after death, where the burdens of life are removed. So Dolurrh is where people go when they die; but Mabar embodies the idea of death, of inevitable loss and the end of all things.

COTERMINOUS AND REMOTE

According to the Eberron Campaign Setting, Mabar becomes coterminous for three days every five years. During these periods, there is a general increase in the amount of negative energy in the world. Shadows grow deeper and colder, and effects that rely on negative energy are strengthened. When one is alone in a dark place, this energy saps both strength and hope; solitary people are more likely to succumb to illness and despair. As a result, during these periods people generally come together to hold back the darkness. Communities gather around bonfires and sing or pray together; friends or families might gather into one abode for the duration, as bonds of love and friendship are a source of positive energy.

The Eberron Campaign Setting makes the consequences of the phase quite severe, stating “During the night and while underground, travel between the planes is much easier—simply stepping into an area where no light shines can transport a character from Eberron to Mabar, and barghests and shadows emerge from the Endless Night to hunt the nights of Eberron.” I consider this to be overstated for dramatic effect. Both of these things are possible, but here again, positive energy holds these effects at bay… and positive energy comes from light, life and love. So when Mabar is coterminous it is dangerous to go in the basement of the creepy abandoned house, or to wander alone on the moors at night. But if you’re in a house with your family and friends celebrating and singing around a roaring hearth, you don’t have to worry about being killed by a shadow when you go to the pantry. A child conceived during this period would have a chance to be born as a Mabaran tiefling… but in theory, if they child is conceived in love, that positive energy should prevent this.

While it might be possible to be transported to Mabar by passing through a shadow in a desolate place during the coterminous phase, I wouldn’t have such an effect take you to the heart of Mabar, where the minor negative dominant aspect would kill a normal person within minutes; instead, I’d have them pass into a mortal fragment that’s currently on the edge of Mabar and being consumed. Which is, again, essentially Ravenloft. You go walking on the moors at night, pass through dark mists, and find yourself in a tiny and tragic kingdom besieged by despair.

On the other hand, when Mabar is remote effects that use negative energy are impeded; spirits are generally higher (though this effect is not as dramatic as a time when Irian is coterminous); and undead are often gripped with ennui.

MANIFEST ZONES

All manifest zones to Mabar are strong sources of negative energy. Even if this doesn’t produce a direct mechanical effect, it is always the case that a Mabaran manifest zone is an excellent place to perform any sort of ritual that draws on negative energy. Other than that, here’s a few possible traits of Mabaran manifest zones.

- Blighted or unnatural vegetation.

- Low fertility and reduced resistance to disease. Creatures born in the region might be sickly, or you might get unnatural creatures (like Mabaran tieflings).

- Psychological gloom: a tendency towards despair, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts.

- Presence of shadows, wraiths, or other undead. While these can be shades of mortals slain by other undead, they are typically just manifestations of Mabar itself – embodiments of consuming darkness.

- Skeletons or zombies might spontaneously animate from corpses. Such undead don’t have any of the memories of the body and will typically seek to kill any living creatures they encounter.

- Unnatural darkness; light sources could be reduced, so even the brightest source only produces dim light. You could even have an area that is permanently shrouded in magical darkness.

- Spells and effects that rely on negative energy could be enhanced or even maximized; undead could be strengthened.

- Shadows could take on a life of their own without becoming fully formed aggressive monsters. It’s not that they exist independently of the things that cast them, but they might move in impossible ways or respond to actions around them.

Most of these don’t sound like very welcoming traits, and few people would likely choose a Mabaran manifest zone as a place to build their town. But there are reasons for doing it. We’ve established that in Karrnath, Blood of Vol communities often build temples in Mabaran manifest zones and perform rituals that help to contain the negative impact of the zone — and that some of the terrible famines in Karrnath were the results of soldiers seizing these towns and temples and failing to maintain these rites, resulting in sudden and dramatic blights. Beyond that, unnatural vegetation or minerals infused with Mabaran energy could have useful effects. In The Thorn of Breland books I talk about nightwater — water infused with Mabaran energy — as a common component used in disarming wards and magical traps.

So a Mabaran zone could be occupied by people trying to contain its effect or by necromancers channelling it; but often, they’re likely to be shunned areas in the wilds.

SCHEMES AND ADVENTURES

Do the denizens of Mabar ever have schemes that reach into Eberron? How could it play an interesting role in an adventure? One of the simplest ways is simply to work a manifest zone into a story. A necromancer has a tower in a blighted grove, and this empowers their magics and undead minions. The PCs take on the necromancer and defeat him. But when they return they discover that the necromancer’s work was holding the power of Mabar at bay, and the blight is spreading. Can they find a way to restore the balance? What if someone has to stay in the tower? Does one of the villagers have the talent? Or do they need to find another necromancer willing to hold the post – and can they trust her with this power?

Manifest zones could inspire many stories or interesting encounters.

- Shadholt is a small village hidden in the woods of Karrnath… a village populated almost entirely by Mabaran tieflings. The tieflings harvest vegetation and dragonshards infused with Mabaran energies and can make interesting elixirs and items. Perhaps they simply wish to be left alone… but an encounter with superstitious foresters could lead to a conflict with the local warlord. What side will the PCs take? Are the tieflings innocent, or are they using the powers of Mabar to prey on their enemies? Or is Shadholt the source of an addictive drug that’s been spread ing across the region?

- Passing across a moor, the PCs are set upon by the shadows of wolves and hawks. The following dawn, they discover that one of the PCs is missing their shadow… it’s been lost in the manifest zone. Do they need to go back and find it? If so, how? If not, what does it mean that the character no longer has a shadow?

- The PCs discover that House Thuranni is experimenting with the potential of the Mark of Shadows, seeking to channel the power of Mabar. There’s a research center in a Mabaran manifest zone. What happens if the experiments work? Are the elves in full control of their powers? Or are they consumed by their own shadows, leaving dark hearts cloaked in flesh wielding terrifying powers?

Overall, the denizens of Mabar have no interest in Eberron; they have everything they need in Mabar and its fragments. However, just like the Daelkyr or the Kalashtar Quori, you could have an individual or small group of spirits that take an interest in Eberron. Here’s a few possibilities.

- A disguised succubus is a scholar of loss, subtlely engineering disastrous tragedies for the people of a small community in order to study their reactions. Alternately you could take the same concept but she could be targeting powerful, successful individuals — such as player characters — instead of a particular place.

- A small group of Yugoloths are studying the world and choosing the next location that will be consumed by Mabar. The consumption will happen, even if the Yugoloths are defeated… but can the damage be minimized?

- A yugoloth artisan crafts artifacts and sows them into Eberron to cause death and despair. A weapon forged in Mabar could be a literal demon — a battleloth — or it could possess great power but bring tragedy to the one who wields it. A villain could cause great havoc with this night-forged blade; once the villain is defeated, will a PC claim the blade or leave it be?

- A nightwalker has broken through into Eberron, turning a Mabaran manifest zones into a gateway. The dead are rising in response to the nightshade’s call, and it has a force of nightcrawlers and nightwings. The Nightwalker has no agenda other than destruction, despair, and drinking in the energy of the world. Where is this gateway? What will it take to close it and contain this threat?

- Queen Dannel’s Cyre has been pulled into Mabar. There’s no way to reclaim it and return it to Eberron, but the now-vampire Dannel has a bigger goal. In Mabar, everything must end… even the yugoloth order. Dannel believes that she can overthrow the Empress of Shadows and become the new immortal overlord of the realm… but she needs the help of epic-level PCs to do it. Will they help transform Cyre into the new heart of the Endless Night?

The idea of the consumed fragments opens up another host of story possibilities.

- Forced out into the wilds during a Mabaran coterminous period, the PCs find themselves in a strange land. This could be a familiar town that’s now suffering from dangers and threats; can the PCs figure out what’s going on, and if it can’t be stopped can they help friends escape? It could be a realm pulled out of history, time slowed by the process of assimilation — the last stronghold of Karrn the Conqueror or Malleon the Reaver. Or it could be something entirely new, like Ravenloft.

- An angel of Syrania reaches out to the PCs. Something vital is trapped in a Syranian tower that was pulled into Mabar. If the angel goes to the fragment, it will be trapped there forever; but mortals could enter the fragment, retrieve the relic and escape. What is the relic? What else might they find in the lost tower?

- Similar ideas could take the players into the heart of Mabar itself. What treasures are hidden in the tomb of the Queen of All Tears? What secrets lie in the scattered tomes of the Drifting Citadel?

All of these ideas are literally off the top of my head, and I’m sure you can come up with others. Share your ideas in the comments!

THE DEEP DUSK: PHOENIX DAWN COMMAND

Phoenix: Dawn Command doesn’t have the complex cosmology of D&D. The Dusk is the realm that lies between life and death, a realm of spirits and magic. When a Phoenix dies, they go to a crucible – a pocket realm within the Dusk where they can earn their way back to the Daylit World. But there’s more to the Dusk than most Phoenixes ever see. The greatest of the Fallen Folk may have their own domains within the Dusk, and there can be great mystical engines left over from the Old Kingdoms, or simply from the framework of reality.

Within Phoenix, there’s a few ways you could use the Endless Night. Perhaps the Phoenixes face a great force of darkness striking against a community of innocents — a Nightwalker leading a legion of hungry wraiths and animated corpses. Destroying this being requires the Phoenixes to join their power together, sacrificing all their sparks to drive it back into the dusk. But instead of waking in their crucibles, the Phoenixes find themselves in the Endless Night, pulled into it by the spirit they banished. Can they find a way to escape the Deep Dusk? And what happens if they die before they do?

You could also explore the idea of the hungry realm… to have a piece of the Empire pulled into the Endless Night while the PCs are defending it. The life is being drawn out of it, and shadows lash out at the innocent. Can they find a way to return this farm/village/city to reality? And again, what happens if a Phoenix dies in this place? Do they simply return to the Night? Are they seemingly gone forever… and if so, is this what actually happens or have they simply been returned to the Daylit World?

Another possibility is to explore the idea that the layers of the Endless Night are all pieces seized from the Daylit World. Perhaps the Endless Night was created as a way to avoid the doom of the Old Kingdoms, preserving communities in some fashion (albeit a dark one); now the threat of the Dread has brought this old magic back to life, and it’s going to start stealing cities anew.

Q&A

How do Mabar and the Plane of Shadows both exist in the same cosmology while remaining distinct? What is the difference in themes between these two Planes? Can the Plane of Shadows have its own Manifest Zones?

This is spelled out on page 92 of the Eberron Campaign Setting. The entire reality of Eberron — including its thirteen planes — is enfolded by the astral plane; the ethereal and shadow planes encompass the material plane but don’t touch the other planes. The easy way to think of this is that the Shadow Plane is the darkness that lies between realities. It has no meaning as Mabar does; it is simply a dark space outside of reality. Spells like shadow walk let you use it as a shortcut through space, or even in theory as a conduit to move between realities. But it isn’t part of the creation of the Progenitors. It has no meaning and it doesn’t shape reality. It’s not part of the planar orrery, and as such it never becomes coterminous or remote and it doesn’t create manifest zones; it simply is.

A minor qualm, but it seems that Mabar as portrayed here ultimately prevails when it exceptionally interacts with other planes, as Syrania in the post. Yet, using the same example, after night comes dawn…

That’s exactly the point. The night consumes every day… and the dawn eventually overcomes each night. The section on “The Consuming Darkness” calls this out: Were it not for the Eternal Dawn, (The Endless Night) would eventually consume everything. But as the Night consumes, the Dawn restores, and so balance is ultimately maintained.”

The Endless Night embodies the idea of despair and the inevitable end. But the Eternal Dawn — in Eberron, Irian — embodies the idea of hope and the indomitability of life. Anything Mabar can consume, Irian can restore… though both of these things take time. But yes, Mabar will ultimately prevail against any fragment it consumes because that fragment has been pulled out of its own concept and into the Night, which is defined by that inevitable defeat.

Is it possible for there to be Mabaran celestials, or good-aligned spirits from Mabar? For that matter, are there any Irian fiends, or evil-aligned spirits from Irian?

Certainly, in both cases. But the point is that any spirit of the Endless Night is about the concept of death, loss, despair. If you can find a way to make a being who’s a positive embodiment of these things, it could be good. For example, you could have Small Mercies — little spirits that kill those who are suffering unendurable torment. Technically they’re good; they are helping those who suffer. But their tool is still death. You won’t have a spirit in Mabar that seeks to prevent death, because that’s something that belongs in Irian. Look at Shavarath: you have noble celestials fighting vile demons, but they are all fighting; you’re not going to find a spirit from Shavarath that thinks peace is a good idea, unless it’s the peace that will come when we win our noble battle against the enemy.

So any spirit of the Endless Night will somehow embody death or loss, entropy or despair. If you can think of the positive aspects of this and personify it, that could be a Mabaran celestial. Conversely, Irian is about life and love, new beginnings and hope. If you can find a way that these things could be negative, you could have an fiend that embodies that. Perhaps there’s a spirit that spreads false hopes… though again, if its ultimate goal was to cause despair, it would belong in Mabar. Meanwhile, in a fragment of Irian being consumed by Mabar you can have the embodiment of hope that is struggling against despair; and within a fully consumed layer, it might still exist as the embodiment of crushed hopes and disappointment.

With all of that said: Bear in mind that just as celestials can fall, fiends can also rise. In the same way that an angel can become a Radiant Idol or rebel Quori can become Kalashtar, you could have a yugoloth who defies their nature and purpose. However, like the Kalashtar Quori and the Radiant Idol, if they want to maintain that identity they’d likely have to flee from Mabar.

If Mabar is indeed Death itself, then how to the Seekers argue their use of its powers. Logically, the Undying Court would be right; however, it is important to the role of the Blood of Vol that they too would have arguments. I like the idea that they do their part to contain the spread of Mabar’s power in its manifest zones, but why wouldn’t they agree with the Court that Mabar is basically a hostile plane and not to be meddled with?

It’s like fire, or nuclear power, or electricity. All of these are dangerous if you don’t know what you’re doing; when harnessed by someone who understands them, they can be used to do good. An educated priest of the Blood of Vol would certainly agree that the power of Mabar is inherently dangerous — as shown by their working to contain the danger posed by manifest zones — but that’s exactly the point: they can contain that danger. They believe that their knowledge and understanding allows them to use this dangerous power in a positive way, just as we are comfortable using electricity and nuclear power in our daily lives.

Looking to the Undying Court’s assertion that all use of Mabaran energy is a threat to the world, Aerenal is a fairly isolationist country and they haven’t blanketed the Five Nations with this view. Even if they did, it’s a perfect mirror to the issue of climate change. Aerenal has logic on their side: it’s energy from the plane of Death and look at what it does in manifest zones — why use it? The Blood of Vol takes the role of people who say that cleaner coal is the answer to climate change: they know what they’re doing, they’re not going to throw away a useful tool because of some crackpots, and they don’t see any proof that things are as bad as the elves say. Plus, given that the Undying Court eradicated the line of Vol they CLEARLY have a vendetta against the BoV and this argument is simply driven by that vendetta; they’re making up excuses to persecute the BoV. Don’t be misled!

Short form: Any cleric of the Blood of Vol will tell you the power they wield is dangerous, but generations of their ancestors have learned how to master that power and wield it safely. And any arguments that it’s poisoning the world are ridiculous — again, generations of their ancestors have used it safely.