The second episode of the Manifest Zone podcast is up! The subject is the Last War. As the podcast is a stream of consciousness discussion, I’m going to do a follow-up post after each episode… think of it as my commentary track.

The Last War is a critical part of the story of Eberron. By default, an Eberron campaign begins in the year 998 YK. YK means “Year of the Kingdom” — specifically, the Kingdom of Galifar, which brought together the disparate nations of Khorvaire almost a thousand years ago. Galifar was prosperous and generally peaceful for centuries. However, when King Jarot ir’Wynarn died in 894 YK, his heirs refused to follow the standard practice of sucession. The five provinces of Galifar — Aundair, Breland, Cyre, Karrnath and Thrane — split apart, forming what are now known as the Five Nations. A century of war followed as each heir attempted to rebuild Galifar under their rule. The war finally came to an end following the Mourning, a mystical cataclysm that completely destroyed the nation of Cyre, transforming it into the warped region known as the Mournland. No one knows the cause of the Mourning. Was it a weapon, and if so, are its creators developing a second one? Was it the result of using too much war magic, in which case continued conflict could result in further destruction? The Mourning occurred in 994 YK, and within two years the war formally ended with the Treaty of Thronehold in 998 YK. But no one WON the war, and few people are happy with its outcome. The mystery of the Mourning is holding further conflict at bay, but sooner or later that mystery will be solved… and most believe that when it is, war will be inevitable. Some rulers are actively pursuing the cause of peace, while others are already preparing for the next battle.

The Last War serves a number of important functions. First and foremost, it shatters the established order and creates an era that is filled with conflict and uncertainty. Thanks to the war, we see a number of critical developments:

- New Nations. Darguun, Valenar, Q’barra and Droaam were all born from the conflict, as new forces seized land once claimed by Galifar. The Eldeen Reaches expanded into Aundair, while the Mror Holds and Zilargo asserted their independence. Some of these shifts were more dramatic than others; for Zilargo it’s virtually a semantic change, while Darguun and Valenar represent violent upheavals of the previous order.

- Balance of Power. As a single market, Galifar had the power to dictate terms to the Dragonmarked Houses – something it did with the Korth Edicts, which established that dragonmarked house can’t hold land, titles, or maintain military forces (with exceptions made for House Deneith). Now the nations need the houses more than the houses need any one nation. If the houses do decide to violate the Korth Edicts, who would have the power to enforce them?

- Innovation. The Last War drove innovation, and within the last century there have been many critical developments. First there were warforged titans, and this led to fully sentient warforged. The eternal wand is a critical advance in the science of wands, being both more accessible and reusable; the next step could be a wand that anyone can use. The airship was developed during the war, which is a critical point: air travel is still very new in Khorvaire! These are a few major examples, but in my opinion this is representative of a broader range of advances, as both houses and nations struggled gain an edge in the conflict.

- Opportunity for Adventure. The Mournland is the world’s largest dungeon, and it’s sitting right in the middle of the continent. Cyre was the richest of the Five Nations, and all its treasures are lost in a twisted wasteland filled with monsters. If you prefer espionage, the Five Nations are all vying for power and position as they prepare for whatever happens next. This can even extend to straight pulp adventure. You’re searching for the Orb of Dol Azur in Xen’drik? Well, so’s the Order of the Emerald Claw… and if they get ahold of it, you can be sure they’ll use its power against Breland in the Next War!

Beyond this, the Last War is a source of infinite character hooks. The war ended two years ago. The typical soldier in the last war was a first level warrior (that’s an NPC class from 3.5 – a crappy version of the fighter – if you don’t know the term). As even a first level PC classed character, you are more talented than the typical soldier. So, if you’re a fighter… did you fight in the war? If so, were you a mercenary, or did you fight for one of the nations… and if so, which one? Are you still loyal to your nation, or are you disillusioned by what you’ve been through? And if you didn’t fight in the war even though you clearly had the skills to do so, why didn’t you fight?

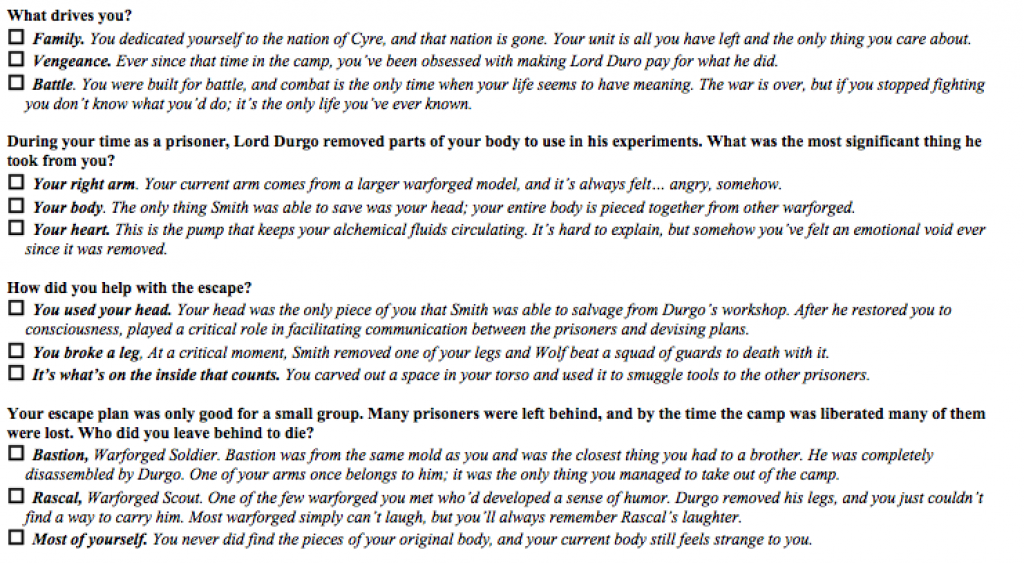

This is something you can develop as deeply as you wish. For some people, this is a way to really add depth to a character. What happened to you during the war? What were your greatest victories, and what did you lose? Were you a war hero, or were you just a grunt in the trenches? Did you spend any time in a POW camp, and if so, what did you endure? How about your family – how did the war affect them? If your character is religious, how did the war and the Mourning affect your faith – was it a solace to you in difficult times, or has it forced you to question your faith?

This can easily form the foundation for a story that unites an entire party of adventurers. One of my go-to ways to start a campaign is to establish that the players were all part of a unit of soldiers during the last war. With that in mind, I’ll ask each character to figure out how their concept fits within that mold. You want to play a warforged fighter? Easy, you were made for the war. You’re playing a warlord? Congratulations, you’re the captain of the unit. Wizard? OK, you were the arcane support. My standard nation of choice is Cyre, because while no one won the war, Cyre definitely lost it. As a Cyran soldier, you have no homeland; you’ve lost everything; and yet, you still have a particular set of skills. Why WOULDN’T you become an adventurer? It’s essentially Mal and Zoe from Firefly. And like Firefly, what I like to do with this set up is to actually set the first adventure (or two) during the war: so we get to see your group working together as a unit, and we get to see some of the things they went through. You’ve got to hold an undersupplied post against an advancing army of Karrnathi undead. It’s a fight that can’t be won, and in the process you’ll have to make difficult decisions, and you’ll deal with a Karrnathi commander who you will surely come to hate. Once we resolve that, we’re going to talk through the next two years: how you moved from being soldiers to adventurers. But you’ve got a foundation to work with. You’re not strangers brought together by an old man at a bar. You’re comrades in arms. You’ve faced the undead together. And when that Karrnathi bastard shows up again working for the Emerald Claw, you’ve got a real reason to take him down.

In the episode of Manifest Zone, we talk about how war can leave fairly intense scars. You don’t have to dig that deeply if you don’t want to. You can establish that your fighter fought for Breland and leave it at that. You may not want to burden your character with a crisis of faith or PTSD. You could very well ask how it benefits YOU to damage your character, or to hand the GM tools to make your life difficult. For me, it’s not about given the GM “things to use against you”, because as the GM I’m not your enemy. At my table, what we are trying to do is to build a story together… and for that story to be as dramatic and compelling as possible. These sorts of scars give your character depth. They give you trauma that you can overcome, and they give you things to fight FOR beyond simply getting a better magical sword. Just looking at, for example, The Force Awakens: Finn is a former conscript who’s fled war and ultimately works up the courage to fight the people he once fought for – even though this pits him against people he once served with. Rey is an orphan who’s avoided the conflict and lived as a scavenger. And Poe is the soldier who believes in his cause. In Firefly, Mal is an officer who was deeply devoted to his cause, only to have that faith crushed in defeat; but it’s still there, underneath his mercenary cynicism. Having flaws gives your character depth. In 5E D&D, these elements can be worked into Backgrounds; at some point I may post something that explores backgrounds particularly well suited to Eberron.

So: the Last War is a source of upheaval and change that creates opportunity for adventure and adventurers. It provides a wealth of hooks for character development. It can also provide a host of possibilities for adventures. Setting aside the Mournland, you can have to deal with mystical weapons gone terribly wrong, from a rampaging titan to a secret program that sought to create magebred supersoldiers. You can have “dungeons” anywhere, because rather than having to rely on ancient ruins you can have NEW ruins created during the war. You can track down war criminals or delve into espionage. Whether you care about a country or are just looking for opportunities, the shadow of the Last War creates many possibilities.

THE SHAPE OF THE WAR

With all that said, many people want a better sense of the actual nature of the war. Was it more like World War I, with grueling trench warfare and soldiers being ground up on a relatively static front line? Was it a time of constant change, with cities being seized and lost? Was it like modern warfare, with air strikes and similar attacks inflicting damage far beyond the front lines?

The sourcebook The Forge of War provides the canon answer to these things and is your best source for in-depth information, since I don’t have time (or permission) to write a sourcebook on the Last War. With that said, I didn’t work on The Forge of War and it is the canon source I have the most issues with. It doesn’t delve as deeply into the concept of innovation as I’d like, and doesn’t explore the question of what new weapons and tools were developed in the war. It ignores many other canon sources; one of the most infamous examples is its statement that Thrane lacked any decent archery support, when archery is a devotional practice of the Church of the Silver Flame and should be one of the greatest strengths of Thrane. With that said, FoW provides a POSSIBLE overview of the course of the war.

As for my answer: The Last War was all of these things. It lasted for a century, and that wasn’t a century of constant, unending total war. It had its slow periods, with soldiers glaring at one another across the static front lines. And these were punctuated by periods of intense conflict, of shifting alliances and changing borders. And while it was largely concentrated on the fronts, there certainly were magical attacks that pushed beyond the front to cause indiscriminate damage further back. Often this would be triggered by a new magical development. When Karrnath first incorporated undead into its armies; when Cyre fielded the first warforged titans; when Aundair pioneered new long-range war magic. One issue to me is that I feel that we haven’t established the primary weapons used in the war. The magic items and spells that PCs use are geared towards squad-level combat with small groups of powerful individuals, because that’s what PCs are. But a fireball that inflicts 6d6 damage over a thirty foot radius is both overkill and too small an area to have much impact on a group of a thousand first level warriors. So what spells did war mages rely on? Do you take the principle of cloudkill to make a larger-scale gas attack… and if so, did someone invent the equivalent of a gas mask? One advantage of this approach — the idea that most spells used in the war were lower damage but larger area — means that faced with such things, PCs get to shine on the battlefield. A 6d6 fireball may be a grave threat to a third level PC. But if the magical bombardment inflicts 1d6 fire damage over a hundred foot radius, it’s still a serious threat to the common soldiers – but the PCs can miraculously survive a few blasts, which is after all how we want this movie to go.

The basic principle of Eberron is that it’s a world in which arcane magic has been used to solve the problems we’ve solved with technology. So if you look to the common tools of modern warfare — mines, tanks, artillery — I feel all of these should have their parallels in Eberron, but based on arcane principles. The warforged titan is one answer to the tank; I could imagine a variation on the apparatus of Kwalish as another. In my novels, we see a variation of mines (based on the principle of a glyph of warding) and artillery — specifically the siege staff. Following the idea that a wand is a form of mystical sidearm and that the staff is physically larger and more powerful, a siege staff is a staff made from a tree trunk — thus capable of holding even more energy and projecting it farther. Neither of these things were ever given mechanics, but it’s the sort of thing I’d like to see addressed some day.

Tied to this, in a previous post Zeno asks: It is said that Titan Warforged was created for war. That sometime devils has been released on opponents. I wonder why 1st level commoners should be thrown in a war like that. A single titan Worforged could kill a whole army.

It’s true: the typical soldier in Eberron has no chance against a warforged titan. Just as common soldiers in our world have trouble when faced with tanks, chemical weapons, or incendiary bombs. It sucks to be a typical soldier when you have to charge up a hill against an entrenched machine gun. War has never been fair, and it’s not fair here.

With that said: the typical person in Eberron is a first level commoner, but the typical soldier would be a first level warrior; a veteran might be second level. Small difference, but a difference nonetheless. Nonetheless, a second level warrior wouldn’t stand a chance against a warforged titan. Why would they be thrown into that war? Because that’s all they had to work with… and because it’s what also forms the bulk of the opposing forces. Infantry is the best tool to hold ground. Meanwhile, the warforged titan is a specialized and very expensive piece of military equipment that serves a specific role on the battlefield. Think of the warforged titan as a tank. If you’ve got a squad of soldiers armed with machetes or even standard smallarms, they simply aren’t equipped to deal with a tank. If they try, they’ll get killed. The same thing is true of a squad of warriors facing a warforged titan. In both cases, what you won’t see is the soldiers charging in and trying to hack the overpowering enemy apart with machetes. Instead, you’re going to have the following questions:

- Do we have access to equipment that allows us to overcome this threat? Do we have an arcane specialist with a wand or staff with a spell that can defeat this? Do we have a siege staff? Can we summon a planar ally? Essentially, do we have anti-tank weaponry in our unit? You see this in City of Towers, where the unit is faced with a military airship and requires a specialist to bring it down.

- If not, can we take advantage of the terrain? Can we lure it into swampy terrain where it will sink? Is there a minefield? Can we get it onto a bridge and collapse the bridge?

If the answer to these things is no, then they won’t engage it. They’d retreat and regroup. So IN THEORY a warforged titan could kill a whole army; in practice, the army would disengage.

On top of this, consider that military command would be tracking these things. Units with warforged titans, the capability to summon planar allies, and the like are exceptional; that’s exactly the sorts of units that would be tracked. So when that titan shows up and you have nothing to handle it, you get out of there and hope that command already has forces en route with anti-titan capabilities.

So yes: the warforged titan can slaughter a squad of typical soldiers, as can a summoned fiend or any number of other threats. Which means once the titan exists, people immediately began finding ways to deal with it — just as people in our world invented anti-tank weaponry. And this is great for House Cannith, which sells you the weapons, and then sells you the thing you need to counter the latest weapon, and then sells you the thing you need to counter the counter, and so on.

Could we get a brief overview of each of the Five Nations’ general tactics in the Last War?

Certainly. If they were a party of adventurers, Karrnath was the fighter. Aundair was the wizard. Thrane was the paladin. Breland was the rogue. And Cyre was the bard. This is a gross simplification – not addressing Breland’s industrial capacity or Cyre’s wealth – but it’s a good place to start as a mental image.

With that said, this could be the subject of a sourcebook. I’d refer you to Forge of War, but I don’t think they actually got this correct. So first of all: Galifar was a united kingdom, but its resources were spread throughout the five provinces. This is generally reflected in the culture of that province. So for example, Karrnath was the seat of Galifar’s military and the home of Rekkenmark, its premier military academy. Soldiers from across Galifar trained at Rekkenmark, and when the war began most returned to fight for their own nations. Likewise, wizards from all countries trained at the Arcane Congress in Aundair. So all sides benefitted from these resources initially. But the people of that province were the most committed to the concept embodied by those institutions; had the MOST people trained at those institutions; and held onto the institutions themselves and their resources as the war continued. So at the start of the war, every nation had spies trained by the King’s Citadel. But Breland had the most of them, and had the facilities, records, and resources of the Citadel itself. With that in mind…

Karrnath was the seat of Rekkenmark and the Royal Army. Karrnath has always had a harsh, martial culture. In general, they had the most disciplined and best-trained soldiers, and had exceptional heavy infantry and cavalry. I’ve always felt that they had decent war magic, though obviously inferior to Aundair and extremely focused (primarily evocation). Karrnath was further distinguished as the war went on by the use of undead in battle. So in Karrnath you have stoicism, discipline, and general martial excellence… with a side dish of undead.

Aundair was the seat of Arcanix and the Arcane Congress, and has always had the edge in arcane magic. It is the smallest of the Five Nations, and has always relied on magic to make up for that. So Aundair would have the best mystical artillery, both using things like siege staffs and in terms of having the most actual wizards on the battlefield. They lacked the industrial capacity of Breland or House Cannith, but were always the leaders in arcane innovation… so to make a modern analogy, they didn’t have the MOST missiles and bombs, but they had the BEST missiles and bombs, and were the most likely to surprise you with something you hadn’t seen before.

Breland was the industrial heart of Galifar, and further was the seat of the King’s Citadel… which includes the intelligence agency of Galifar. So from the start they had the greatest numbers of spies, assassins, and other covert operatives. This was further enhanced by a strong relationship with Zilargo and House Deneith. So intelligence was always a strength of Breland. Beyond that, they had numbers and resources, and what they lacked in discipline they often made up for in spirit and charisma; so your rank and file soldiers weren’t as exceptional as you’d get in Karrnath, but they’d be more likely to have truly inspiring leaders, and to break the rules of war to try something new. I still think the rogue is a good analogy: Not as good in a straight up fight, but clever and unpredictable, and very dangerous if they can catch you off guard.

Thrane was the seat of Flamekeep and the heart of the Silver Flame. This shouldn’t be underestimated. While the Silver Flame is revered across Galifar, Thrane was its heart, and Flamekeep is where paladins and clerics would received their training. And this is critical, because the Silver Flame is a martial faith. The Silver Flame is about being prepared to defend the innocent from supernatural evil. Archery is a devotional practice, and every Thrane villager trains with the bow. Beyond that, the Silver Flame maintained its own army of Templars. The Lycanthropic Purge was the biggest example of templars at war, but on a smaller scale the templars were constantly hunting down and eliminating supernatural threats. Karrnath was the seat of the army; but the Thranes had if anything more soldiers who’d actually SEEN BATTLE, even if they hadn’t been fighting other humans. This also meant they had more hands-on experience supplying and supporting their forces than most nations.

In summary, Thrane’s greatest strengths were peasant militias, exceptional archers, morale enhanced by a shared creed, an experienced and disciplined force in the Templars, and beyond that, the greatest ability to bring divine magic to the battlefield. PC class characters are exceptional, but to the degree that there were clerics and paladins on the battlefield, Thrane had the lion’s share of them… and just as Aundair was most likely to produce a dramatic new arcane technique, Thrane was most likely to suddenly summon plaanr allies or otherwise turn the tide through use of divine magic.

Which leaves Cyre. Cyre was known as the center of art and culture, and in some way it wasn’t the best at anything… but at the same time, it also had a little bit of everything. Hence the bard — jack of all trades, not tied to any one path. Cyre also had the fact that according the the laws of Galifar, they were in the right — so back to the bard, strong morale. Finally, Cyre’s greatest asset was holding the wealth of the kingdom… which in turn meant that they could field the most mercenaries and draw the greatest amount of support from the Dragonmarked Houses. And it certainly didn’t hurt that House Cannith was based in Cyre. So Aundair had the BEST arcane magic; Cyre had considerably more of what could be bought from House Cannith. Cyran forces involved a lot of mercenaries (Deneith, Valenar, Darguul) and more warforged than any other nation… and like Breland, what leaders lacked in discipline and experience, they would attempt to make up for with charisma. As we all know, the heavy use of mercenaries had some pretty disastrous consequences down the line… but there you are.

That’s all I have time for now, but I will continue to answer questions over the course of the week. Let me know how you’ve used the Last War in your campaign and what you’d like to know about it! And check out the latest episode of Manifest Zone!

FOLLOW UP QUESTIONS

I seem to recall that Aundair took Arcanix from Thrane. If so, did they possess the arcane advantage they were known for at the beginning of the war? And if so, where did it come from?

This is from The Forge of War and is one of those the elements I strongly disapprove of. With that said, here’s my answer. The Arcane Congress has always been part of Aundair. It was founded by Aundair herself if the early days of Galifar, and respect for magic and education have both been engrained into the Aundairian character in a way no Thrane can understand. Arcanix — the greatest university and the seat of the Arcane Congress – is a floating citadel. It is also a mystical stronghold; Aundair’s greatest military asset its its arcane prowess, and Arcanix is, if you will, its Death Star. And like the Death Star, it’s mobile. It’s a floating institution, and when they seized a particularly desired stretch of land from Thrane and laid claim to it in the war, they moved Arcanix to that region. So it is true, Aundair took what is now Arcanix from Thrane during the war… but it wasn’t Arcanix when they took it.

You’ve established that the Keeper of Secrets is bound at Arcanix’s location. Would you say that she is tied to the town, the mobile fortress, or both?

As a GM, I’d definitely say she’s bound to the location. From a story perspective, this helps justify new developments at Arcanix tied to the presence of Sul Khatesh. I’d probably say that Hektula is manipulating Aundair and that shifting the location of Arcanix is part of the puzzle that will eventually free the Keeper of Secrets. But it could also simply be that Minister Adar learned of the location of Sul Khatesh on his own and has a team of sages seeking to tap into her knowledge and power… and we all know that will go well.

Why did the Five Nations refuse to recognize Droaam in the Treaty of Thronehold, when they recognized Darguun and Valenar?

On the surface, it’s easy to see all these things as being equals. Darguun and Droaam are both nations of monsters, right? Kind of. First there’s the issue of timing. Valenar rose over forty years before the end of the war; Darguun almost thirty years before the Treaty. Both fielded large armies during the course of the war. Both represented recognized civilizations. Essentially, both had proven that they weren’t going anywhere, and they had sufficient military forces that it was vital to get them to the table in the interests of establishing a general peace.

By contrast, at the time of the treaty Droaam had been around for a decade. It was an assembly of creatures whose cultures were largely unknown in the east; no one had really considered the idea that harpies or medusas we in any way civilized. And while Droaam brokered mercenaries through House Tharashk, it never fielded a true army during the war. It’s the closest thing Eberron has to a terrorist state. It’s something the people of the east didn’t believe would last and something they don’t WANT to last. They settled with Darguun and Valenar because they had to. Droaam wasn’t seen as a civilization deserving of respect or as such a significant threat that it needed to be placated. My novel The Queen of Stone explores the ongoing relationship between the Thronehold nations and some of these issues.

When suggesting your players to be war comrades, did you ever had problems in finding a place for druids and barbarians?

It’s generally an approach I’d use when I’ve got a group of players who don’t have character ideas they’re dead-set on — so it’s something where the players would build characters with the war story in mind, and I’d challenge THEM to figure out how the character fits.

Primal characters don’t have a strong role in any of the Five Nations, so it’s not an easy match. The first and most important question is whether they are driven by the mechanics of the class, or by its specific role in the setting. Do they want to be a barbarian because they want to be a savage outsider, or because they like the mechanical abilities of the barbarian class? If they want to be an outsider — a druid from one of the Eldeen Sects or a barbarian from the Demon Wastes — they need to think of what could cause a character with that background to serve with your nation. They could be a mercenary. In the case of a druid, they might not actually be part of the army; they could simply be a mysterious ally who’s chosen to help the squad. If your soldiers are Brelish, the druid could be one of the Shadows of the Forest who’s chosen to help against their enemies. In the case of the barbarian, I’ll note that among the Dhakaani, the barbarian class represents a martial art that involves a cultivated state of battle fury; they aren’t savages, they are specialized warriors. Your PC barbarian could follow this same path — having the abilities of a barbarian but not the flavor. Worst case scenario, say that the barbarian and druid don’t join the party until after the war… and if you do initial adventures set during the war, it’s a great time to have these players put on red shirts and play the warriors or experts who likely won’t make it through the adventure… and their tragic deaths can help bond the rest of the squad.

But the point of doing that “squad scenario” is to say “Make a character who would be in this squad.” If your players won’t be happy with that limitation, I wouldn’t follow this path.

About Karrnath: do you think people there had already a different relationship with undead and/or death? Were they more ready to accept undead soldiers than others?

Absolutely. It’s not always been presented clearly, but Karrnath and the Lhazaar Principalities have always been the stronghold of the Blood of Vol. The faith was well-anchored in Karrnath long before the war, and in Seeker communities you’d already have undead performing basic labor; they’d just never been harnessed and organized for war, and the Odakyr Rites (which produce the distinctive Karrnathi Undead) hadn’t been developed. In part this is tied to the idea that Karrnath is the harshest of the Five Nations in terms of environment, and its people were generally more receptive to the bleak outlook of the Blood of Vol. It’s not like the Silver Flame and Thrane; the number of Seekers is small enough that Kaius could choose to use them as scapegoats in the present day. But the faith has always been around in Karrnath and thus its people had more casual contact with undead than any of the other Five Nations.

Would a Karrnathi Silver Flame or Sovereign cleric, or maybe even a bard be DIFFERENT in his approach to the topic?

Mechanically or philosophically? Mechanically, no. If you want a different approach to undead, make a Blood of Vol cleric. Philosophically they’ve be more used to having them in mundane roles and thus less likely to see ALL UNDEAD AS ABOMINATIONS then their counterparts in other nations. The focus of the Silver Flame is protecting the innocent from supernatural evil; a templar raised in Karrnath knows that the skeleton working in the fields in that Seeker community ISN’T suddenly going to turn on the villagers. With that said, the Silver Flame has never had a strong foothold in Karrnath, precisely because its culture leans more towards the bleak pragmatism of the Blood of Vol; in my opinion, Seekers have always outnumbered the followers of the Flame in Karrnath.

Five Nations says Thrane was the nation Breland feared the most… I thought Breland was much stronger than all.

If Breland was “stronger than all” the war wouldn’t have lasted a century. Breland had more people and stronger industry. But Aundair had better magic and Karrnath had better soldiers. As for Thrane, I didn’t write Five Nations so I can’t tell you what they were thinking. But let’s look at a few key factors.

- Thrane and Breland share a significant border.

- Along with Karrnath, Thrane has the most militant culture among the Five Nations. Its people stand ready to fight supernatual evil… but that still means that they are combat ready and prepared to make sacrifices for their faith. Again, in my mind the peasant militias are one of Thrane’s greatest assets.

- Tied to this, I feel Thrane had a morale advantage over the other nations because its people are united by common belief, and by a faith that taught them to be ready to fight and to make sacrifices to protect the innocent.

- Thrane has the greatest access to divine magic on the battlefield. Unlike arcane magic, divine magic isn’t a science. As a result, it’s more mysterious, and mystery isn’t something you want in an enemy.

- Most of all: Thrane abandoned the monarchy to become a theocracy. That was undoubtedly terrifying to the leaders of all of the Five Nations — especially to Breland, where the monarchy is on thin ice.

Was Talenta pulled into the Last War at all, or was their relative distance and the influence of Ghallanda and Jorasco enough to spare them from most of the fighting?

The Talenta Plains are a large undeveloped stretch of relatively barren land; it’s got little that anyone actually WANTS, and virtually no cities or fortresses that could be claimed as strategic assets. The tribes have never assembled into what the Five Nations would consider an army. Thus they primarily are a path that Karrnath and Cyre passed through while fighting each other. If I was developing a full history of the war, I could certainly come up with some interesting events involving the Plains: interactions with the Q’barran colonists; interactions with Karrnathi forces planning a surprise offensive against the heart of Cyre; general interactions with supply lines, or the time Cyre decided to establish a fort there. But generally actions in the war would have involved raids, mercenary service (uncommon but possible), or defensive actions.

Forge of War indicates that of all the nations, only Karrnath didn’t ally with one of the other five at any point during the war. Do you agree with this?

It’s not my idea, to be sure. With that said, the Karrnathi character includes both deep confidence in the superiority of their own martial skills — a conviction that they are the greatest power in Khorvaire — and a bitter stoicism, they’ll have to kill us before we back down and even then our bones will rise and fight until they are ground to dust. So it seems unlikely to me that they wouldn’t have at least negotiated with Aundair regarding joint operations against Cyre, or the like (and I feel this has even been discussed in some other source), but I’m willing to accept the idea that Karrnath never engaged in a full if-the-war-ends-we-share-power alliance — that they always believed that they would either win the war and rule Galifar on their terms, or fight to the bitter, bitter end. This still can be seen in the present day, where many of the warlords consider Kaius’s strong support of peace initiatives to be a betrayal, a belief that drives many Emerald Claw recruits.

How common were sending stones and other Sivis communications equipment on the battlefield?

We’ve established that communications in Eberron are more akin to telegraph that to radio or phone. It wasn’t a modern battlefield where squads come be in direct real-time communication with one another. With that said, Sivis communication was a vital tool for long-term coordination. Speaking Stones are BIG and expensive; you’re talking about a wagon, and something Sivis wouldn’t want to put at risk in active battle. So you’d have such a thing with a major army, but not a unit. I can imagine a smaller focus device allowing a Sivis heir to send a message to or receive a message from the nearest speaking stone, but how I’d see it would be something requiring a ritual – maybe ten minutes, maybe more, along with expenditure of ground dragonshards – to activate, and likely that ritual has to be active to receive messages. So an heir could send an emergency message to the nearest stone if he had ten minutes to do it; but receiving messages is something he’d do at a specific time – check messages at noon – and not something that could be done in the midst of active combat. Of course, if you’re in a HUGE hurry, sending is an option – but there’s very few heirs who can do that.

So it was a vital tool for coordinating strategies and getting updates, but not real-time communication and not something the smallest units would have. With that said, I think you’d also see the Five Nations exploring other options – experimenting with Kalashtar psions, Aundair developing an alternate method of arcane communication, Vadalis messenger birds – but Sivis would be the gold standard.

Someone mentioned Karrnath doing necromantic experiments on living prisoners? That seems…beyond the pale for a salvageable nation state, to me. I don’t want to go that dark with Karrnath, but I’m curious about your take on that?

That someone was me. It’s part of the plot for an adventure I wrote for the ChariD20 event; the PCs are former Cyran prisoners of war who were used as fodder in necromantic experiments. A critical point here is that the adventure is about hunting the camp commander down in Droaam, because he’s a war criminal who’s fled the Five Nations. It’s not that Karrnath as a whole encouraged or engaged in such behavior; it’s that there’s ONE GUY (and his soldiers) who did so, and if he remained in Karrnath, KAIUS would have had him tried for war crimes. This ties to the difference between the Blood of Vol – a faith that uses necromancy, but generally as a positive tool that serves the needs of a community – and the Order of the Emerald Claw, which is about over-the-top pulp villainy and routinely engages in horrific actions. This commander is a pulp villain: a scenery-chewing mad necromancer that we all agree is a deplorable human and deserves to be brought to justice (whatever that ends up meaning).

So it’s not about KARRNATH being that dark. This is an example of what the Order of the Emerald Claw is capable of, and it’s WHY the Order of the Emerald Claw is considered a terrorist organization; again, if the villain here remained in Karrnath, he’d have been brought to justice for his crimes.

My player is under the impression that Karrnath was not doing as well as they had, toward the end of the war, and may have started experimenting on people out of a bit of desperation. My impression was that… they were still in a strong position when the war ended, other than the famines.

Karrnath has always been struggling due to famine and plagues. They turned to use of undead in the first place as a way to offset this. However, Kaius chose to break ties with the Blood of Vol and limit the use of necromancy towards the end of the war, as opposed to embracing desperate measures. The main issue is that at full strength one would have expected Karrnath to steamroll Cyre; instead, because of their troubles, it’s been more even. But it’s still a force to be reckoned with, and many warlords are angry at Kaius for pursuing peace because they believe Karrnath is still strong enough for war. As a side note, in my Eberron Kaius blames the famines and plagues on the Blood of Vol, giving him a populist platform to strengthen his position; thus Karrnathi Seekers are dealing with prejudice and anger, which is further exacerbated by the actions of the Order of the Emerald Claw.