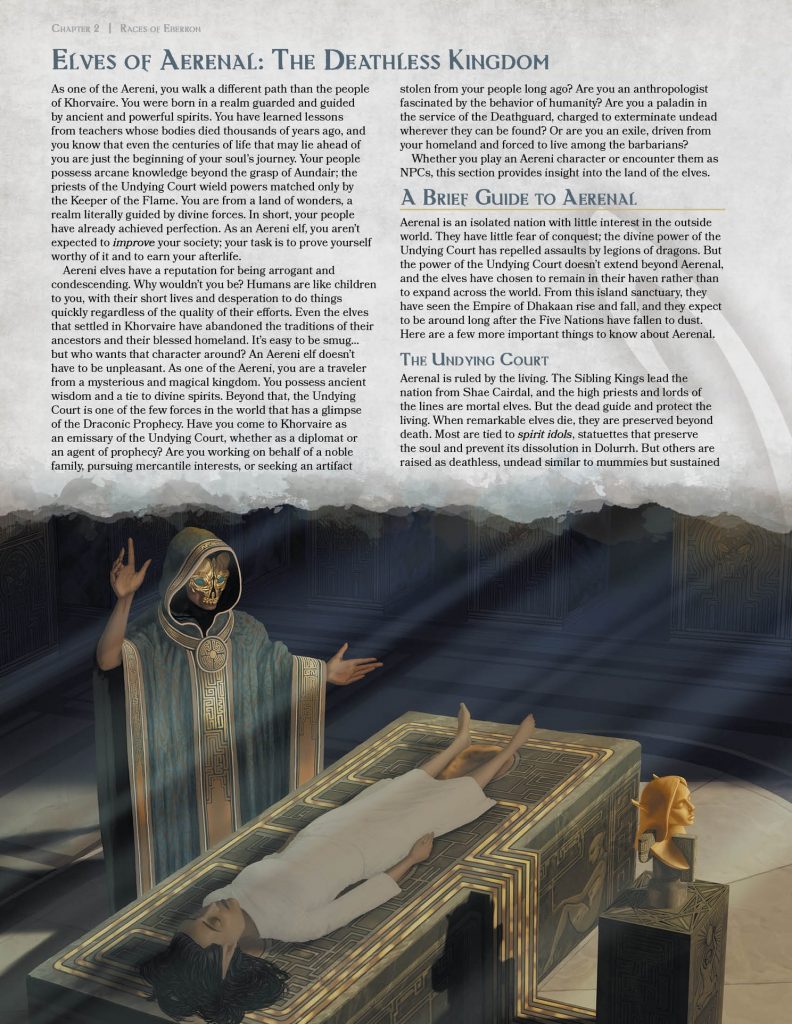

While I’m dealing with deadlines, I’ve reached out to my Patreon supporters for questions that can be addressed in short articles, and I’ll be addressing these as time allows. To begin with, I want to take a quick look at the Elves of Eberron.

Elven civilization began on Xen’drik. It’s said that the giants sacked one of the great Feyspires of Thelanis, severing its ties to the Faerie Court and scattering and enslaving its people—and that over generations, these refugees became the elves. Many elves served as slaves of the giants, and this continued for thousands of years. But when the conflict with the Quori weakened the nations of the giants, the elves rose up against them. This was a long and bitter struggle fought over the course of generations. The elves lacked the resources or raw power of the giants, and couldn’t face them in the field; for the most part it was driven by guerrilla war, with heroic bands of elven champions striking against the giants and disappearing into the wilds. The Sulat giants created the Drow to hunt the elves, following them into places giants couldn’t go. There was never a point at which the elves truly stood a chance of defeating the giants, but the escalating cost of the war (both financially and in lives) eventually became unbearable. The Cul’sir giants prepared to unleash devastating, epic magic against the elves—magic on the same scale as they’d employed against the Quori, forces that destroyed a moon and threw a plane off its orbit. And in so doing, they went too far. The dragons of Argonnessen didn’t care about the elves, but they would not allow the giants to threaten Eberron itself. Flights of dragons devastated Xen’drik—giant and elf alike—and employed epic magics to ensure that no great civilization would ever rise again in the shattered land.

The prophet Aeren is known not for their deeds during the war, but for foreseeing how it would end. Aeren gathered together elves of many different clans and traditions, and convinced them to abandon Xen’drik and escape this coming apocalypse. This rag-tag fleet eventually reached a massive island, but Aeren did not survive the journey. Aeren was interred in soil of the new land, which was named Aerenal—”Aeren’s Rest.”

One of the key points in understanding the elves is that the description of their history is often simplified.The common story is Elves were enslaved by giants. Elves rebeled and eventually fled. The mistake is in thinking that “elf” and “giant” describe singular, monolithic cultures—that ALL elves were slaves of the giants, or that “the giants” were themselves a single monolithic force. Neither of these things are true. The giants had three major nations—the Sulat League, the Cul’sir Dominion, and the Group of Eleven—along with many lesser nations. There were elves who labored as slaves of the giants, but there were others who were never directly under giant rule. The Qabalrin elves maintained a city-state in the Ring of Storms that was a match for even the Cul’sir; it was destroyed not by giants, but by the cataclysmic fall of a giant Siberys dragonshard. The ancestors of the Tairnadal elves were largely nomadic tribes, fleeing further into the wilds as the giants expanded. The “Elven Uprising” involved an alliance of the nomadic tribes, seeing the vulnerabilities following the Quori conflict, combined with an internal uprising and acts of sabotage among the slaves. It was vast and long, fought on many different fronts and between many different nations, and was properly less a war and more an extended period of upheaval. It’s quite possible that the giants themselves fought one another during this time; it may well be that the Sulat League created the Drow not merely to hunt other elves, but also to strike against rivals in the Cul’sir Dominion.

The point is that the elves that followed Aeren were drawn from different nations and traditions. The elves now known as the Aereni were largely those enslaved by the giants, while the Tairnadal are descended from the nomadic warriors. This is one reason that the Aereni have a stronger arcane tradition (inherited from their giant oppressors) while the Tairnadal have a stronger role for druids and rangers. Meanwhile, the line of Vol could trace its roots back to the Qabalrin, and clung to some of their necromantic secrets. Aeren’s vision united them, but with Aeren’s death they split apart… and each pursued their own path to ensure they never lost their greatest champions. The Tairnadal preserve their heroes by serving as mortal avatars for their spirits. The Aereni learned to use the Irian manifest zones of Aerenal to create the deathless, preserving their greatest champions as positive undead; as it took thousands of years to accomplish this, it was far too late to use these techniques on Aeren. And the line of Vol and its allies perfected their techniques of Mabaran necromancy, preserving their greatest as vampires, liches, and mummies. A bitter rivalry built between the Aereni and Vol, culminating in the utter destruction of the Line of Vol—a conflict justified by their attempts to perfect the Mark of Death. Meanwhile, the Tairnadal and the Aereni have continued to exist side by side, following different paths without hostility.

If you’d like to know more about any of this, here’s a number of articles:

General Q&A

GENERAL QUESTIONS

In general, Darwinian evolution doesn’t play a major role in Eberron. How did the eladrin become elves?

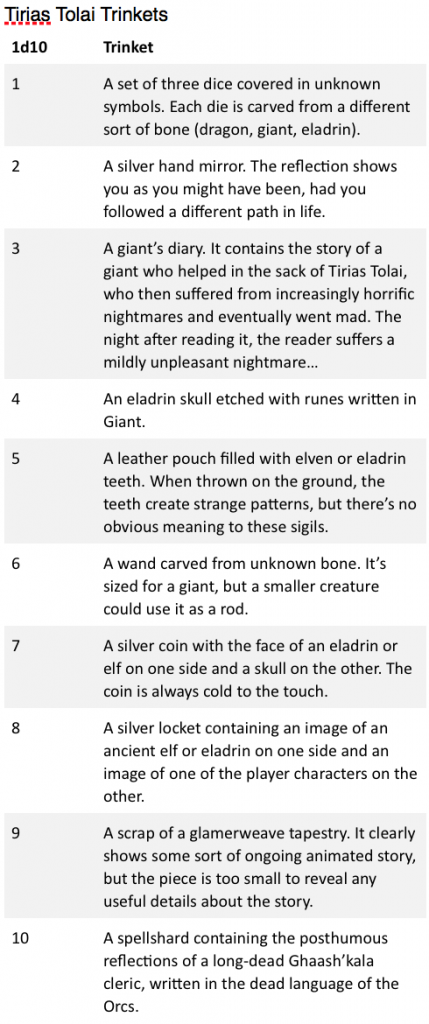

The ancestors of the elves were the eladrin of Shae Tirias Tolai, and they didn’t become elves through a process of natural evolution. When the giants sacked the Feyspire, they did something to prevent the Eladrin from escaping. Remember that the giants wielded epic level magic and have been shown on multiple occasions to be able to sever planar bonds—on a small scale with the Citadel of the Fading Dream, and on a larger scale with Dal Quor itself. So they somehow severed the eladrin from Thelanis. We don’t know exactly what they did, but the result was that the children of those surviving eladrin were born as elves.

Due to the conflict of lore regarding Aeren’s pronouns between the Dragonshard (and 4E Eberron Campaign Guide) and Magic of Eberron, would it be plausible to say they’re both right, in a way, and that Aeren was genderfluid?

Sure! That seems entirely plausible. With that said, there’s a few larger issues with the MoE depiction of history. It focuses solely on those elves enslaved by the giants, and depicts the entire struggle as being about escape from Xen’drik. It’s depicted as a prison break on a massive scale—”But secrecy… was vital, lest betrayal ruin all their years of hidden labor.” There’s no mention of the active conflict between elves and giants, the struggles that established the legends of the Tairnadal ancestors. Compare this to the original ECS description of the Age of Giants…

The remaining giant kingdoms never quite recover from the events of the quori invasion. Horrible curses and plagues sweep through the land, and the elves use the opportunity to rebel. In desperation, the giants again turn to the same magic they used to stop the quori. Before they can unleash such destruction a second time, the dragons attack. Giant civilization crumbles, the drow go into hiding in the Xen’drik countryside, and the elves flee to the island-continent of Aerenal.

By contrast, Magic of Eberron says nothing about giant civilization being crippled from the quori conflict. It doesn’t present an active war between elves and giants, the conflict that gave birth to the patron ancestors of the Tairnadal. The rebel elves launch a single massive attack and then immediately flee. There’s no mention of the Tairnadal and no mention of what causes the apocalyptic attack of the dragons. It’s fairly easy to resolve this; look to the MoE account as describing sabotage going on within the Cul’sir Dominion at the same time as the Tairnandal attacks, and something that further pushed the giants to that point f desperation. But the point is that the rebellious elves weren’t originally planning to flee; Aeren is noteworthy for foreseeing the actions of the dragons and for bringing together elves of many traditions—not just the Cul’sir slaves—and convincing them to join the exodus.

Magic of Eberron then goes on to say that Aeren became the first of the deathless, developing the techniques while on Xen’drik. The other canon sources maintain that the rituals required to develop the deathless were developed on Aerenal thousands of years after the exodus, in part because they required the powerful Irian manifest zones in that land and in part because this work was driven by the loss of Aeren—and a determination never to lose so great a soul again.

TAIRNADAL AND VALENAR ELVES

What do the Talenta halflings and the Valenar elves have to fight about? They’re both pastoral herding cultures separated by an inhospitable desert. Numerous sources mention Valenar incursions looking for a good fight. I understand why players would want to deal with a culture like that, but why would a culture encourage it on one side, and the other side, not discourage it ‘with extreme predjudice’?

It’s a mistake to think of the elves of Valenar as a “pastoral herding culture.” They are an army, in Khorvaire for the sole purpose of fighting a war that has not yet begun.

As described above, the ancestors of the Tairnadal fought against the giants of Xen’drik. It was a daring conflict against impossible odds, but through remarkable skill, strategy, and cunning the elves won remarkable victories and ultimately drove the giants to the rash actions that brought about their doom. Later the Tairnadal came to Khorvaire, where they fought the Dhakaani goblins at the height of their power. Once again, the elves performed heroic deeds in battle against an overpowering foe. In the end, they weren’t defeated; they were forced to retreat from Khorvaire to run towards an even greater battle, fighting the dragons that were attacking their homeland.

The Tairnadal elves are driven by these ancient conflicts. They believe that every Tairnadal elf is chosen by the spirit of a patron ancestor, a legendary hero tied to these wars with the giants, goblins, or dragons. The mortal elf serves as an avatar of the ancient hero. The more closely the elf emulates the ancestor, the stronger this bond becomes. This is both a duty—preserving the spirit of the ancestor from being lost to Dolurrh—and a privilege, as they believe that through the bond the elf inherits the skills and wisdom of the ancestor. And the greatest aspiration of all is to perform such glorious deeds that the living elf will be venerated as a patron ancestor by the generations yet to come.

The Tairnadal made a pledge to Dhakaan, a promise that they would not return to Khorvaire in force unless invited. During the Last War, Cyre issued that invitation. The elves didn’t come to Khorvaire because they wanted land in which to herd horses. They didn’t come because they wanted or needed the wages Cyre was paying them. They returned in search of a glorious battle, a conflict that would allow them to match the deeds of their ancestors. But they soon concluded that their work as mercenaries wouldn’t give them that. So Shaeras Vadallia seized what is now Valenar as an intentional provocation. Since the Treaty of Thronehold, these Valenar elves have been breaking the terms of the treaty and raiding their neighbors. Why? In part it’s to keep the skills of their warriors fresh. In part it’s because the members of those individual warbands seek opportunities to strengthen their bond to their ancestors in battle. But most of all, it’s because the elves want someone to attack them. Their ancestors weren’t conquerors or mercenaries; they were guerrilla warriors fighting against an overpowering foe. The Valenar want to provoke a mighty enemy—perhaps Karrnath, or a resurgent Dhakaan—into attacking them in Valenar. As elves, they are perfectly happy to wait a century for this plan to play out, and in the meantime they are learning the lay of the land in Valenar, finding ambush points, laying traps. The Tairnadal don’t care about Valenar as a colony; for them it’s a killing ground, and they are just kicking hornet’s nests and waiting for someone to take the bait.

So why raid the halflings? Largely, because they’re there. The Valenar forces in the Talenta Plains aren’t acting on Vadallia’s orders. These warbands are self-sufficient units sent off on their own recognizance. They are searching for worthy foes and violating the Treaty of Thronehold… again, provoking the other nations. These warbands aren’t primarily interested in plunder, and they generally avoid attacking civilian populations; whenever possible they are looking for WORTHY opponents. They’re also attacking swordtooth titans and other deadly dinosaurs. And some are even crossing the Plains to launch attacks into Karrnath… as that’s one of the forces they’d really like to provoke to attack Valenar.

For their part, the halflings have no interest in conflict with the Valenar. The tribes are only loosely aligned and aren’t driven by war. They seek to defend themselves against raiding warbands, but they aren’t prepared to go to war with Valenar. Now again, for this very reason, this is why the Valenar AREN’T particularly interested in fighting the halflings. They provoke them in order to try to draw out their best warriors and hunters, to try to have a challenging fight. But they would RATHER battle the full might of Karrnath, or something similar. The halflings just have the misfortune of being between the two.

So in part, bear in mind that the Valenar elves aren’t a culture as such; they are a Tairnadal army in the field, biding their time as they wait for a more powerful foe to take the bait and attack them in Valenar.

Do the Tairnadal take the namesake of the ancestor they emulate?

Many do, though not all. For example, High King Shaeras Vadallia is an avatar of Vadallia, who was described in the Eye on Eberron article in Dragon #407. But it’s not a requirement, and some consider it to be pretentious.

Are the Tairnadal ancestor spirits literally biological ancestors of the elves that they choose? Or is it more of a cultural line of descent?

It’s more of a cultural line of descent. As noted in the previous question, Tairnadal families are very fluid to begin with. Plus, the original ancestors lived around forty thousand years ago. The lifespan of an elf is about ten times that of a human; can you trace your ancestors back four thousand years? So it’s largely assumed that MOST Tairnadal are related to many of the patron ancestors, and there’s no particular fear of a bloodline dying out. UNLESS, of course, that’s a story you want to explore in your campaign!

Tairnadal ancestors choose their heirs – Why do they pick who they pick? Can there be conflicts between multiple ancestors for one heir?

By default, the patron ancestors move in mysterious ways, and mortals don’t get to know the answers to these questions. It’s up to you as a DM to decide if you want to personify the ancestors more concretely and allow PCs to find these things out. In one campaign I DM’d, one of the PCs was a Valenar ranger. His idea was that he always believed he was going to be chosen by a legendary swordsman, and he’d instead been picked by a champion archer. Furious, he’d stolen the blade of his ancestors and deserted, determined to find his own path… in spite of the fact that he had a bond to the archer and couldn’t force a bond to the swordsman. While we never completed the campaign, the idea of the story was to explore whether he would eventually choose to embrace the archer… or whether he could find some way to change his stars and forge a bond to the swordsman. Had this continued, it would have likely involved a deeper interaction with the spirits themselves and an exploration of why the archer chose him.

It’s also been mentioned that ancestors are chosen for the elf, not by the elf. I’d assume there are some cases of rejection among them, elves who do not want to follow this particular ancestor for whatever reason. What do the Valenar do about these cases?

See the previous answer! This is covered in detail in this article under the heading “Why Should I Do It?” Bear in mind that it’s not that your ancestor is chosen for you, it’s that you are chosen BY an ancestor. The spirit of a champion of legend says “This one’s mine.” You are a soldier in an army being given a command by the highest authority, and you’re a follower of a religion devoted to honoring these spirits. But yes: this means that you could be someone who believes in honor and chivalry, and then you could be chosen by the Butcher and told you must not only be ruthless and cruel, but you must do your best to EXCEL at it. If you say no, you’re a soldier refusing a command and an acolyte turning your back on your faith. So you can expect to be discharged from the army—which means being severed from your culture—and shunned by former people.

In short, it’s a great path for a player character who needs to explain why they are out adventuring instead of serving with a warband. Will you reconcile and accept the spirit that chose you? Will you find a way to forge a bond with a different ancestor? Or will you remain an outcast?

Are there any actions the Valenar do not tolerate in warfare? Things they would consider war crimes? If their patron ancestor would do things considered by society to be immoral, even in war, would they share any of those views?

The Valenar believe it is their duty to emulate the patron ancestors. If you compare it to the Sovereign Host, some of the ancestors are more like Dol Arrah, some closer to Dol Arrah, and a few could be compared to the Mockery. The elves of Xen’drik fought a guerilla war against a vastly superior foe, and there were many who relied on cunning, deception, and terror to accomplish their goals. So there are Valenar who believe in absolute chivalry and honor on the battlefield, and there are ruthless Valenar feel that deception and terror are necessarily tools—who feel they have a religious duty to strike fear into their foes. The point is that a Valenar commander KNOWS what behavior to expect from their troops. They’ll use the Dol Arrahs on the open battlefield, and they’ll use the Mockeries as commandoes and skirmishers… and they definitely won’t put the two side by side. The honorable Valenar are disgusted by the butchers, but they know that the butchers are required to be butchers.

So for example, MOST Valenar won’t kill civilians. But there are then there are a few who will specifically target civilian populations, because that’s something their ancestor was known for doing. The commander knows this, and won’t put that unit in the field unless that’s what they expect of them.

Three subgroups of Tairnadal have been described. The Valaes Tairn believe that glory in battle is the highest goal, regardless of the nature of the foe. The Silaes Tairn are determined to return to Xen’drik and reclaim the ancient realm of the elves, and the Draleus Tairn wish to destroy the dragons of Argonnessen. Do Tairnadal elves choose which group to be in or do they all grow up and stay with their group?

The Valaes Tairn are by far the largest of these three groups. They also receive the most attention because they’re the only ones who generally come to Khorvaire. The Silaes are focused on Xen’drik, and the only reason for a member of the Draleus Tairn to come to Khorvaire is a dragon hunt… and the dragons of Khorvaire generally keep a very low profile.

The first and primary factor in which group you follow is your patron ancestor. If your patron is a legendary dragon hunter, you’re likely to join the Draleus Tairn. Otherwise, the default is the Valaes Tairn, but it’s largely about what you feel your patron ancestor is calling you to do, which is something you might discuss with one of the Keepers of the Past. If you have the support of a Keeper, people will respect your decision.

Bear in mind that you won’t generally “grow up” with one of these groups. They’re all essentially military units, and until you’ve reached adulthood and the Keepers have identified your patron ancestor, you’re essentially not equipped to travel with a warband.

Why aren’t the Silaes Tairn the major sect? Obviously, dragon-slayer heir would want to fight dragons, but aren’t the majority of the ancestors giant-slayers (or drow slayers)? And are the Valaes Tairn the largest sect historically?

Because Xen’drik is a cursed ruin; the giants and the drow aren’t the same as those the ancestors fought. The Valaes Tairn believe that it doesn’t matter WHAT you fight or WHERE you fight; what matters is that you act as your ancestor would act if they were in your place. This is inherently more flexible, and that’s why it’s the most widespread belief. Someone who’s ancestor is legendary for fighting drow COULD feel drawn to the Sileus Tairn, because they want to fight drow; but they could easily say “What defines my ancestor is her courage and her techniques for fighting multiple enemies at once, and I can demonstrate both of those fighting goblins.” Essentially, most see the Silaes Tairn as slightly crazy extremists; the Valaes are the most moderate sect.

ELVES OF KHORVAIRE

What are the religious views of the elves of House Phiarlan? Did they follow the path of Vol, the Undying Court, or the Tairnadal? Do they still follow these traditions?

Excellent question. This is covered in this Dragonshard article. Here’s part of the relevant text.

The houses of shadow can trace their roots back to the Elven Uprising, the ancient war between the giants of Xen’drik and the ancestors of the modern elves. Many assume that this was a conflict between two monolithic entities, but neither elves nor giants were unified forces. Many different giant nations existed, and there were dozens of sects of elves, ranging from former slaves to guerillas who had fought the giants for millennia. Over the course of the uprising, some elves served as liaisons between the many different tribes. These travelers saw their role in war as being more spiritual than physical: Their task was to uphold morale and maintain the alliances between the scattered soldiers. They called themselves phiarlans, or “spirit keepers.” These phiarlans learned the traditions and customs of all elven sects, and a phiarlan bard could inspire warriors from any tribe. The phiarlans were not generals or military strategists, but their motivational work and the intelligence they carried from place to place was an invaluable part of the military effort.

The article goes on to describe how the Phiarlans continued to serve this role in Aerenal—serving as envoys and mediators for elves of all lines and cultures. In essence, they acknowledged and understood all of the traditions, but they never fully embraced them. A Phiarlan bard knows the stories of the Tairnadal ancestors, but doesn’t seek to embody an ancestor. And looking to the Undying Court, the Phiarlans acknowledge that exists, but they turned their back on it when they left Aerenal; they don’t believe it watches over them and they aren’t aspiring to join it.

Overall, the elves of the House of Shadow typically aren’t very religious. They seek to understand all faiths but rarely commit to one. There are some who embrace the Sovereign Host or the Dark Six, but in general they are a pragmatic people devoted more to their work and their traditions than to abstract forces.

Is there a particular culture and history for Khorvaire elves among other regions, such as in cities or the Five Nations? How did it come to be that those elves left their Valenar and Aerenal roots, to the point that half-elves were in large enough numbers to be considered their own distinct race (Khoravar)?

As the Undying Court rose to power, there were always elves who opposed it and chose to leave Aerenal to explore other opportunities. There was a greater wave of migration following the eradication of the Line of Vol. The Vol bloodline was the only one that was exterminated; her allies had to choose exile or to swear oaths to the Court, and many chose exile. While others, like the Phiarlans, were disturbed by the conflict and left of their own accord. That was 2,600 years ago. So there are places like House Phiarlan and the Bloodsail Principality where elves maintain a unique culture, but many of these immigrants fully integrated into their nations. A typical Brelish elf is Brelish first, elf second. Elves in Thrane are likely to be devoted to the Silver Flame; it’s just that an elf elder devoted to the Flame might have personally known Tira Miron. But the short form is that elves in Khorvaire could trace their roots back to followers of Vol or immigrants driven by curiosity, but for most those roots are long buried and they have assimilated into the local culture.

Meanwhile. the reason half-elves are considered their own distinct race is because they ARE their own distinct race. Most Khoravar are children of Khoravar, and their original elven ancestors could be buried so deeply in their family trees that they don’t even know who they were. Khoravar are more fertile than elves, and so over the course of thousands of years, they’ve spread more rapidly.

Do elves still constitute a sizable portion of the Blood of Vol’s faithful and if so do they have a different take on the religion as they are only a few generations separated from the initial mixing with humans in Lhazaar?

It’s important to recognize that the religion known as “The Blood of Vol” was never practiced by the line of Vol. This is a critical point about Erandis, because she doesn’t follow the faith. The Blood of Vol is a religion that emerged over the course of centuries, inspired by the words of Vol’s allies who settled in the Lhazaar Principalities, but interpreted and adapted by the humans… and then continuing to evolve as it traveled into Karrnath, which became its heart. So no, elves don’t constitute a sizeable portion of the Seekers. Some of these refugee elves fully integrated with the cultures they joined. The place where they’ve held to their traditions—and where they still practice the ORIGINAL teachings of the line of Vol—is in the Bloodsail Principality in Lhazaar, based on the island of Farlnen. The Bloodsails were described in detail in the Eye on Eberron article in Dragon 410.

With that said, it’s been more than just a few generations. An elf can live up to 750 years, but by the 3.5 tables they are considered “Venerable” — the most extreme age category — at 350. It’s been 2,600 years since the line of Vol was wiped out. If we set the generational length at 350 (which is somewhat generous, as the human equivalent of venerable is 70, but we typically set human generations at around 25), we’re still talking over seven generations. The issue is that in following the traditions of Vol, Farlnen is home to many vampires and liches who have unliving memory of the past and maintain those ancient traditions.

If you have questions or thoughts about the elves of Eberron, post them here!