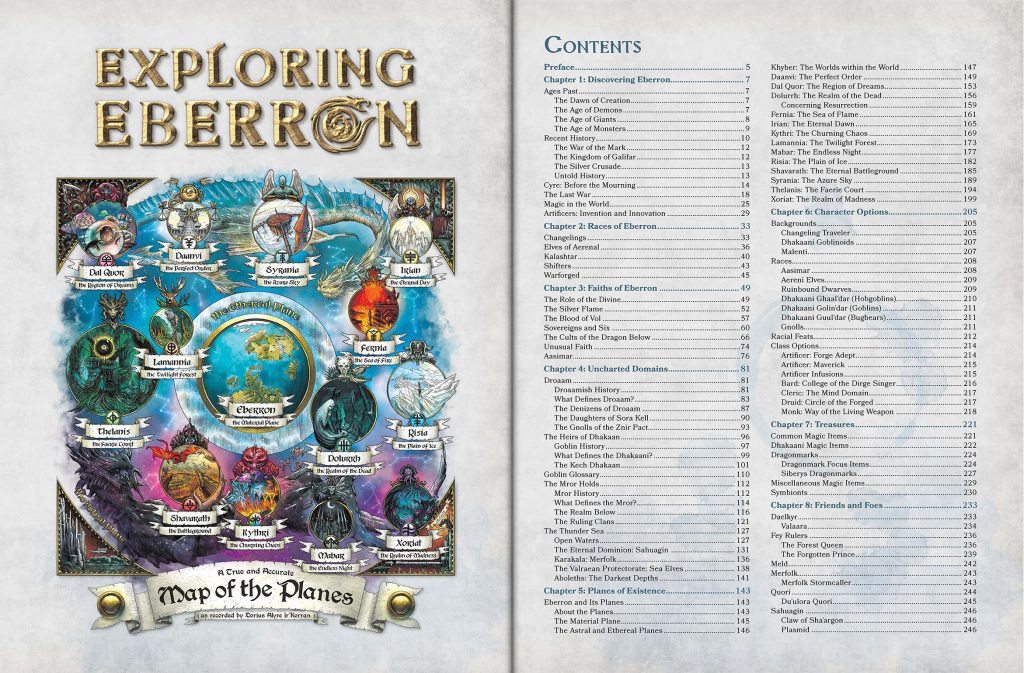

My new book Exploring Eberron is available now on the DM’s Guild. You can find a FAQ about it here. Yesterday I posted an IFAQ about developing languages. In the comments, a question came up about the role of the Elvish language in the world. Since the answers have broader implications on a general philosophy of worldbuilding, I wanted to make it a standalone IFAQ. So…

Elvish is the language of Thelanis. Is that primordially true, i.e. did Elves speak that language prior to their enslavement by the Giants? Also, if Elvish is the language of Thelanis, are Elves born knowing it, or must it be taught to children like any other language?

There are no canon answers to these questions. By the rules of D&D, elves speak Elvish. It’s part of their racial features. There’s no explanation of where the language came from or how they come to learn it. So first, to be clear, everything I’m about to say is what I do IN MY CAMPAIGN. It has no foundation in any canon source, though as far as I know it doesn’t contradict any canon source either; the topic has simply never come up. But if you don’t like it, don’t use it. To me, this is a perfect example of a choice where you need to think about the broader implications—you need to be sure you WANT your story to go down a particular path. So I’ll tell you my answer, but then I want to talk about WHY I’d answer that way.

First: Elvish is the language of Thelanis. That is primordially true. The planes are universal concepts, and their fundamental principles don’t change (setting aside the complications of Dal Quor!). With that said, one of the minor effects of Thelanis is that while you are in Thelanis, you understand Elvish. When you’re wandering through the Endless Weald, you can understand the songs of the dryads singing in the trees; you are part of the story and that means you understand its words. It is only when you and a dryad LEAVE Thelanis that you realize that you can’t understand her any more, and start hearing her words as Elvish instead simply understanding their meaning.

Second: In my Eberron, every elf is born with an innate understanding of the Elvish language. It doesn’t matter if you’re an orphan born in a Sharn gutter or a proud Aereni. You don’t have to be taught; the language a part of you, tied innately to the Fey Ancestry feature. It is impossible to be an elf and NOT understand Elvish.

WHY DO THIS? What appeals to me about this is that in concretely establishes that elves are not human. They aren’t just humans who have pointed ears and live for centuries. They are fundamentally alien beings whose minds do not work the same way as human minds. It further reinforces other things we’ve established about the elf cultures, namely that they are extremely tied to tradition and that they aren’t as innovative as humans. This makes sense if elves have a greater degree of engrained knowledge and instinct than humans. As an elf, you never have to develop a new language. You are born knowing THE LANGUAGE, the language that will allow you to speak to any elf anywhere.

This comes back to one of my basic principles of world building. I like exploring worlds that are unlike our own. To me, it’s fascinating to consider the impact of having a language seared into your brain from the moment of birth. How would that affect the development of culture? It is fundamentally the antithesis of the Babel story—the people of the world are divided by their many languages, but all elves are united by their common tongue.

The original question included this: was Giant the language that the oppressed elves were supposed to use with their overlords, while Elvish was preserved as the language they used among themselves? Absolutely. The giants weren’t going to learn Elvish, so elf servants had to learn at least basic Giant. It’s not that Elvish was preserved, because the elves couldn’t forget it even if they wanted to. But it was unquestionably SUPPRESSED, and elves would be punished for speaking it. But this is also a crucial factor in the eventual uprising. Captives of the giants, descendants of Qabalrin refugees, the unconquered ancestors of the Tairnadal—despite their different cultures and histories, they were united by the Elvish tongue and could always understand one another. Given this, one might well ask what about the Drow? First of all, by the RULES drow speak Elvish. Second, they possess the Fey Ancestry trait. To me, those two facts hold the answer. While altered by the giants, the drow still have their Fey Ancestry, and it is through that ancestry that they know the Elvish language.

This gets to a much deeper and more complicated question: Do the Khoravar (half-elves) innately understand Elvish, or do THEY have to learn it? The reason this is complicated is because it has vast ramifications on the relationship between Khoravar and Elves. We’ve often raised the question can a half-elf become a Tairnadal? Could they join the Undying Court? If all elves innately understand Elvish and Khorvar do NOT understand Elvish, that’s a deep point in favor of the idea that Khorvar are fundamentally not elves… while if they are born with the knowledge of Elvish, that’s a strong argument that they ARE spiritually part of the elf species and COULD connect with Patron Ancestors. PERSONALLY, I would say that Khoravar DO innately know Elvish, for the same reason as drow. Under the rules of 5E, half-elves possess the Fey Ancestry feat and have Elvish as an ingrained language. For me, it’s all about that Fey Ancestry; part of what it means to have Fey Ancestry is to KNOW ELVISH, in the same way that I’ve said that part of being a druid is that you KNOW DRUIDIC. This also explains why the Valenar were so quick to bring in Khoravar administrators; they may not consider them equals, but it’s good to have an administrator who KNOWS THE LANGUAGE. But this is definitely a case where I could see a DM ruling the other way specifically because of how they want to play out that story of the Khoravar who wants to be Tairnadal. We’ve also made a point of saying that many Khoravar communities develop a Khoravar Cant that is a unique blend of Elvish and Common; part of the point of this is that they KNOW Elvish, but they are choosing to speak in a manner that is unique to THEIR people, not simply relying on the language of either parent. Likewise, it adds color to the relationship between Aereni and drow; even though the drow were created to kill elves, they still know the Language.

So this raises another interesting question… what happens when you need a new word? A situation arises where there’s a concept that’s never been expressed in Elvish, or a poet is expressing an entirely new concept. Do they create a new word? If so, wouldn’t they have to teach it to others? Isn’t this exactly how we end up developing unique dialects and new languages? Certainly. But this is where we get back to the point that they’re not human, that they are touched by the Fey, that this is something that fundamentally doesn’t make sense. The poet doesn’t create a new word the way a human poet would. They realize they already know the word, even though it’s never been spoken in Elvish before. And once spoken, every other fey creature also knows that word. Because Elvish isn’t just a mundane, mortal language; it is an immortal, magical language. An elf knows Elvish because fundamentally, they are fey, and being fey means knowing Elvish. The language evolves as it is needed, and all fey creatures know the language. What this DOES mean is that any creature without Fey ancestry who learns Elvish WILL find that new words occasionally appear and they’ll have to learn their meaning, because without Fey Ancestry, they don’t get those automatic dictionary updates.

This is a long discussion of a point that, mechanically, makes no difference. Because by the rules, elves just know Elvish. It’s a racial feature with no inherent story. But the point is that once you add a story you GIVE it meaning. The reason I’d say that they DO all know it, that it is fundamentally tied to Fey Ancestry is because I WANT to explore the impact of that decision—on the Xen’drik Uprising, on the relationship between Khoravar and Aereni, on the idea of elves being bound to tradition. I think it’s interesting to explore ways in which elves AREN’T like humans, and to imagine what it would be like to be born with immediate, perfect knowledge of a language.

So, in conclusion, when there is no canon answer to questions like this—or even if there is!—the question to me is always how will it affect the story, and what story do I want to tell? *I* find the story of innate-knowledge-of-Elvish more INTERESTING that Elvish-is-just-a-mundane-language-like-any-other. But you certainly don’t have to agree with me!

Are there other languages that would work the same way?

Certainly. I’d say that an aasimar understands Celestial the same way that an elf understands Elvish; they don’t have to learn it, and you can’t be an aasimar and NOT understand Celestial (unless you’re an aasimar tied to a power that speaks another immortal language; note that the Court aasimar in Exploring Eberron speaks both Elvish and Celestial, and of course has Fey Ancestry!). All true immortals are born innately possessing all of their basic knowledge, including languages, and I would say that just like I’ve suggested with Elvish, if Celestial needs a new word, all creatures with an innate knowledge of Celestial automatically know that word. Again, MORTALS who have LEARNED the language wouldn’t get that automatic update. This could be an interesting element for archaeologists, being able to date inscriptions in Abyssal or Celestial based on “Note the use of ‘Alael’, which didn’t become part of the language until the Age of Giants.” But in general this would be an aspect of immortal languages. Humans can make new languages; immortals are born knowing their language, and again, can usually make themselves understood when they wish to.

In this article I suggested that Undercommon might be constantly evolving, but that anyone who could speak Undercommon automatically knows the current form of it—essentially the same principle as the Elvish dictionary updates, but that rather than just ADDING to the existing language, the pre-existing words are always changing… and that when you find inscriptions in Undercommon, they may make no sense under the current form of the language or they might have taken on a new meaning. However, this is a pretty difficult concept for us poor mortals to wrap our brains around, and I didn’t actually push it in either the Wayfinder’s Guide or Rising From The Last War.

Before the fall of Xen’drik were there multiple Giant languages for each realm?

This comes back to the whole question of language-in-games in general. Xen’drik is a massive continent and there were multiple, very distinct giant civilizations. Barring some exterior factor—IE Fey-Ancestry-means-you-speak-Elvish—it’s reasonable to assume that these different giant cultures would all have developed unique languages. However, it’s also the case that we haven’t defined those languages; we’ve never mentioned Sulatan or Elevenese. What we’ve said is that the language we know as Giant was the COMMON TONGUE of Xen’drik, widespread enough that it is what you find spoken by the vast diverse range of creatures across the continent. I might very well introduce the idea of Elevenese as a PLOT DEVICE—the adventurers have found an ancient scroll in Risia that’s written in old Elevenese, the pre-Giant language of the Group of Eleven! It’s completely unknown in the modern age, and you’ll need to use Comprehend Language!—but I’m not going to expect a player character to waste a language slot learning Elevenese; Giant is the language you NEED to know to get by in Xen’drik. Again, at the end of the day, it’s the question of how will this decision affect the story you and your friends tell at your table?

What is the difference/relationship between Celestial and Draconic?

In the article that’s been linked a few times I suggested that they might be the same, but I’ve actually backed off from that (and we didn’t include it in Rising From The Last War). I think that there are SIMILARITIES between the two, just as I’ve suggested that Goblin and Orc may have their roots in Abyssal (noting the similarity between Goblin and the names of the Overlords). But essentially, I think Draconic is the oldest MORTAL language, but it’s not an IMMORTAL language.

What about gnomes? Aren’t they fey? Do they know Elvish?

The idea that gnomes are from Thelanis was added into the fourth edition books specifically to address the fact that in fourth edition Dungeons & Dragons, gnomes were fey creatures. This is no longer true in fifth edition, and it’s not something we mention in Rising From The Last War. To my mind, this is in the same category as BAATOR, which was added into the planar cosmology in fourth edition, and REMOVED AGAIN in Rising From The Last War. Canon can evolve, and the latest canon does NOT have gnomes as Thelanian immigrants. What I have suggested is that there are gnomes who have immigrated FROM EBERRON TO THELANIS through the Feyspires, but they are natives of Eberron. They do not have Fey Ancestry and as such don’t have an innate understanding of Elvish. If a gnome knows Elvish, it’s because they learned it like anyone else.

Setting aside the fact that the idea of gnomes being from Thelanis was always a 4E artifact, the gnomes and elves of Eberron have a few very fundamental differences that reflect this. The elves are deeply bound to tradition and not driven toward innovation. They are happy to exist in isolation. By contrast, gnomes are typically extremely inquisitive. They are called out as being explorers, seeking out new lands and discovering new cultures. The Zil try different religions. House Sivis is specifically called out as having created multiple languages. They’ve reverse-engineered elemental binding techniques recovered from Xen’drik. The fact that there’s some gnomes in Thelanis is a reflection of that deeply inquisitive nature—not of Thelanian origins. With that said, as I describe in the Exploring Eberron FAQ, I’m playing a gnome artificer from Pylas Pyrial in my current campaign. But he’s NOT a fey creature; he’s just using the “Magical Thinking” style of artifice tied to his Pyrial upbringing.

Thanks for taking this deep dive into the Elvish rabbit hole. And thanks to my Patrons for making it possible!

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon