To view this content, you must be a member of Keith's Patreon at $5 or more

Already a qualifying Patreon member? Refresh to access this content.

The warforged captain stared at the great orange orb ahead of them. “This is it, my friends. We are about to be the first people to set foot on Olarune. Thanks to your courage and your tireless efforts, we will bring honor to Breland—and Sovereigns willing, profit.”

“Captain, ship ahead!”

“Impossible. “ The captain adjusted his ocular lenses. “We’re a day ahead of the Karrns—”

“It’s not the Blade. It’s an unknown design, sir. And it’s ascending from the surface.”

The deck crew ran to the rails. The approaching ship was like nothing they’d ever seen; it looked like a great oak uprooted and cast into the air, with tapestries of rainbows spun between its branches. In its own way, it was beautiful. But as it drew closer, the crew of Intrepid heard the sounds coming from it—the howls of hungry wolves.

Spelljammer intertwines fantasy and magic with spacefaring adventure. This dynamic setting has come to fifth edition, giving players the opportunity to set a course for Wildspace and distant stars. What does this mean for Eberron? What’s the best way to take your campaign to the skies and beyond?

Eberron: Rising From The Last War states that “Eberron is part of the Great Wheel of the multiverse… At the same time, it is fundamentally apart from the rest of the Great Wheel, sealed off from the other planes even while it’s encircled by its own wheeling cosmology. Eberron’s unique station in the multiverse is an important aspect of the world… it is sheltered from the influences and machinations of gods and other powers elsewhere in the Great Wheel.” Now, Rising also says that if you WANT to integrate Eberron with other settings you can; as a DM, you can say that whatever protections have hidden Eberron from the worlds beyond are failing. So there’s nothing stopping you from making a campaign where there’s regular commerce or even war between Realmspace and Eberron’s wildspace system—let’s call it Siberspace. But personally, I’m more interesting in combining the two concepts in a very different way—in finding an approach that adds depth to the moons, the Ring, and the existing cosmology of Eberron rather than leaving it behind.

One of the core principles of Eberron is that arcane magic is a form of science and that it evolves—that invention and innovation should play a role in the setting. With this in mind, in bringing Spelljammer into Eberron I’d emphasize that this isn’t a retcon, it’s a new development. The Five Nations have never had spelljammers until now. The adventurers aren’t the latest recruits in a vast, well-established spelljamming fleet; they are among the very first humanoids to venture into wildspace to try reach the moons of Eberron.

With this in mind, an important question is why no one’s gone into space. The Ring of Siberys is beyond the atmosphere, but what’s stopping me from putting on a ring of sustenance and pointing my broom of flying straight up? In my campaign, there are three major obstacles. The first is that the Ring and the moons are beyond Eberron’s atmosphere, so you need to be able to survive in wildspace. The second is that breaking free from Eberron’s gravity is a challenge, requiring a surge of energy a simple item like a broom of flying can’t produce. The third is that the Ring of Siberys radiates arcane energy. As discussed below, this specifically interferes with divination and teleportation, but it can overload any arcane system… and this seems to especially impact magic of flight. It’s almost like the Progenitors didn’t want people to leave the planet. But why take the hint? These are problems that can be overcome, and now they have; the people of Eberron have developed spelljammers that can reach the Ring and beyond. Still, the key is that this is all happening now, in 998 YK. And different nations are using very different techniques to overcome these obstacles—each of which could have unexpected problems.

In developing a Spelljammer campaign based on the space race, a key question is who’s in the race? My preference is to focus on the Five Nations. No one won the Last War, and fear of the Mourning prevents anyone from restarting it; there’s still tension, resentment, and intrigue. So in addition to the excitement of going where no one has gone before, I’d emphasize the tension between nations and the impact triumphs in space could have back home. Just as in our world, the space race could become a proxy for this conflict, driven by national pride and the determination not to let another nation secure a tactical advantage in space. The Treaty of Thronehold still holds, and it would take intense provocation to cause an Aundairian ship to open fire on a Brelish ship—but the nations are bitterly competitive and will do anything short of war to get an edge over their rivals. Finding awesome space treasure is great, but forming alliances and establishing outposts could be the most important elements of an adventure.

So with this in my mind, I’d focus on three primary forces. The Dragonmarked Houses are willing to work with every nation, but this is also a chance to explore the growing division within House Cannith, suggesting that each of the three barons are backing a different nation and that the rivalry between these three is almost as strong as the cold war between the nations.

Aundair dares, and that motto certainly applies to its spelljamming program. Rather than pursuing the established path of elemental binding, this branch of the Arcane Congress is blending cutting edge arcane science with Thelanian wonder. The Brelish say that Aundair traded an old cow for a spelljamming engine, and while that’s a mocking exaggeration, it’s not entirely untrue; the ir’Dalan line has a long association with the archfey known as the Mother of Invention, and the Archmagister Asta ir’Dalan has brought wizards and warlocks together in a unique alliance. The current Aundairian ships are the fastest and most maneuverable of the three main powers, and unquestionably the most beautiful. A few key notes about the Dragonhawk Initiative…

As research vessels, the crew of a Dragonhawk ship focuses more on arcane sophistication and on skill than brute force. Every ship will have at least one wizard and one warlock. An eldritch knight could be appointed as security chief, but a battlemaster or barbarian would be an unlikely addition to the crew. Baron Jorlanna d’Cannith isn’t as closely involved with the Dragonhawk Initiative as her rival barons are with their nations, but Cannith West is manufacturing elements of the Aundairian spelljammers and could become more actively involved in the future.

The Argosy is a branch of the King’s Citadel, formed in close alliance with Zilargo, Cannith South under Merrix d’Cannith, and House Lyrandar. Where the Dragonhawk Initiative is scientific and the Blade of Siberys is a branch of the military, the King’s Argosy is ultimately a commercial enterprise; its mission is to seek profit in the heavens, to secure unique resources and opportunities that can benefit Breland and its sponsors. Argosy ships rely on the established principles of the elemental binding; they are essentially bulkier, overpowered elemental airships, including the need for a Lyrandar pilot. Compared to the Dragonhawks, Argosy ships are ugly; but they are sturdy, and thanks to Breland’s industrial capacity the Argosy has the largest fleet of the Five Nations. A few core principles of the King’s Argosy…

Argosy crews place a strong emphasis on skill expertise and versatility; there’s always a few jacks of all trades ready to step into the shoes of a fallen specialist. Brelish ships always have at least one warforged or autognome; a Lyrandar pilot; and an artificer, who could be Brelish, Cannith, or Zil. It’s worth noting that while the King’s Argosy is works closely with the Twelve, the two are still ultimately independent. By allowing an Optech on board, the Argosy maximizes the chances of forging profitable arrangements. But the Optech is an adviser who has no actual authority on the ship. And should Aundair or Karrnath come into possession of a valuable resource, the Twelve would negotiate with them. Breland is making business and industry the focus of its mission in space, and thus has encouraged a strong role for the Twelve, but it’s not an exclusive arrangement.

Where the King’s Argosy hopes to profit from the stars, the Blade of Siberys seeks only one thing: victory. An alliance between the Karrnathi crown and Cannith East (under Zorlan d’Cannith), the Blade is certain that there will eventually be a war in the stars—and when that comes to pass, Karrnath will hold the winning hand. Vital resources? Strategic positions? Alien weapons or allies? The Blade wants them all. A few details about the Blade of Siberys…

Every Blade vessel has a necromancer-engineer, and could have an oathbreaker paladin in charge of marines. While there are Karrn necromancers who aren’t part of the Blood of Vol, this could be a case where Seekers are given positions—a major opportunity to repair the relationship between the crown and the Blood of Vol. In general, the Karrns are more concerned with martial force than diplomacy, and strength over finesse. It’s important to keep in mind that the conflict between the Five Nations is still a cold war; with their heavy armament the Blade is prepared for that to change, but as things stand an attack on one of the other nations would be a political catastrophe. But the next war could start tomorrow, and even if it doesn’t, you never know what enemies might be waiting among the moons.

In this campaign, Aundair, Karrnath, and Breland are the three major powers in the space race; it takes the resources of a nation to get off the ground. However, over the course of the campaign other groups could make their way into space. Most of these would be operating on a smaller scale, with one or two ships rather than building up a fleet, but they could still pose unexpected challenges or become useful allies over time.

The Treaty of Thronehold specifically forbids the creation of warforged and the use of the creation forges, but it places no further restrictions on the creation of sentient construct. Over the last two years, Merrix d’Cannith has been working closely with the brilliant binder Dalia Hal Holinda to develop a new form of construct fused by an elemental heart. Over the last year this work has born fruit, but so far the bound heart can only sustain a small form; this is the origin of the autognome.

As of 998 YK, there are approximately 43 autognomes in existence. Each autognome is a hand-crafted prototype, and every one of them is unique; Merrix and Dalia are still experimenting, changing materials, designs, and technique. One autognome might have arcane sigils carved on every inch of its bronze skin. Another might be made with chunks of Riedran crysteel, which glow when the autognome is excited. What all autognome designs share is an elemental heart—a Khyber shard core inlaid with silver and infused with the essence of a minor elemental. This serves both as the heart and brain of an autognome, keeping it alive and also serving as the seat of its sentience. The minor elementals involved in this process aren’t sentient as humans understand the concept; but through the process of the binding, it evolves into something entirely new.

In creating an autognome character, begin by deciding the nature of your elemental heart. You may not remember your existence as a minor elemental, but the nature of your spark may be reflected by your personality. Are you fiery in spirit? A little airheaded? Do you have a heart of stone? What was the purpose you were made for, and how is this reflected in your design? Which of your class abilities are reflected by your physical design, and which are entirely learned skills? And most of all, what drives you? Are you devoted to your work, or are you driven by insatiable curiosity or a desire to more deeply explore your own identity?

Autognomes aren’t widely recognized and may be mistaken for warforged scouts. If their existence becomes more widely known, will anyone will seek to amend the Code of Galifar to protect all constructs? Will the Lord of Blades see autognomes as allies in the struggle, or deny any kinship to these elemental constructs?

While I’m suggesting the Cannith autognome as the most common form of autognome, it’s not the only way to use this species. In my current campaign I’ve proposed an Autognome warlock as a crewmember on a Dragonhawk ship—a construct built with the ship, who serves as its Arbiter. But here again, this character is a unique construct who doesn’t resemble Cannith’s creations or feel any immediate kinship with them.

In simplest terms, Khyber is the underworld, Eberron the surface, and Siberys the sky; as such, the crystal sphere containing Eberron and its moons is typically referred to as Siberspace. Korranberg scholars maintain that Berspace would be a more accurate term; “Ber” is thought to be an ancient word meaning “dragon” or “progenitor,” and as such Berspace could be seen as The Realm of the Progenitors. However, beyond Korranberg the idea was dismissed because people felt ridiculous saying “Brrr, space.”

So what awaits in the Realm Above? Compared to the endless expanse of the Multiverse, it may seem relatively limited, but there’s many opportunities for adventure.

The first step into the sky is the Ring of Siberys, the glittering belt of golden stones that’s wrapped around Eberron. The Ring has long been an enigma. It is a powerful source of arcane energy, and this ambient radiation—commonly referred to as the blood of Siberys—has a number of effects.

The Blood of Siberys is an obstacle, but it can be overcome. Elemental airships couldn’t reach the Ring, so the Five Nations developed spelljammers. The Mysterious and Anchoring effects can surely also be overcome with research and development; this is an opportunity to reflect the evolution of arcane science. Most likely this would come in stages rather than all at once; the Dragonhawk Initiative learns to cast detect magic through the Mysterious interference, then any 1st level divination, then any 2nd level, and so on. The breakthrough could involve a rare resource, such as a previously unknown mineral only found in the Ring; deposits of this mineral would quickly become be important strategic objectives. Can House Orien create a focus item that allows them to teleport to the Ring? Who will penetrate the shrouding effect first—Aundair or House Medani?

So to this point, the people of Khorvaire haven’t been able to use divination to study the Ring, and they haven’t had ships that could reach it. What will the first spelljammers find? Legend has long held that the Ring of Siberys is comprised entirely of Siberys dragonshards; the King’s Argosy will be disappointed to learn that this is only a myth. There are Siberys shards spread throughout the Ring of Siberys, but the bulk of the ring is comprised of massive chunks of stone and ice surrounded by fields of smaller shards. The Ring is airless and cold—or so it first appears. The blood of Siberys doesn’t just shield the Ring; it makes the impossible possible. Some of the larger stone shards have some combination of gravity, breathable air, safe temperatures, or even fertile soil (though based on other conditions, it might be impossible to grow typical crops of the world below). Usually these features are only found on the interior of a sky island; it’s barren and airless on the surface, but if you find a passage there’s a hidden oasis within. Such an oasis will be an incredible discovery for exploring spelljammers, but there’s a complication: the Five Nations aren’t the first civilizations to explore the Ring. Some of the larger shards—shards the size of Lhazaar islands—contain ruins of civilizations that died long ago. Some hold stasis fields or extradimensional spaces, waiting for an explorer to deactivate the wards or unlock the space. These can contain powerful artifacts or priceless arcane secrets… or they could contain magebred beasts, ancient plagues, or even entire outposts held in stasis. Consider a few possible origins for such things…

Personally, I’d be inclined to say that native fiends have a minimal presence in the Ring of Siberys. The overlords are part of the architecture of Khyber. They might be able to influence people in the Ring, as with the Daughter of Khyber corrupting dragons; but there are no overlords bound in the ring itself.

Overall, the Ring of Siberys is the first frontier. It is vast—it stretches around the entire world, and has room for countless shards the size of cities or even islands. Mineral deposits and stasis caches are tempting treasures, and a habitable oasis would be an invaluable foothold in space. However, the block against divination limits the ability to swiftly locate these things… and that’s where adventurers come in.

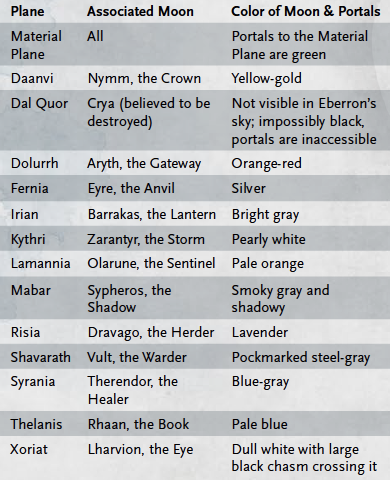

The people of the Five Nations have never reached the moons of Eberron, and there are many theories about them. Some assert that the moons must be airless, arid chunks of rock. Others say that the moons aren’t actually physical objects, but rather massive planar gateways—that a ship that tries to land on Vult will actually find itself in Shavarath. In my campaign, the answer lies between these two options. The moons are essentially manifest worlds. Each moon is closely tied to a particular plane, and the entire moon has traits that are typically associated with manifest zones of that plane. All of Sypheros is blanketed in Eternal Shadows of Mabar, while Barrakas has the Pure Light trait of Irian. The moons have atmosphere and gravity. Vegetation varies—Sypheros and icy Dravago are quite barren, while Barrakas and Olarune and lush and overgrown. While each moon is suffused with planar energies, these are concentrated in specific spaces. All of Eyre has the Deadly Heat trait of Fernia, but there are only a few places regions with the Fires of Industry trait—and those spaces would be quite desirable as outposts. However, it’s quite possible that these valuable locations have already been claimed. The moons support life, and it’s up to the DM to decide exactly what’s already there. I don’t want to go into too much detail, because this is where the exploration comes in. Here’s a few general options…

Savage and Untamed. There’s no civilization on this moon, but there is life—powerful and dangerous life. Any nation that hopes to establish an outpost or to explore extensively will have to deal with any combination of deadly monsters, supernatural hazards, dramatic weather effects, and more. It’s quite possible that one or more of these effects are so dangerous that it’s essentially impossible to maintain an outpost or establish a colony on the moon. If Zarantyr has the Constant Change or Chaotic Time traits of Kythri it could be very dangerous to remain there for long, while Olarune could be like the Titan’s Folly layer of Lamannia—any attempt to impose order upon the natural world will be overcome.

Lunar Empires. A moon could be home to one or more powerful civilizations. Perhaps the Giff have an imperial civilization on Vult, with fortresses spread across the moon. The moons are smaller than Eberron, so even a powerful lunar civilization will be limited in scope; but this is still an important opportunity for first contact and ongoing diplomacy. These societies could have technology or magic unknown on Khorvaire. If the Giff are on Vult, they could have their faithful firearms! A crucial question is whether these lunar civilizations have spelljammers of their own, or if they are landbound. The fact that none of these nations have made contact with Eberron suggests that they don’t have space travel, but it’s always possible that they have limited spelljammers that can cross between moons but can’t get past the Ring. This would allow the Giff of Vult to be engaged in a bitter war against the Plasmoids of Zarantyr and for the spelljammers of Eberron to get caught up in this conflict and to engage in battles in space, but this conflict can’t reach Eberron… at least for now!

Small Civilizations. A moon could have one or more civilizations that could interact with explorers, but that aren’t so vast and advanced as to truly dominate their moon. Perhaps there’s a few clans of Hadozee on Olarune—each carrying a different form of lycanthropy! Each claims a region within Olarune, and explorers will need to negotiate with multiple clans… being careful to learn and respective their dramatically different cultures! This sort of division could also lead to the different nations finding different allies on the same moon. On Olarune, the Blade of Karrnath could forge a bond with the powerful Wolf clan, while the King’s Argosy negotiates with the Tigers and Bears.

Planar Extensions. Personally, I want the moons to be unique worlds that are influenced by their associated planes, but that are distinctly different from what you’d find in those planes. I’d rather have Vult have a Gith empire than to just make it another front in the war between the celestials and fiends of Shavarath. However, a moon could certainly have a region that is either a direct extension of a plane or that hosts the denizens of the plane. It could be that the Feyspires of Thelanis appear on Rhaan as well as on Eberron, and that explorers could find Pylas Pyrial waiting for them when they land. Or people could land on Aryth to discover a city inhabited by the ghost of their lost loved ones… but is it real, or some sort of deadly trick?

I don’t want to know all the answers; that’s why we have a journey of discovery. But there’s at least twelve moons to explore, and each one can present very different challenges and hold different rewards. Will the adventurers be drawn into intralunar wars? Will they engage in high stakes first contact with alien civilizations? Or will the greatest challenge be surviving an expedition?

Wroat, We Have A Problem…

The moons and the Ring are the main real estate, but the space race isn’t just about the destination—it’s all about the journey, and the many, many things that could go wrong in space. In my campaign, I’d want to emphasize that space travel is new. Every ship is a protoype, and the people of Khorvaire simply don’t know what threats are waiting for them in space. In addition to the hazards presented in Spelljammer content, adventurers could run across manifest zones, wild zones, or supernatural threats never encountered planetside. A Shavaran bloodstorm could induce homicidal aggression in humanoids that pass through it, while a Lamannian sargasso could bury its roots in any ship that draws too close. There’s a giant Khyber crystal floating in space… is it a valuable resource or does it contain an incredibly dangerous spirit? And just in general, what do the adventurers do when something goes wrong with their ship? And do they think it’s just a legitimate malfunction—a lesson artificers can learn from—or is it sabotage? Is there a spy among their crew… or has an alien threat come on board?

As depicted in Spelljammer: Adventures in Space, Wildspace bleeds naturally into the Astral Sea; all you need to do is sail far enough. However, as called out in Rising From The Last War, Siberspace is isolated from the rest of the Multiverse. Exploring Eberron suggests that Eberron is the only planet in its material plane—that the stars are in fact glittering points on a crystal sphere, surrounded by the vast astral void. In my Space Race campaign, the first Spelljammers won’t be capable of reaching any form of the Astral; they’ll have to discover the limits of Siberspace and find out how to pass beyond it. This could be driven by encounters with Githyanki raiders, or require the adventurers’ patrons to bargain with Aerenal. But even when they pierce this veil, I wouldn’t take them to the full expanse of the Astral Sea. This article presents a version of the Astral Plane holding countless ruins, timelost hermitages, and outposts like Pylas Tar-Volai and Tu’narath. But it’s still an interpretation concretely tied to Eberron, home to the Githyanki survivors of a lost reality and the experiments of the Undying Court. Personally, I’d say that this version of the Astral Plane is still part of Siberspace—that just as there’s a barrier around Eberron’s material plane, its astral plane is also a shielded pocket within the greater Astral Sea.

Another point is that Siberspace can be larger that people thought. Exploring Eberron says that Eberron is the only true planet in its system. But if the twelve moons and the Astral plane aren’t enough for your adventures, there could always be one or more planets in the system that astrologers have somehow overlooked. Perhaps the Illithids of Thoon live on the dark side of a world that’s been completely blacked out, invisible and deadly.

Where are the Giff in Eberron? Where could we find a megapede? In general, this is where exploration comes into play. Who knows what the adventurers will find on the moons? In my campaign, at least a few of the moons will have significant civilizations, who may well have intralunar travel and simply never have crossed the Ring of Siberys to reach Eberron. I’ve suggested the idea of the Giff as an imperialistic society on Vult—with the moon’s ties to Shavarath fueling their warlike nature—or the plasmoids being found on Zarantyr, with their fluid forms reflecting the chaos of Kythri—but those are just possibilities. There could be a single city of Mercanes on Therendor, with a gate connected to the Immeasurable Market of Syrania; they carry the goods of the Market to other moons. Neogi could have a civilization on Lharvion, or they could actually be the remnants of some long-forgotten civilization on Eberron itself, and dwell in outposts hidden in the Ring of Siberys. Space Hamsters could be found on Olarune, with other Lammania-influenced megafauna. A few other random ideas…

Again, all of these are just possibilities; if you want space hamsters to have a mighty empire on Therendor, follow that story! Meanwhile, if you want to play a giff, hadozee, or any of the other new species, that’s what the Astral Drifter and Wildspacer backgrounds are for. I especially like Astral Drifter; your character was marooned in the Astral and lost for countless decades. You finally escaped into Eberron, where your stories of space may have inspired the current drive to reach space. But because you’ve been gone for so long, you don’t know what you’ll find when you return to your home moon. If could be that your Giff character remembers your great empire on Vult, but that since you’ve been gone it’s been entirely obliterated by illithids and neogi!

One last thing: people may say Do Giff have guns in Eberron? Why wouldn’t they? I’ve never had any issue with the existence of firearms; in a previous article I’ve suggested that the Dhakaani could use them on Eberron. I just prefer to focus the Five Nations on wandslingers and other arcane alternatives. With that said, I might still think about ways to make Giff firearms feel unique to the setting. If the Giff are based on Vult, perhaps their firearms use the powdered remnants of angels instead of gunpowder; the ashes of the eternal wars of Shavarath drift across the surface of the moon.

As I’ve said above, part of what I love about the Space Race campaign is the idea that it’s happening right now and that the action in space should have real consequences on the planet below. With this in mind, I’d personally play with the passage of time in a different way than in most of my campaigns.

Another way to approach this would be to have each player make two characters—a member of the spelljammer crew and someone who’s involved in the diplomacy, administration, or research efforts on the ground. These planetbound characters might not be as combat-capable as the explorers, but they each have vital resources and influence; they’ll never actually get into a battle on a grid map, but they’ll be making the crucial decisions that determine the greater arc of the campaign. These could be people who are important but not the top decision makers, or they could actually be the central players; if you’re running an Argosy campaign, one of the players could be King Boranel, another Merrix d’Cannith, another the head of the Zil binders. Again, these characters wouldn’t actually have full stats and character sheets, but the players would have to play them in negotiations and decide what they commit to during downtime—does Merrix support the colony or does he devote his resources to building a better autognome?

As I said, this is the campaign I want to run. But Spelljammer is designed to allow adventures across the multiverse, and if that’s the story you want to tell, tell it! There’s nothing wrong with having your spelljammers crash land on Krynn. If you want to retrofit the two together, you could say that Galifar had a long-established spelljamming fleet with outposts in the Ring of Siberys; during the Last War, the Ring seceded and now exists as its own independent force that protects Siberspace from outside threats and continues to explore the multiverse. There are some cosmological questions you’ll have to resolve, but again, if that’s the story you want to tell, there’s always answers!

I’m juggling many things, and I won’t be answering questions on this article. But if you’d like to see more of how I’d run such a campaign, you can—and you can even play in it! For the rest of the year, I’m shifting my Threshold Patreon to running a Siberspace campaign. Every month I run and record a session. The characters and the story are persistent, but the players change each session; every Threshold patron has a chance to get a seat at the table. Even if you never get a seat at the table, you have access to the recorded sessions and you have an opportunity to shape the story through polls, Discord discussions, and story hours. Currently I’m going through the Session Zero with the patrons; we’ve decided to base the campaign on the Dragonhawk Initiative, and we’re developing the player characters. If you’d like to be a part of it, become a patron!

Thanks as always to my patrons for making these articles possible, and good luck to all of you in your adventures in space!

House Tharashk is the youngest Dragonmarked house. The Mark of Finding first appeared a thousand years ago, and over the course of centuries the dragonmarked formed three powerful clans. It was these clans that worked with House Sivis, joining together in the model of the eastern houses. The name of the House—Tharashk—is an old Orc word that means united. Despite this, heirs of the house typically use their clan name rather than the house name. They may be united, but in daily life they remain ‘Aashta and Velderan.

The Dragonmarks are driven by more than simple genetics. In most dragonmarked houses, about half of the children develop some level of dragonmark. Over the course of a thousand years of excoriates and voluntary departures, many people in Khorvaire have some trace of dragonmarked blood. And yet, foundlings—people who develop a dragonmark outside a house—are so rare that many foundlings are surprised to learn that they have a connection to a house. Many houses allow outsiders to marry into their great lines, and the number of dragonmarked heirs born to such couples within the houses is dramatically higher than those born to excoriates outside of the houses. Scholars have proposed many theories to explain this discrepancy. Some say that it’s tied to proximity—that being around large numbers of dragonmarked people helps to nuture the latent mark within a child. Others say that it’s related to the tools and equipment used by the houses, that just being around a creation forge helps promote the development of the Mark of Making. One of the most interesting theories comes from the sage Ohnal Caldyn. A celebrated student of the Draconic Prophecy, Caldyn argued that the oft-invoked connection between dragonmarks and the Prophecy might be misunderstood—that rather than each dragonmarked individual having significance, the Prophecy might be more interested in dragonmarked families. It’s been over two thousand years since the Mark of Making appeared on the Vown and Juran lines of Cyre—and yet those families remain pillars of the house today.

This helps to explain the core structure of Tharashk, sometimes described as one, three, and many. There are many minor families within House Tharashk, but each of these is tied to one of the three great clans: Velderan, Torrn, and ‘Aashta. The house is based on the alliance between these three clans, and where most dragonmarked houses have a single matriarch or patriarch, Tharashk is governed by the Triumvirate, a body comprised of a leader from each of these clans.

When creating an adventurer or NPC from House Tharashk, you should decide which of the great clans they’re tied to. Each clan is tied to lesser families, so you’re not required to use one of these three names. A few lesser families are described here along with each clan, but you can make up lesser families. So you can be Jalo’uurga of House Tharashk; the question is which clan the ‘Uurga Tharashk are connected to. In theory, the loyalty of a Tharashk heir should be to house first, clan second, and family third. Heirs are expected to set aside family feuds and to focus on the greater picture, to pursue the rivalry between Deneith and Tharashk instead of sabotaging house efforts because of an old feud between ‘Uurga and Tulkar. But those feuds are never forgotten—and when it doesn’t threaten the interests of house or clan, heirs may be driven by these ancient rivalries.

To d’ or not to d’? Tharashk has never been bound by the traditions of the other houses, and this can be clearly seen in Tharashk names. Just look to the three Triumvirs of the house. All three possess dragonmarks, yet in the three of them we see three different conventions. Khandar’aashta doesn’t bother with the d’ prefix or use the house name. Daric d’Velderan uses his clan name, but appends the d’ as a nod to his dragonmark. Maagrim Torrn d’Tharashk uses the d’ but applies it to the house name; no one uses d’Torrn. Maagrim’s use of the house name makes a statement about her devotion to the alliance and the house. Daric’s use of the ‘d is a nod to the customs of the other houses. While Khandar makes no concessions to easterners. He may the one of the three leaders of House Tharashk, but he is Aashta. As an heir of House Tharashk, you could follow any of these styles, and you could change it over the course of your career as your attitude changes.

Orcs, Half-Orcs, and Humans. By canon, the Mark of Finding is the only dragonmark that appears on two ancestries—human and half-orc. However, by the current rules, the benefits of the Mark replace everything except age, size, and speed. Since humans and half-orcs have the same size and speed, functionally it makes very little difference which you are. It’s always been strange that this one mark bridges two species when the Khoravar marks don’t, and when orcs can’t develop it. As a result, in my campaign I say that any character with the Mark of Finding has orc blood in their veins. The choice of “human” or “half-orc” reflects how far removed you are from your orc ancestors and how obvious it is to people. But looking to the Triumvirs above, they’re ALL Jhorgun’taal; it’s simply that it’s less obvious with Daric d’Velderan. In my campaign I’d say that Daric has yellow irises, a slight point to his ears, and notable canine teeth; at a glance most would consider him to be human, but his dragonmark is proof that he’s Jhorgun’taal.

Characters and Lesser Clans. The entries that follow include suggestions for player characters from each clan and mention a few lesser clans associated with the major ones. These are only suggestions. If you want to play an evil orc barbarian from Clan Velderan, go ahead—and the lesser clans mentioned here are just a few examples.

The Azhani Language. Until relatively recently, the Marches were isolated from the rest of Khorvaire. The Goblin language took root during the Age of Monsters, but with the arrival of human refugees and the subsequent evolution of the blended culture, a new language evolved. Azhani is a blending of Goblin, Riedran, and a little of the long-dead Orc language. It’s close enough to Goblin that someone who speaks Goblin can understand Azhani, and vice-versa; however, nuances will be lost. For purposes of gameplay, one can list the language as Goblin (Azhani). More information about the Azhani language can be found in Don Bassinthwaite’s Dragon Below novels.

Before the rise of House Tharashk, most of the clans and tribes of the Shadow Marches lived in isolation, interacting only with their immediate neighbors. Velderan has always been the exception. The Velderan have long been renowned as fisherfolk and boatmen, driving barges and punts along the Glum River and the lesser waters of the Marches and trading with all of the clans. The clan is based in the coastal town of Urthhold, and for centuries they were the only clan that had any contact with the outside world. It was through this rare contact that reports of an unknown dragonmark made their way to House Sivis, and it was Velderan guides who took Sivis explorers into the Marches.

That spirit remains alive today. Where ‘Aashta and Torrn hold tightly to ancient—and fundamentally opposed—traditions, it’s the Velderan who dream of the future and embrace change, and their enthusiasm and charisma that often sways the others. Torrn and ‘Aashta are both devoted to the work of the house and the prosperity of their union, but it’s the Velderan who truly love meeting new people and spreading to new locations, and who are always searching for new tools and techniques. Stern ‘Aashta are always prepared to negotiate from a position of strength, but it’s the more flexible Velderan who most often serve as the diplomats of the house. While they work with House Lyrandar for long distance trade and transport, the Velderan also remain the primary river runners and guides within the Marches.

In the wider world, the Velderan are often encountered running enclaves in places where finesse and diplomacy are important. Beyond this, the Velderan are most devoted to the inquisitive services of the house; Velderan typically prefer unraveling mysteries to the more brutal work of bounty hunting. The Velderan have no strong ties to either the Gatekeepers or the “Old Ways” of Clan ‘Aashta; they are most interested in exploring new things, and are the most likely to adopt new faiths or traditions. Many outsiders conclude that the Velderan are largely human, and they do have a relatively small number of full orcs as compared to the other clans, but Jhorguun’taal are in the majority in Velderan; it’s just that most Velderan Jhorgun’taal are more human in appearance than the stereotype of the half-orc that’s common in the Five Nations.

Overall, the Velderan are the glue that holds Tharashk together. They’ve earned their reputation for optimism and idealism, and this is reflected by their Triumvir. However, there is a cabal of elders within the house—The Veldokaa—who are determined to maintain the union of Tharashk but to ensure that Velderan remains first among equals. Even while Velderan mediates between Torrn and ‘Aashta, the Veldokaa makes sure to keep their tensions alive so that they rarely ally against Velderan interests. Likewise, while it’s ‘Aashta who is most obvious in its ambition and aggression, it’s the Veldokaa who engage in more subtle sabotage of rivals. So Velderan wears a friendly face, and Daric d’Velderan is sincere in his altruism. But he’s not privy to all the plans of the Veldokaa, and there are other clan leaders—such as Khalar Velderan, who oversees Tharashk operations in Q’barra—who put ambition ahead of altruism.

Velderan Characters. With no strong ties to the Gatekeepers or the Dragon Below, Velderan adventurers are most often rangers, rogues, or even bards. Velderan are interested in the potential of arcane science, and can produce wizards or artificers. Overall, the Velderan are the most optimistic and altruistic of the Clans and the most likely to have good alignments—but an adventurer with ties to the Veldokaa could be tasked with secret work on behalf of the clan. Velderan most often speak Common, and are equally likely to speak Azhani Goblin or traditional Goblin.

Triumvir. Clan Velderan is currently represented by Daric d’Velderan. Daric embodies the altruistic spirit of his clan, and hopes to see Tharashk become a positive force in the world. His disarming humor and flexibility play a critical role in balancing the stronger tempers of Maagrim and Khandar. Daric wants to see the house expand, and is always searching for new opportunities and paths it can follow, but he isn’t as ruthless as Khandar’aashta and dislikes the growing tension between Tharashk and House Deneith. Daric is aware of the Veldokaa and knows that they support him as triumvir because his gentle nature hides their subtle agenda; he focuses on doing as much good as he can in the light while trusting his family to do what they must in the shadows.

Lesser Clans. The Orgaal are an orc-majority clan, and given this people often forget they’re allied with Velderan; as such, the Veldokaa often use them as spies and observers. The Torshaa are expert boatmen and are considered the most reliable guides in the Shadow Marches. The Vaalda are the finest hunters among the Velderan; it’s whispered that some among them train to hunt two-legged prey, and they produce Assassin rogues as well as hunters.

Torrn is the oldest of the Tharashk clans. The city of Valshar’ak has endured since days of Dhakaan, and holds a stone platform known as Vvaraak’s Throne. While true, fully initiated Gatekeepers are rare even within the Marches, the Torrn have long held to the broad traditions of the sect, opposing the Old Ways of ‘Aashta and its allies. Clan Torrn has the strongest traditions of primal magic within the Reaches, and ever since the union Torrn gleaners can be found providing vital services across the Marches; it was Torrn druids who raised the mighty murk oaks that serve as the primary supports of Zarash’ak. However, the clan isn’t mired in the past. The Torrn value tradition and are slow to change, but over the last five centuries they have studied the arcane science of the east and blended it with their primal traditions; there are magewrights among the Torrn as well as gleaners.

The Torrn are known for their stoicism and stability; a calm person could be described as being as patient as a Torrn. They refuse to act in haste, carefully studying all options and relying on wisdom rather than being driven by impulse or ambition. Of the three clans, they have the greatest respect for the natural world, but they also know how to make the most efficient use of its bounty. While ‘Aashta have always been known as the best hunters and Velderan loves the water, Torrn is closest to the earth. They are the finest prospectors of the Marches, and are usually found in charge of any major Tharashk mining operations, blending arcane science and dragonmarked tools with the primal magic of their ancestors. Most seek to minimize long-term damage to the environment, but there are Torrn overseers—especially those born outside the Marches—who are focused first and foremost on results, placing less weight on their druidic roots and embracing the economic ambitions of the house.

Most Torrn follow the basic principles of the Gatekeepers, which are not unlike the traditions of the Silver Flame—stand together, oppose supernatural evil, don’t traffic with aberrations. However, most apply these ideas to their own clan and to a wider degree, the united house. Torrn look out for Tharashk, but most aren’t concerned with protecting the world or fighting the daelkyr. Torrn miners may use sustainable methods in their mining, but they are driven by the desire for profit and to see their house prosper. However, there is a deep core of devoted Gatekeepers at the heart of Torrn. Known as the Valshar’ak Seal, they also seek to help Tharashk flourish as a house—because they wish to use its resources and every-increasing influence in the pursuit of their ancient mission. Again, most Torrn follow the broad traditions of the Gatekeepers, but only a devoted few know of the Valshar’ak Seal and its greater goals.

Within the world, the Torrn are most often associated with mining and prospecting, as well as construction and maintaining the general infrastructure of the house. The Torrn Jhorguun’taal typically resemble their orc ancestors, and it’s generally seen as the Clan with the greatest number of orcs.

Torrn Characters. Whether or not they’re tied to the Gatekeepers, Torrn has deep primal roots. Tharashk druids are almost always from Torrn, and Tharashk rangers have a strong primal focus; a Torrn Gatekeeper could also be an Oath of the Ancients paladin, with primal trappings instead of divine. The Torrn are stoic and hold to tradition, and tend toward neutral alignments. Most speak Azhani Goblin among themselves, though they learn Common as the language of trade.

Triumvir. Maagrim Torrn d’Tharashk represents the Torrn in the Triumvirate. The oldest Triumvir, she’s known for her wisdom and her patience, though she’s not afraid to shout down Khandar’aashta when he goes too far. Maagrim supports the Valshar’ak Seal, but as a Triumvir her primary focus is on the business and the success of the house; she helps channel resources to the Seal, but on a day to day basis she is most concerned with monitoring mining operations and maintaining infrastructure. She is firmly neutral, driven neither by cruelty or compassion; Maagrim does what must be done.

Lesser Clans. The Torruk are a small, orc-majority clan with strong ties to the Gatekeepers, known for fiercely hunting aberrations in the Reaches and for clashing with the ‘Aashta. The Brokaa are among the finest miners in the house and are increasingly more concerned with profits than with ancient traditions.

The ‘Aashta have long been known as the fiercest clan of the Shadow Marches. Their ancestral home, Patrahk’n, is on the eastern edge of the Shadow Marches and throughout history they’ve fought with worg packs from the Watching Wood, ogres and trolls, and even their own Gaa’aram cousins. Despite the bloody history, the ‘Aashta earned the respect of their neighbors, and over the last few centuries the ‘Aashta began to work with the people of what is now Droaam. The ‘Aashta thrive on conflict and the thrill of battle; they have always been the most enthusiastic bounty hunters, and during the Last War it was the ‘Aashta who devised the idea of the Dragonne’s Roar—brokering the service of monstrous mercenaries in the Five Nations, as well as the services of the ‘Aashta themselves.

The ‘Aashta are devoted to what they call the “Old Ways”—what scholars might identify as Cults of the Dragon Below. The two primary traditions within the ‘Aashta are the Inner Sun and the Whisperers, both of which are described in Exploring Eberron. Those who follow the Inner Sun seek to buy passage to a promised paradise with the blood of worthy enemies. The Whisperers are tied to the daelkyr Kyrzin; they’re best known for cultivating gibbering mouthers, but they have other traditions tied to the Bile Lord. The key point is that while the ‘Aashta are often technically cultists of the Dragon Below, they aren’t typically trying to free a daelkyr or an overlord. The ‘Aashta Inner Sun cultist is on a quest to find worthy enemies, to buy their own passage to paradise; they aren’t looking to collapse the world into chaos or anything like that. The Gatekeepers despise the cults for trafficking with malefic forces, and believe that they may be unwitting tools of evil, and it’s these beliefs that usually spark clashes between the two (combined with the fact that Gatekeeper champions are certainly ‘worthy foes’ in the eyes of the Inner Sun). But it’s important to recognize that these two paths have co-existed for thousands of years. That co-existence hasn’t always been peaceful, but they’ve never engaged in a total war. Since the union of Tharashk, both ‘Aashta and Torrn have done their best to work together, with Velderan helping to mediate between the two (… and with the Veldokaa occasionally stirring up the conflict).

The ‘Aashta are fierce and aggressive. They respect strength and courage, and take joy in competition. Having invested in the Tharashk union, they want to see the House rise to glory. It’s the ‘Aashta who pushed to create the Dragonne’s Roar despite the clear conflict with House Deneith. The ‘Aashta also recognize the power Tharashk has as the primary supplier of dragonshards, and wish to see how the house can use this influence. In contrast to the Veldokaa, the ‘Aashta are honest in their ambition and wish to see the house triumph as a whole. While they do produce a few inquisitives, their greatest love is bounty hunting, and most Tharashk hunters come from ‘Aashta or one of its allied clans.

While they aren’t as dedicated to innovation as Velderan and aren’t as invested in symbionts as the dwarf clans of Narathun or Soldorak in the Mror Holds, the ‘Aashta are always searching for new weapons and don’t care if a tool frightens others. Some of those who follow the Old Ways master the techniques of the warlock, while the Whisperers employ strange molds and symbionts tied to Kyrzin and produce gifted alchemists.

‘Aashta Characters. The ‘Aashta are extremely aggressive. While there are disciplined fighters among them—often working with the Dragonne’s Roar to train and lead mercenary troops—the ‘Aashta are also known for cunning rangers and fierce barbarians. Their devotion to the Old Ways can produce warlocks or sorcerers, and especially gifted Whisperers can become Alchemist artificers. Culturally, the ‘Aashta are the most ruthless of the clans and this can lead to characters with evil alignments, though this is driven more by a lack of mercy than by wanton cruelty; like followers of the Mockery, an ‘Aashta will do whatever it takes to achieve victory. Due to its proximity to Droaam, the people of Patrahk’n speak traditional Goblin rather than Azhani, as well as learning Common as a trade language; however, ‘Aashta from the west may prefer Azhani.

Triumvir. Khandar’aashta is bold and charismatic. He is extremely ambitious and is constantly pushing his fellow Triumvirs, seeking to expand the power of Tharashk even if it strains their relations with the rest of the Twelve. Khandar is a follower of the Old Ways; it’s up to the DM to decide if he’s a Whisperer, pursuing the Inner Sun, or if he’s tied to a different and more sinister tradition. While he is ruthless when it comes to expanding the power of the house, he does believe in the union and wants to see all the clans prosper.

Lesser Clans. Overall, the ‘Aashta have no great love of subterfuge. When they need such schemes, they turn to the ‘Arrna, a lesser clan who produces more rogues than rangers. While they are just as aggressive as the ‘Aashta, the ‘Aarna love intrigues and fighting with words as well as blades. The Istaaran are devoted Whisperers and skilled alchemists; they have a great love of poisons and have helped to produce nonlethal toxins to help bounty hunters bring down their prey. The ‘Oorac are a small clan known for producing aberrant dragonmarks and sorcerers; before the union they were often persecuted, but ‘Aashta shields them.

That’s all for now. I’m pressed for time and likely won’t be able to answer questions on this topic. Meanwhile, if you’re interested in shaping the topic of the NEXT article, there’s just four hours left (as of this posting) in the Patreon poll to choose it; at the moment it’s neck and neck between an exploration of Sky Piracy in Khorvaire and my suggestions for drawing players into the world and developing interesting Eberron characters in Session Zero. In addition, tomorrow I’ll be posting the challenge that will determine which Threshold patrons play in my next online adventure. If you want to be a part of any of that, check out my Patreon!

As time permits, I like to answer interesting questions posed by my Patreon supporters. This month, a number of questions circled around the same topic—how would I integrate gem dragons and gem dragonborn into my Eberron? In adding anything new to the setting, by question is always how it makes the story more interesting. I don’t want to just drop gem dragons into Argonnessen and say they’ve always been there; I want them to change the story in an interesting way, to surprise players or give them something new to think about. So here’s what I would do.

Eberron as we know it isn’t the first incarnation of the prime material plane. We don’t know how many times reality has fundamentally shifted, jumping to a new rat in the maze of reality. But we know of one previous incarnation because of its survivors. When their reality was on the brink of destruction, a rag-tag fleet of Gith vessels escaped into the astral plane. These survivors split into two cultures, with the Githzerai dwelling in vast monasteries in Kythri and the Githyanki mooring their city-ships in the astral plane. The transition of realities is a difficult thing to map to time. For us, our reality has always existed, going back to the dawn of creation. For the Gith, the loss of their world is still a thing some hold in living memory. They are hardened survivors. Some crave revenge on the daelkyr, while others are solely concerned with the survival of their people. But the Githyanki aren’t the only survivors of their reality. It was an amethyst greatwyrm who helped the Gith fleet break the walls of space, and a small host of dragons accompanied the survivors into their astral exile. But the dragons aren’t like the metallic and chromatic dragons of the world that we know. They are the gem dragons.

The Progenitors are constants across all versions of the material plane. They created the planar structure of reality, and the material plane is the end result of their labors. The Eberron of the Gith—let’s call it “Githberron”—started with the same primordial struggle. In the current Eberron, the dragons are said to have formed when Siberys’s blood fell onto Eberron. In Githberron, Khyber didn’t tear apart Siberys’s body; she shattered his mind. The gem dragons believed that fragments of Siberys’s consciousness were scattered through reality, and they sought to reunite these shards; just as arcane magic is said to be the blood of Siberys in Eberron, in Githberron psionic energy is called the dream of Siberys.

Where the dragons of our Eberron are concentrated in Argonnessen, the dragons of Githberron were spread across their world. However, they were culturally connected through a telepathic construct—a vast metaconcert, which they believed was a step toward reuniting the shattered Siberys. They called this psychic nation Sardior. So rather than Sardior being another Progenitor, Sardior was their answer to Argonnessen—and they believe it is the soul of Siberys. This idea involves a small but crucial chance to the gem stat block, which is that I’d add Trance (as the elf racial trait) to all gem dragons. When trancing, gem dragons would project their consciousness into Sardior. Today the survivors yearn to recreate Sardior, and each gem dragon carries their own piece of it within their mind; however, I’m inclined to say that there just aren’t enough of them to sustain a global (let alone extraplanar) metaconcert. Two gem dragons in the same place might be able to link their minds when they trance, to dwell together in a sliver of Sardior. But to truly restore the dream of Siberys, they need more dragons. But there’s a catch to that…

In modern Eberron, dragons reproduce as other creatures do. My gem dragons of Sardior, on the other hand, use one of the other methods described in Fizban’s Treasury of Dragons:

Enlightened non-dragons (most often Humanoids) are transformed into dragon eggs when they die, when they experience profound enlightenment… Humanoids and dragons alike understand the transformation to be a transition into a higher state of existence.

The gem dragons of Sardior weren’t born in isolation; they are the evolved, transcendent forms of other denizens of Githberron. This means that they have a fundamentally different relationship with humanoids than the dragons of Argonnessen. In the current Eberron, dragons see humanoids much like mice; useful for experiments, but don’t feel bad if you have to exterminate them, and isn’t it cute when they think they’re dragons. By contrast, in the Gith Eberron, dragons all evolved from humanoids, meaning both that they have memories of their humanoid existence and that they rely on humanoids to propagate their species. This is one of the key reasons they work with the Gith, even if they don’t especially like the Githyanki raiding. Not only are the Gith the last survivors of their world, they may be the only species capable of producing new gem dragons.

So, what is this process of reproduction and enlightenment? First, it requires a certain degree of psionic aptitude. The dragons see psionic energy as the dream of Siberys, and to become a dragon you are essentially drawing the essence of Siberys into yourself; what it means to be a dragon is to become a refined shard of the mind of Siberys. This doesn’t requires all pre-dragons to be full psions, but you need to have some degree of psionic ability, even if it’s just one of the psionic feats from Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything. The second aspect is more ineffable, and it involves unlocking your full potential—becoming the best version of yourself that you can be. In many ways this is similar to the idea of mastering the Divinity Within in the Blood of Vol, or becoming worthy of Ascension to the Undying Court in Aerenal, and it should be just as difficult; it’s usually the work of a lifetime, not something you can rush. And I’d combine the two aspects of the Fizban’s quote—the ascension requires both enlightenment and death, that on death you become a gem dragon egg. So the point is, become enlightened, live your enlightened life, and hope that when you die you’re reborn as a dragon—you don’t want to rush the process unless you’re really sure you’re sufficiently enlightened. It’s definitely something that could happen to a player character, but it would only happen when they die.

A second key aspect of this is the idea that the type of dragon you become reflects the path you walked in life. The reason sapphire dragons are warlike is because they were warriors in their first lives. Amethyst dragons were planar scholars devoted to fighting aberrations before they became dragons; if a Gatekeeper from Eberron became a gem dragon, they’d be amethyst. I’m inclined to say that some of the character’s original memories and skills are lost in the process of draconic ascension, since it would be a significant change to say that every gem wyrmling has the skills of a mortal paragon—but the essence of that first life remains and guides the dragon moving forward. While the wyrmling may not have the full skills of the mortal seed, they have its wisdom and determination, the experience of a life well lived.

In my campaign, there are less than a hundred dragons of Sardior in the current reality. They have a single greatwyrm—an amethyst dragon who played a crucual role in helping the Gith escape their doomed reality and who generally resides at and protects Tu’narath in the astral plane. But again, each gem dragons—even the Wyrmlings—has a rich story of a prior life. Some were Gith warriors who fought against the daelkyr. Some were sages or scholars. In building an encounter with a gem dragon, the first question for the DM should be who were they before they became a dragon?

Gem dragons work with the Gith—both Githzerai and Githyanki—for many reasons. Many of the dragons were Gith before their ascension (though there were many other humanoid species on their world) and they are the last remnant of their lost world. Beyond that, the dragons yearn to recreate Sardior, and the dragons don’t yet know if it’s possible for humanoids of this reality to undergo draconic ascension; the Gith may be the only source of new gem dragons. The dragons who join Githyanki on their raids are primarily sapphire dragons, many of whom were Gith warriors in their former lives and who want to keep their people sharp; amethyst dragons are typically found in the monasteries of the Githzerai, helping build their dream of striking at Xoriat. But not all gem dragons work with the Gith. Here’s a number of ways that adventurers could encounter a gem dragon in my Eberron.

While most of these paths are largely benevolent, there’s certainly room for any of these dragons to go down a sinister path. A guardian may place the survival of the Gith above all else, caring nothing for the damage they do to this cracked mirror in pursuit of their goals. A mentor could eliminate students who fail to live up to expectations—or kill them believing that they will become dragon eggs, only to discover that they weren’t ready.

A key question is how Argonnessen interacts with gem dragons, and whether gem dragons are vulnerable to the influence of the Daughter of Khyber. Given that they are from an alien reality and are so different in how they are formed, I am inclined to say both that gem dragons aren’t affected by the Daughter of Khyber and also that they don’t show up in the Draconic Prophecy. With this in mind, in my campaign, Argonnessen doesn’t know much about gem dragons. Because they can and have spontaneously manifested over the course of history, Argonnessen dismisses isolated encounters with gem dragons as fluke occurrences, thinking they’re much like a draconic version of tieflings or aasimar; they haven’t yet realized that there is a civilization of gem dragons active in the world. This gives player characters the opportunity to have a front row seat for the full first and open contact between Sardior and Argonnessen. The Sardior dragons have been studying Argonnessen via their draconic observers and dealing with a few individual sympathetic dragons, but they haven’t yet dealt with the Conclave or the Chamber—and adventurers could be a part of this event when it occurs. Will the Conclave work with these alien dragons? Or will they view them as a threat that should be eliminated? A second plot thread I might explore is the idea that the gem dragons aren’t as vulnerable to the Daughter of Khyber as native dragons, but that they aren’t immune to her influence… that a gem dragon who remains on Eberron and exercises its power might slowly be corrupted by the overlord, turning a valued ally into an enemy. The main point is that I’d rather have these things occur as part of the story the player characters are involved in than to be something that occurred long ago.

One important question is how the dragons of Sardior interact with the psi-active forces of the current Eberron, notably Adarans, kalashtar, and the Dreaming Dark. If psionic talent is a cornerstone of the evolution into a gem dragon the kalashtar could be natural allies for Sardior; the Adaran shroud would also make Adar a compelling place to have a secure Gith creche for raising children. On the other hand, it’s possible that because kalashtar psionic talent is tied to an alien spirit that the kalashtar are a spiritual dead end or at least would have MORE trouble ascending than other humanoids. It could be that Adar is already home to one or more native gem dragons; it could be very interesting to reveal that there’s always been a gem greatwyrm hidden beneath Adar, helping to protect its people.

On the other side of things, gem dragons might be more interested in Riedra and the Inspired. Could the Hanbalani be hijacked to create a form of Sardior? On the other hand, once the gem dragons have revealed their presence, I could imagine the Dreaming Dark trying to capture and use them; this could be the source of an obsidian dragon.

The main point to me is that I’m always more interested in having interesting things happen NOW than setting them in the past. I’d rather have Adaran or Kalashtar players be actively involved when a Sardior emissary comes to Adar and asks to build a creche than to say that it happened a century ago… though I do love the idea of the revelation that there have always been a few native gem dragons in Adar who have helped to guide and protect the nation!

In my Eberron, gem dragonborn are like gem dragons, in that they aren’t a species that reproduces with others of their kind; they must be created. For these purposes, I’d consider the half-dragon origins suggested in Fizban’s Treasury of Dragons. True Love’s Gift suggests that a bond of love between a dragon and another creature can produce a dragonborn, while Cradle Favor suggests that some gem dragons can transform an unborn child. How and why this could occur would depend on the nature of the dragon sharing their power. A guardian dragon could cultivate a squad of dragonborn soldiers. Likewise, a mentor could cultivate a small family of dragonborn to help with its mission. On the other hand, a secretive hedonist or mentor could produce a dragonborn through a bond of love, with the child and their mother never knowing the true nature of the draconic godparent. On the other hand, Fizban’s offers other possible paths to becoming a half-dragon… notably, the idea that “A creature that bathes in or drinks the blood of a dragon can sometimes be transformed into a half-dragon.” I wouldn’t make this reliable or easy technique… but it leaves the possibility that some of the Draleus Tairn hunt gem dragons for this reason, or that a dying gem dragon might choose to give the last power of its blood to a humanoid that finds it.

This provides a range of options for a gem dragonborn player character. If you’re tied to a guardian, it means that you have an active connection to the Sardior survivors and a Gith vessel. Why have you left your ship? Have you been exiled for some crime, and seek to clear your name? Do you have a specific mission, whether diplomatic or searching for a particular artifact? If you’re tied to a mentor, you could have a relationship with your draconic benefactor not unlike that of a warlock and their patron; your dragon seeks to gather information and to help elevate humaniodity, and you are their eyes and hands. On the other hand, it could be that you were born as a gem dragonborn but don’t know why—that part of your quest is to discover the dragon who transformed you and to learn why.

Given my theory of Githberron, one might ask what this means for Gith player characters. Are all Githyanki survivors of Githberron? Do all Gith have to have a connection to the Astral or to Kythri? A few thoughts…

The timeless nature of the astral plane means that you could play a Githyanki character who’s a survivor of the lost world. Part of the idea of Githberron/Sardior is that psionic energy was more abundant there, so you could justify being a low-level character by saying that you were a more powerful psion in your own world and part of the reason you’re traveling is to learn to work with the lesser energies of this one. With that said, the Githyanki do want to continue to grow their population; in this article I suggest the existence of creche ships that serve this purpose. I imagine adolescent Githyanki having a sort of rumspringa period—they have to be out of the astral until they physically mature, and some ships might encourage their youths to explore the material plane in this time, learning about the wider world, honing their skills, and making potential allies. Meanwhile, Kythri ISN’T timeless—which among other things suggests that the only Githzerai who personally remember Githberron are monks who’ve mastered some form of the Timeless Body technique (which I’d personally allow some Githzerai NPCs to do even if they don’t have all the other powers of a 15th level monk). On the other hand, because we are dealing with events that defy the concept of linear time, if it suits the story a DM could decide that from the perspective of the Gith, it’s only actually been a few decades since Githberron was lost! Either way, I could also see the Githzerai having a wandering period where their adolescents experience life in the material plane, to understand existence beyond Kythri.

In any case, I would say that all Gith have a connection to either a city-ship or a monastery. So as a Gith, why might you be an adventurer? A few ideas…

That’s all for now! I don’t have time to answer many questions on this article, but feel free to discuss your ideas and ways you’ve used gem dragons or Gith in the comments. If you want to see more of these articles, to have a chance to choose future topics, or to play in my ongoing online Eberron campaign, check out my Patreon!

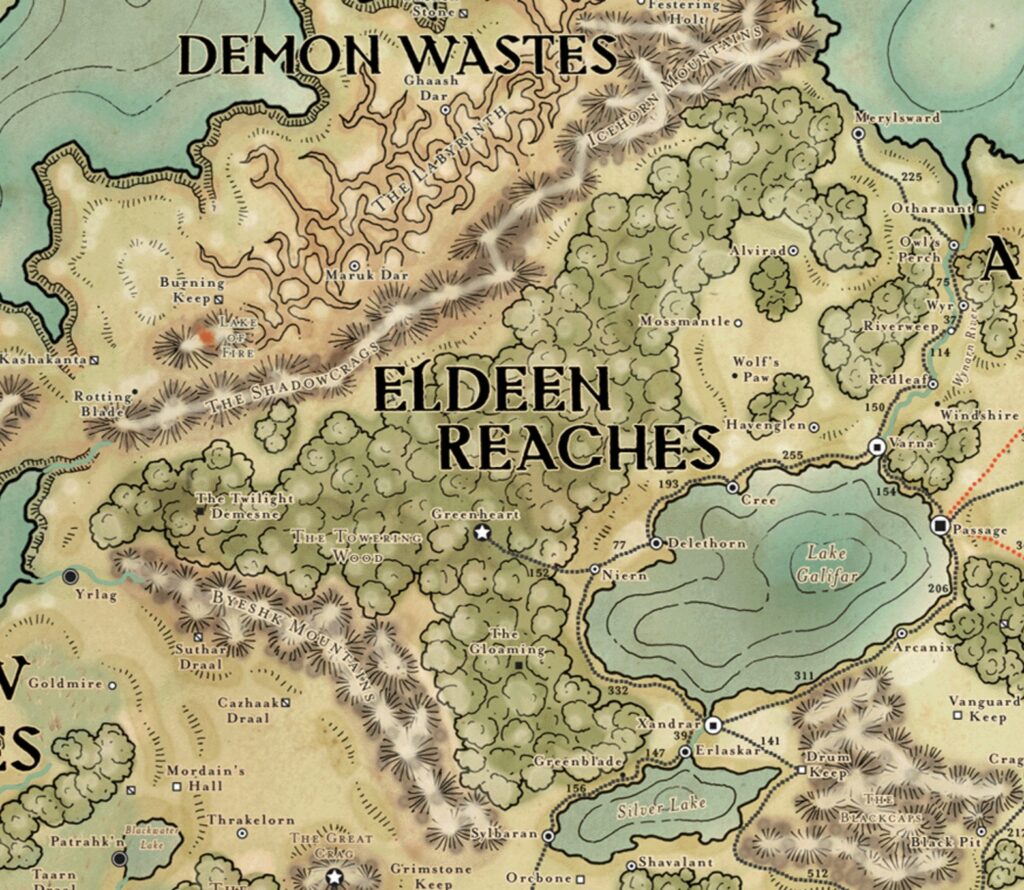

These people fall into two distinct cultures: the farming folk of the eastern plains and the people of the woods. The farmers live on the eastern edge of the Towering Wood. Their ancestors were citizens of Aundair, but their grandparents and great-grandparents turned against the lords of Aundair during the Last War, when the princes of Galifar abandoned them. The plains folk live simple lives, but they are rugged and proud. Most have taken up the beliefs of the druids, and villages have druid advisors. The people of the woods hid from the eyes of Galifar, and most prefer the solitude of the Towering Wood to the bustle of the Five Nations. Shifters and centaurs sometimes live in their own isolated tribes, but most forest folk prefer to live in small mixed communities—human, elf, and shifter living side by side. They follow the faith of one of the druid sects, but only the most exceptional actually become druids or rangers, joining the patrols that guard woods and plains alike.

Player’s Guide to Eberron

The “Eldeen Reaches” has its roots in early Common and Druidic; it can be translated as “The Old Land” or, perhaps, “The Oldest Land.” The term has been used since the earliest days of the Five Nations, but until the Last War it wasn’t the name of a nation; it primarily referred to the land beyond civilization. The people who actually lived in this vast woodland region called their home the Towering Wood, and most still do. It was only in the midst of the Last War that the Eldeen Reaches became a nation, and that nation was and is something entirely new—the fusion of the traditions of former Aundairians with the shifters and druidic initiates of the Towering Wood. A crucial point is that the former Aundairians didn’t simply adopt the traditions of the Woodfolk, because the people of the Wood weren’t themselves united and besides, many of the woodland traditions couldn’t be directly applied to the agricultural lands of the east. The Wardens of the Wood helped the people of the farmlands secede from Aundair—and then, they worked together to build something entirely new for both of them. While the Eldeen Reaches are now a nation, more than anything they are an experiment, one that is very much still in progress.

Much has been written about the Eldeen Reaches in the present day, but I want to explore the history of the Reaches and of the Towering Wood—because the past can shed vital light on the present and on what the world within the Wood actually looks like.

The Towering Wood is ancient, and not even the trees know all of its secrets. But someone who studies the tales of the Moonspeaker druids, the chants of the Ghaash’kala, and the long-lost records of Dhakaan may piece together this tale of the Wood—a tale that may even be true.

The Towering Wood is as old as the world. Some say the greatpines were the first trees Eberron created, that the Wood was the first forest. In these tales, the Woods were home to the first humanoids, the Ur-Oc… the species we now know as orcs. Tale or truth, the archaeological record shows that orcs were once found across the west coast of Khorvaire, from the Shadow Marches to the Demon Wastes. But the first age was no time of peace. The Towering Wood may have been the first forest created by Eberron, but it was quickly claimed and corrupted by one of the vile children of Khyber—an archfiend known as the Wild Heart. From the Towering Wood, the Wild Heart fought ceaselessly with other overlords; its greatest rival was the Rage of War, Rak Tulkhesh, who held the Shadowcrags and the lands beyond. There are many stories that could be told of this time, tales of the endless battles between gnoll and orc, of how the orcs of the north were freed by the First Light and witnessed the birth of the Binding Flame. There are stories to be told of the dragons, of how they came to Khorvaire after the binding and how the Daughter of Khyber shattered all that they created. But these tales are in the deep and distant past, and our interest lies closer to the present. In the “Age of Monsters,” the goblins of Dhakaan became the greatest power in Khorvaire. They drove the orcs into harsh and dangerous lands, places the goblins didn’t want—high mountains, deep swamps, the wild and untamed woods. The orcs cared little, for they loved these primal lands. And so as the empire expanded, the orcs prospered in the Towering Wood. They lived in harmony with the fey of the Twilight Demesne, and kept the malevolent Gloaming at bay. They raised no cities and forged no empires, and felt no need for either.

So how is it that when humanity came to Khorvaire, there were no orcs in the Towering Wood?

A student of arcana might leap to a conclusion. Surely, it was the daelkyr! And in part it was. When the forces of Xoriat boiled into the world, the Twister of Roots sunk its tendrils deep into the Towering Wood. But the Gatekeepers—orcs druids, trained by the dragon Vvaraak—came north to the Towering Wood and shared their secret knowledge with their cousins. Together, druidic orc and Dhakaani goblin overcame the horrors of the daelkyr and drove the lords of Xoriat into the darkness. The daelkyr were bound in Khyber by primal seals, which took many forms. Some say that the seals had to match to the nature of the daelkyr. The Twister of Roots couldn’t be bound with stone or steel; Avassh could only be held at bay by a living seal of root and leaf, and so it was that the druids created the Eldeen Ada—Druidic for, essentially, the first trees—imbuing a handful of trees with sentience and primal power. The greatest of these, and the only one known in the wider world, is the Guardian of the Greenheart, the Great Druid Oalian. But there are other guardian trees spread across the Towering Wood. Some guide their own communities of druids and rangers. Others prefer the company of dryads or elemental spirits. At least one has grown bitter and despises humanoids. The Eldeen Ada have existed for thousands of years, and they have been an invaluable source of primal wisdom. If this tale is true, they are more than that. Oalian is one element of the living seal that keeps Avassh in Khyber. So it wasn’t the Twister of Roots that destroyed the orcs of the Towering Wood. And yet, a thousand years later, the Eldeen Ada would be the only remnant of those orcs. When humanity came to Khorvaire, the Wood was the domain of scattered shifter tribes and feral gnolls. What happened?

The tales of the shifter Moonspeakers never say how the shifters came to Khorvaire. They speak only of a time of chaos and terror, a time when shifters were feral beasts. According to this myth, it was Olarune who taught the first shifters to master the beast within, and who trained the first Moonspeakers. A historian who carefully traces these stories and compares them with the Dhakaani ruins in what is now the Eldeen Reaches could come to a clear conclusion: soon after the daelkyr were bound, something happened in the Towering Wood that utterly obliterated both the orcish culture within the Wood and the Imperial cities just beyond it. Centuries later, a handful of shifter tribes are living in the Wood, with tales of the moon goddess leading them out of terror. What could do such a thing? Why, the same power that almost did it again, thousands of years later. The evidence suggests that the Wild Heart broke free from its bonds and held dominion over what is now the Eldeen Reaches, possibly for centuries. All civilizations in the region were obliterated. Those humanoids that survived were taken by the Curse of the Wild Heart, becoming cruel, predatory lycanthropes driven by the will of the overlord. Somehow, centuries later, something broke this cycle. Something new emerged among the cursed victims of the Wild Heart—champions wielding primal power, who somehow returned the overlord to his bonds. And when peace returned to the Wood, there were no orcs left—there were only shifters.