These people fall into two distinct cultures: the farming folk of the eastern plains and the people of the woods. The farmers live on the eastern edge of the Towering Wood. Their ancestors were citizens of Aundair, but their grandparents and great-grandparents turned against the lords of Aundair during the Last War, when the princes of Galifar abandoned them. The plains folk live simple lives, but they are rugged and proud. Most have taken up the beliefs of the druids, and villages have druid advisors. The people of the woods hid from the eyes of Galifar, and most prefer the solitude of the Towering Wood to the bustle of the Five Nations. Shifters and centaurs sometimes live in their own isolated tribes, but most forest folk prefer to live in small mixed communities—human, elf, and shifter living side by side. They follow the faith of one of the druid sects, but only the most exceptional actually become druids or rangers, joining the patrols that guard woods and plains alike.

Player’s Guide to Eberron

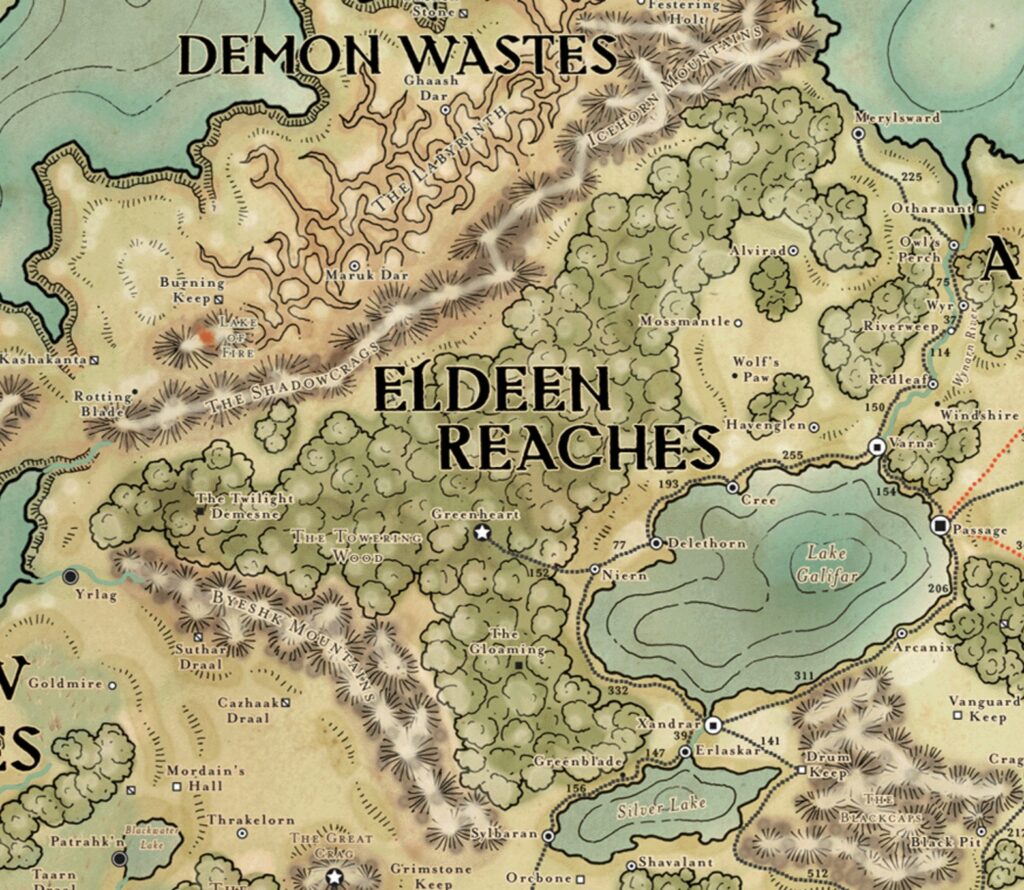

The “Eldeen Reaches” has its roots in early Common and Druidic; it can be translated as “The Old Land” or, perhaps, “The Oldest Land.” The term has been used since the earliest days of the Five Nations, but until the Last War it wasn’t the name of a nation; it primarily referred to the land beyond civilization. The people who actually lived in this vast woodland region called their home the Towering Wood, and most still do. It was only in the midst of the Last War that the Eldeen Reaches became a nation, and that nation was and is something entirely new—the fusion of the traditions of former Aundairians with the shifters and druidic initiates of the Towering Wood. A crucial point is that the former Aundairians didn’t simply adopt the traditions of the Woodfolk, because the people of the Wood weren’t themselves united and besides, many of the woodland traditions couldn’t be directly applied to the agricultural lands of the east. The Wardens of the Wood helped the people of the farmlands secede from Aundair—and then, they worked together to build something entirely new for both of them. While the Eldeen Reaches are now a nation, more than anything they are an experiment, one that is very much still in progress.

Much has been written about the Eldeen Reaches in the present day, but I want to explore the history of the Reaches and of the Towering Wood—because the past can shed vital light on the present and on what the world within the Wood actually looks like.

The Forgotten Roots of the Towering Wood

The Towering Wood is ancient, and not even the trees know all of its secrets. But someone who studies the tales of the Moonspeaker druids, the chants of the Ghaash’kala, and the long-lost records of Dhakaan may piece together this tale of the Wood—a tale that may even be true.

The Towering Wood is as old as the world. Some say the greatpines were the first trees Eberron created, that the Wood was the first forest. In these tales, the Woods were home to the first humanoids, the Ur-Oc… the species we now know as orcs. Tale or truth, the archaeological record shows that orcs were once found across the west coast of Khorvaire, from the Shadow Marches to the Demon Wastes. But the first age was no time of peace. The Towering Wood may have been the first forest created by Eberron, but it was quickly claimed and corrupted by one of the vile children of Khyber—an archfiend known as the Wild Heart. From the Towering Wood, the Wild Heart fought ceaselessly with other overlords; its greatest rival was the Rage of War, Rak Tulkhesh, who held the Shadowcrags and the lands beyond. There are many stories that could be told of this time, tales of the endless battles between gnoll and orc, of how the orcs of the north were freed by the First Light and witnessed the birth of the Binding Flame. There are stories to be told of the dragons, of how they came to Khorvaire after the binding and how the Daughter of Khyber shattered all that they created. But these tales are in the deep and distant past, and our interest lies closer to the present. In the “Age of Monsters,” the goblins of Dhakaan became the greatest power in Khorvaire. They drove the orcs into harsh and dangerous lands, places the goblins didn’t want—high mountains, deep swamps, the wild and untamed woods. The orcs cared little, for they loved these primal lands. And so as the empire expanded, the orcs prospered in the Towering Wood. They lived in harmony with the fey of the Twilight Demesne, and kept the malevolent Gloaming at bay. They raised no cities and forged no empires, and felt no need for either.

So how is it that when humanity came to Khorvaire, there were no orcs in the Towering Wood?

A student of arcana might leap to a conclusion. Surely, it was the daelkyr! And in part it was. When the forces of Xoriat boiled into the world, the Twister of Roots sunk its tendrils deep into the Towering Wood. But the Gatekeepers—orcs druids, trained by the dragon Vvaraak—came north to the Towering Wood and shared their secret knowledge with their cousins. Together, druidic orc and Dhakaani goblin overcame the horrors of the daelkyr and drove the lords of Xoriat into the darkness. The daelkyr were bound in Khyber by primal seals, which took many forms. Some say that the seals had to match to the nature of the daelkyr. The Twister of Roots couldn’t be bound with stone or steel; Avassh could only be held at bay by a living seal of root and leaf, and so it was that the druids created the Eldeen Ada—Druidic for, essentially, the first trees—imbuing a handful of trees with sentience and primal power. The greatest of these, and the only one known in the wider world, is the Guardian of the Greenheart, the Great Druid Oalian. But there are other guardian trees spread across the Towering Wood. Some guide their own communities of druids and rangers. Others prefer the company of dryads or elemental spirits. At least one has grown bitter and despises humanoids. The Eldeen Ada have existed for thousands of years, and they have been an invaluable source of primal wisdom. If this tale is true, they are more than that. Oalian is one element of the living seal that keeps Avassh in Khyber. So it wasn’t the Twister of Roots that destroyed the orcs of the Towering Wood. And yet, a thousand years later, the Eldeen Ada would be the only remnant of those orcs. When humanity came to Khorvaire, the Wood was the domain of scattered shifter tribes and feral gnolls. What happened?

The tales of the shifter Moonspeakers never say how the shifters came to Khorvaire. They speak only of a time of chaos and terror, a time when shifters were feral beasts. According to this myth, it was Olarune who taught the first shifters to master the beast within, and who trained the first Moonspeakers. A historian who carefully traces these stories and compares them with the Dhakaani ruins in what is now the Eldeen Reaches could come to a clear conclusion: soon after the daelkyr were bound, something happened in the Towering Wood that utterly obliterated both the orcish culture within the Wood and the Imperial cities just beyond it. Centuries later, a handful of shifter tribes are living in the Wood, with tales of the moon goddess leading them out of terror. What could do such a thing? Why, the same power that almost did it again, thousands of years later. The evidence suggests that the Wild Heart broke free from its bonds and held dominion over what is now the Eldeen Reaches, possibly for centuries. All civilizations in the region were obliterated. Those humanoids that survived were taken by the Curse of the Wild Heart, becoming cruel, predatory lycanthropes driven by the will of the overlord. Somehow, centuries later, something broke this cycle. Something new emerged among the cursed victims of the Wild Heart—champions wielding primal power, who somehow returned the overlord to his bonds. And when peace returned to the Wood, there were no orcs left—there were only shifters.

This is a possibility, not absolute fact; other myths suggest that the first lycanthropes were cursed shifters, not the other way around. But this story explains the dramatic disappearance of the orcs and orcish culture in the region, and is is echoed by the events of the Silver Crusade. It’s simple fact that the overlords can escape their bonds; the near-release of Bel Shalor threw Thrane into chaos in the Year of Blood and Fire. Thrane’s travails are well documented because the civilization that dealt with it survived and still exists today. This dominion of the Wild Heart came as the Dhakaani Empire was collapsing and contributed to that collapse, and the orcs of the Towering Wood were completely destroyed by it. The only survivors of that time are the trees themselves. Oalian surely knows what became of the orcs, but in the few times they’ve been asked, they’ve said there are secrets that cannot be unspoken. This echoes the fact that we don’t know how the curse was broken in the Silver Crusade… that there may have been a reason that the details of the victory were never shared and celebrated. Breaking the fourth wall for a moment, there’s a practical reason for this. If, as a DM, you decide to make the Wild Heart part of your campaign, one of the crucial challenges for the player characters will be finding out how it was defeated before and why those details were hidden. WHY won’t Oalian discuss it? Would sharing that knowledge widely somehow help the Wild Heart? Could it be something even stranger: in order to bind the Wild Heart, a group of templars and Moonspeakers had to become a new form of lycanthrope—another form of the living seal—and that to this day there is a secret group of lycanthropes at the heart of the Church of the Silver Flame, somehow evading all forms of divination? Have all the Keepers since that time been lycanthropes? Ultimately, the point is that the Wild Heart has been released before, and the eradication of the orcs and goblins of the region shows the stakes: fully unleashed, the Wild Heart would destroy the people of the Eldeen Reaches and Aundair. But should this threat arise again, people will have to learn how the Overlord was defeated before and why those involved kept those details hidden.

This story contains another important secret: who—or what—is Olarune? In the Moonspeaker tales, Olarune is the moon herself, descended from the heavens to guide the shifters and to free them from a time of chaos. The implication is that these proto-shifters were natural lycanthropes controlled by the Curse of the Wild Heart—which removes free will and enforces cruel, predatory behavior—and that “Olarune” somehow overcame the curse, while also making them shifters. Rather than being slaves to predatory instincts, they “mastered the beast within.” Who would and could do such a thing? One simple answer is a dragon. The dragon Vvaraak taught the first gatekeepers, and Olarune is said to have taught the first Moonspeakers. Could Olarune have been another Child of Eberron—or even Vvaraak herself, returned from a period of stasis? Another possibility is that Olarune was an archfey who came to the Towering Woods through the Twilight Demesne—that shifters may still have a literal faerie godmother in Thelanis. Perhaps Olarune was a manifestation of Eberron itself, a force of primal power. Or, just possibly, Olarune was a player character of her age—not an avatar of Eberron, but a natural lycanthrope who somehow channeled the power of Eberron, much as Tira Miron channeled the power of the Silver Flame. Again, this is a decision for each DM to make for themselves, should they decide to tell the story. The question is whether Olarune still exists—whether adventurers can find her in Thelanis or in Argonnessen, whether druids can reach her by communing with nature, or whether she was just a mortal—in which case it might be possible for a mortal champion of this age to assume her mantle.

The Coming of Humanity

Once upon a time, an orc culture was spread across the Towering Wood. When humanity came to what is now Aundair, the Towering Wood was inhabited by scattered shifter tribes; aside from the absence of orcs, the shifter population was far lower than that of the ancient orcs of the region. There’s two reasons for this. The first is understanding the desires of the Wild Heart. Look to the Silver Crusade: the overlord didn’t simply turn ALL of the people of the Towering Wood into lycanthropes. He turned some of the denizens into lycanthropes, and then set them on their former friends and neighbors. The Wild Heart isn’t in any way a spirit of nature; he delights in savagery and the prey’s fear of the predator. If and when he was released before, he created servants and forced them to prey upon their former people. A grim possibility is that the reason he was eventually rebound—the reason Olarune was able to create the shifters—was because there were no innocents left to hunt, and that this weakened the overlord.

So first of all, the initial shifter population was just a fraction of the former orcs. The second point is that the Towering Wood was far more dangerous than it had been in the past. At the start of the Age of Monsters, the Wild Heart had been bound for tens of thousands of years, and the daelkyr had yet to arrive. The Wood as it exists today—and as humanity first found it— is quite a different place. Consider…

- The Twister of Roots is the daelkyr that has the greatest influence in the Towering Wood, but Dyrrn the Corruptor touches it as well. While the daelkyr are bound, their minions and their influence can affect the surface. As noted in the Player’s Guide to Eberron, “For every dryad, there is a dolgrim; for every unicorn, there is a runehound.” Cults of the Dragon Below can manifest at any time, and countless denizens of the Wood have been corrupted by the daelkyr over the ages.

- The Wild Heart held dominion over the region for centuries before being rebound, and its power rose again during the Silver Crusade. The scars of these conflicts remain. The woods are filled with dire and horrid beasts that act with unnatural aggression and cruelty. There are bands of feral gnolls still driven by the hunger of the Wild Heart. It seems that the power of the Curse of the Wild Heart may be growing again, and it could well be that the bite of a horrid beast could inflict an innocent with the curse.

All of this is added to the effects of powerful manifest zones… primarily to Lamannia and Thelanis, but with notable exceptions such as the Gloaming. Beyond this, despite their best efforts the Ghaash’kala can’t contain every element of evil that seeks to cross the Labyrinth; there are always a few fiends roaming the northern woods. The crucial point is that the Towering Wood are dangerous. In his Chronicle of Thaliost, the sage Dalen Book wrote that “The world ends at the Towering Wood.” The human settlers interacted with shifters on the edge of the Wood—sometimes trading, sometimes fighting—but after a few efforts they settled on the pleasant lands they called Thaliost and abandoned the idea of claiming the “Eldeen Reaches.” However, there were always some people who heard the call of the Wood.

This brings us to the druid sects we know today. The bulk of the shifter tribes follow the Moonspeaker tradition. But there were always a few drawn to different paths. Largely, these were tied to region—and most often to the guidance of one of the ancient trees. The Children of Winter have always been based in the Gloaming and helped to contain this sinister power. The Greensingers walk the edge of the Twilight Demesne. The Ashbound protect the northern Reaches from the fiends that cross the mountains. So the first druids of all of these sects were shifters, but slowly, new initiates trickled in from the newcomers settling to the east. It was at this point that Oalian formed the Wardens of the Woods, to protect the people of Thaliost from the Wood and to protect the Wood from civilization. The Wardens helped to mediate disputes between shifters and settlers, and earned the respect of both sides.

As centuries passed, the shifters of the Towering Wood maintained their traditions, while the people of Thaliost continued to expand and grow. But on the whole, it remained as Dalen Book had said; for all intents and purposes, civilization came to an end at the edge of the Towering Wood.

The Silver Crusade and the Lycanthropic Purge

Thaliost became Galifar, and under Galifar the Towering Wood and the land around it were all declared to be part of Aundair. The Eldeen Reaches was a term used to refer to all the lands west of the Wynarn River. It was a region of Aundair, known for its farmland—but it was on the edge of civilization and lacked the sophistication of Fairhaven or Thaliost, the arcane elegance that had come to define Aundairian culture. The nobles largely ignored reports of gnoll reavers, and the few times that the Carrion Tribes breached the Labyrinth in force, little was done until they threatened Varna. This disdain can be clearly seen in the ninth century. When werewolves terrorized the farmers of the Reaches, the lords of Aundair ignored their pleas for aid. It was the Church of the Silver Flame that responded, by launching the Silver Crusade. After a bad start based on ignorance and the work of cunning wererats, a tenuous alliance was formed between the templars and the inhabitants of the Towering Wood. Templars needed the support of shifter villages to carry the campaign deeper into the Wood, and it was only by working together that Moonspeakers and templars were able to break the power of the Wild Heart. This could have been a moment that forged a strong and lasting bond between the two forces. But for whatever reason, the details of that victory weren’t shared. The templars of Thrane left the region, and only the Pure Flame remained—Aundairians who embraced the Flame as a weapon, and who sought an outlet for their pain and someone to blame for their losses and suffering. Under the guise of hunting down every last lycanthrope—ultimately, an impossible task, as the lingering power of the Wild Heart can always create more—the Pure Flame carried out decades of cruel purges that drove a lasting wedge between shifters and the church.

As historians often focus on the tragedy of the Purge, there’s another important aspect of this period that’s often overlooked. The Pure Flame arose because Aundairians embraced the force they saw as saving them from the apocalyptic threat. But it wasn’t only the templars who fought that battle. Some farmers fought alongside shifters; others were saved from death by the druids and rangers of the woods, most notably the Wardens of the Wood. Even as some farmers embraced the Pure Flame and hunted for imaginary werewolves, others embraced the druidic mysteries and left their fields to serve as Wardens of the Wood. This moment laid the cornerstone for the modern Eldeen Reaches, increasing contact and interaction between the farmers and the Woodfolk and increasing the numbers of all of the Eldeen sects. One reason the people of the Five Nations know so little about the druids is because before the Silver Crusade there just weren’t enough of them to push beyond the Reaches. The Ashbound are an especially good example of this. TODAY they are infamous for raiding Dragonmarked facilities and sabotaging airships. Prior to the last century, they didn’t have enough contact to even know about the Dragonmarked Houses, let alone the numbers to plan such raids. Even as followers of the Pure Flame pressed deeper into the Wood in pursuit of their purge, other Aundairians learned about the primal mysteries. So all of the sects grew in power, the Wardens of the Wood most of all.

It’s important to understand that at this time, the people of the Wood weren’t in any way a NATION. If the Moonspeaker shifters had been united, they might have joined together to wipe out the Pure Flame; but they weren’t united. Some chose to retreat deeper into the woods; others fought the Pure Flame, played into the zealots’ narrative. Eventually the Wardens of the Wood worked with the Moonspeakers and other sects to draw a line the Pure Flame couldn’t cross, and it was this that brought the Purge to an end. Some of the people of Western Aundair were grateful to the Wardens, while to the followers of the Pure Flame it was proof than no druid could be trusted.

The Eldeen Secession

The Last War proved to be the undoing of the old order. As the conflict intensified, Aundair pulled its forces back to protect its heartland and eastern borders, leaving the Eldeen Reaches to fend for themselves. Bandit lords sponsored by Karrnath and the Lhazaar Principalities harried the farms west of the Wynarn River, using the forest as a base and staging ground. In the south, Brelish troops crossed the Silver Lake to occupy Sylbaran, Greenblade, and Erlaskar. As things went from bad to worse, an army of druids and rangers emerged from the forest. In 956 YK, the Wardens of the Wood rallied the farmers and peasants, crushing the bandit army before it knew what was happening. With order restored in the north, the Wardens turned their attention to the south. In 959 YK, they finally succeeded in driving the Brelish forces back across the lake.

Angry at the Aundairian crown for abandoning them, the people swore allegiance to the Great Druid, breaking all ties with the lords of Aundair and resisting several Aundair attempts to regain control. Since 958 YK, the people of the Eldeen Reaches have considered themselves to be part of an independent nation, and they were finally recognized as such with the signing of the Treaty of Thronehold. It remains to be seen whether Aundair will try to reclaim its old territories now that the Last War has ended.

Eberron Campaign Setting

The lords of eastern Aundair had long ignored the farmers on the edge of civilization, and this pattern continued in the Last War. The Eberron Campaign Setting presents the basic issue. Eastern Aundair looked to the west for taxes, for crops, and for conscripts; but they left the farmers to defend themselves from brigands, gnolls, even Brelish soldiers. For the most part, these were relatively minor incidents—in part because the Wardens of the Wood did act to deal with bandits that sought shelter in the Towering Wood or who came too close to the edge of the forest. But as the war went on, these provocations grew increasingly serious. State-sponsored brigands became better organized and armed… and at least some of these “brigands” were Pure Flame zealots. The Brelish advance across Silver Lake was the last straw.

The Eberron Campaign Setting presents the arrival of the Warden army almost as a surprise, with the farmers saying “What the heck! Let’s sign up with you!” a year later. This is a romantic image, but it oversimplifies things. The ties between the people of the west and the Wardens of the Wood had been growing for over a century, ever since the Silver Crusade. The intervention was the result not only of years of pleas from the east, but also of diplomacy within the Wood, as the Wardens convinced the woodland tribes and the other sects to join their cause. The appearance of the Wardens in 956 YK was carefully planned, and many of the farmers were already prepared to join the fight. The idea of secession was already on the table in 956 YK; it simply took the victories and the show of strength by the Wardens to convince the holdouts to embrace the cause. The Wardens won over a few of the landed nobles, even though it meant relinquishing their titles. Others were driven from their lands—though as most of these lords were already living in the cities of the east, it was easily done.

The Evolving Reaches

In considering with the Eldeen Reaches, it’s important to understand the degree to which the Towering Wood is still vast and untamed; the Player’s Guide to Eberron notes that “humanity barely has a foothold in that fortress of nature.” In many ways, the Towering Woods can be compared to the Lhazaar Principalities; the various sects and tribes respect Oalian and could be rallied again, but they’re spread wide and hold fast to their own traditions. The most unified part of the nation is the fields, because its people were unified as citizens of Aundair. As I said at the start, the Eldeen Reaches are an experiment, where the people of the fields are actively learning how to blend their old ways with the druidic traditions. There are still people in the Reaches who don’t support the new nation and who are rooting for Aundair to reclaim the land; they’re simply enough of a minority that they don’t exert power over any major community. These include followers of the Pure Flame, though many of these folk have moved east to Thaliost, delighted to have an ancient city ruled by one of their own.

The thing to always keep in mind is that the Eldeen Reaches have only existed in this current form for four decades. They’re still learning how to settle disputes and the most effective ways to employ druidic magic in everyday life. So far the Reaches are thriving, and most of the people of the land are proud of what they’ve created. But it’s evolving every day, and the shadows of the Towering Wood are just as dangerous as ever.

WHY DOES THIS MATTER?

As with any lore, it always comes down to the question… why does this actually matter to you, whether as player or DM? There’s a few points to consider here.

First, always consider the separation between the fields and the Wood. The fields are the focus of the great experiment, where the people of cities and villages are integrating the druidic traditions into everyday life. But Varna is far older than the Reaches as a nation. There are people in Varna who are either indifferent to this experiment and even some who actively oppose it. If you’re from one of the cities, where do you stand on this? Are you a fervent supporter of your nation, keen to help it realize its full potential and to serve as a beacon to the world, showing the wisdom of adopting the druidic traditions? Are you working to rally allies against the threat of Aundairian aggression? Or are you indifferent—you’re from the Reaches, but you’re not excited about it? Or are you actively opposed to “the Warden Occupation” and hope to help Aundair reclaim the region? If you’re from the Wood, are you deeply invested in the experiment of the fields, or are you from a deep forest tribe with no interest and little knowledge of the Five Nations?

All of this especially applies to a druid, ranger, or other character with a primal background. If you’re a druid, were you born into the sect or did you come from a family of farmers and choose this path yourself? Keep in mind that the reaches have only been around in their current form for forty years. If you’re an elf, you’re mostly likely older than the nation. Did you fight in the struggle for independence? Were you born in the Wood, or were you raised in Aundair?

As a DM, one of the most crucial things to remember is how mysterious and dangerous the Towering Wood is. As noted in the PGtE, humanity barely has a foothold in that fortress of nature… and the shadows of the wood are home to fiends, aberrations, monstrosities, fey, undead, and more. Neither the ancient orcs nor the Wild Heart built cities, but adventurers could still find ritual sites, cave dwellings, or other relics that reach back to the Age of Monsters or even the Age of Demons. Dhakaani soldiers fought alongside Gatekeeper druids, and there could be an undead dar troop still lost the Gloaming. And while the Gloaming and the Twilight Demesne are MASSIVE manifest zones, there are many, many smaller manifest zones scattered throughout the region. You can potentially encounter fey or undead anywhere in the Wood. The Wardens and the other sects do their best to locate and watch these, and a Thelanian zone might have a resident Greensinger… but again, the Wood is vast.

Next up, keep the events of the Silver Crusade and the Purge in mind. There’s surely remnants of villagers still haunted by innocent shifters slain during the Purge; but you could also find relics of battles where templars and shifters stood side by side. Beyond this, while the power of the curse was broken, the Wild Heart nearly broke free and the remnants of its power can still be felt. There are horrid animals that are crueler and more cunning than any natural beast should be, feral gnolls that are thralls of the Wild Heart, beasts that are actually hosts for fiends, and more. The Wood was also a stronghold of the daelkyr Avassh; you never know when you might stumble upon a cult or relics of the Twister of Roots

A final thing to keep in mind is whether the Eldeen experiment will take a dramatic turn in your campaign. Will Aundair try to reclaim the Reaches? And if so, how will the rest of Khorvaire react? Or is this danger a lurking problem for future generations?

Q&A

While I don’t have time to answer every question people may have about the Eldeen Reaches, I do want to answer some questions posed by my Patreon supporters this month.

Any fiendish forces from the Wastes that bypass the Ghaash’kala will inevitably end up in the Reaches. Given that fiends and Carrion Tribes do sometimes break through, and the Ghaash’kala are ‘too corrupted’ to leave, is there an organization in the Reaches that deals with such incursions?

The critical issue here is to understand the scale of the situation. The Ghaash’kala are able to stop large forces, which is why it’s been centuries since the Carrion Tribes have managed to cross the Labyrinth. But the Labyrinth stretches across hundreds of miles, and individual fiends or small groups of raiders can slip through. And when they do, what they reach is the Towering Woods—hundreds of miles of a land where “humanity barely has a foothold,” and where dolgrims, horrid beasts, feral gnolls and worse things abound.

Essentially, it’s unfeasible for the denizens of the Towering Wood to try to enforce order on regions of the Wood where they don’t actually live. It’s too large and filled with too many threats, and ultimately, what’s the point? Why lay down innocent lives to enforce order on land no one actually wants to use for anything?

So no, there is no organization in the Reaches that attempts to deal with EVERY INCURSION from the Demon Wastes; the fiends that make it across the mountains disappear into the host of threats the Wood has to offer. With that said, there are two organizations that seek to defend occupied territory from fiends. The first of these is the Wardens of the Wood, who have a broad mandate to protect the people of the Reaches from ALL threats (… as well as protecting the Reaches from the people!). and who cover the widest range. Meanwhile, the Ashbound particularly despise fiends, which they consider to be incarnations of unnatural magic; it’s for this reason that the Ashbound are concentrated in the northern woods. So the point is that even the Ashbound don’t try to catch EVERY FIEND that makes it through the Labyrinth. But they remain ever alert within the regions they inhabit, and hunt fiends whenever they find signs of their presence.

A secondary point to keep in mind here is that Eberron is designed to be a world in need of heroes. Rather than saying the Ashbound have a long-established alliance with the Ghaash’kala and work closely together to deal with threats, I’m inclined to say the Ashbound have a feud with the Ghaash’kala based over a misunderstanding that happened centuries ago and never work together. This is exactly the sort of thing that a diplomatic player character could resolve, but it makes it a problem that needs to be fixed if there’s a threat of a mass incursion from the Demon Wastes… as opposed to saying “Oh, no biggie, the Ghaashbound Alliance has it all under control.”

Who are some famous figures from across the Eldeen Reaches (including the area before it was the Reaches)? Any famous heroes or villains or organizers or leaders past or present that the players could point to and say hey, my character is inspired one way or another by this figure?

First and foremost is Oalian themself; initiates of every sect respect the wisdom of the Great Druid. Here’s a few other prominent figures who have been mentioned in canon.

- Bennin Silverclaw is a shifter champion from the time of the Silver Crusade. He’s renowned for playing a crucial role in forging the alliance between an shifters and the templars. He fought alongside the templars during the Crusade and may well have been part of the force that finally broke the power of the Curse. He’s believed to have died pursuing a force of lycanthropes into the Demon Wastes.

- Briar is a Khoravar Greensinger. In the decade leading up the the secession, he roamed the Reaches raising spirits and encouraging people to embrace independence. Even after the secession, he remained active on the Aundair-Eldeen border, rallying the Reachers and embarrassing the Aundairians. He was captured by Aundairian forces in 968 YK, and has spent the last 30 years in a silent cell. Note that this Briar is no relation to Briar of Threshold, and may well have been imprisoned before that Briar was born.

- Faena Graymorn is a Khoravar druid. While Oalian is the spiritual leader of the Wardens, they’re a tree; Faena is the humanoid leader of the sect, conducting important business that requires hands and legs. She played a critical role in the secession and was involved in the negotiations that earned the Reaches recognition at the Treaty of Thronehold. She is a powerful druid; songs are sung about her deeds driving the Brelish from Sylbaran. However, the years are catching up to her. Today she’s primarily an administrator and diplomat; it’s been a decade since she’s called down lightning against a foe.

- Stormclaw is an Ashbound shifter whose strength is legendary throughout the Reaches. He’s said to have crushed fiends with his bare hands, and even to have survived an armwrestling contest with Sora Maenya (before the rise of Droaam). Stormclaw is a bold and ruthless hunter; where his comrade Tasia hunts wizards in Aundair, Stormclaw reserves his wrath for the fiends he tracks in the northern woods.

- Raven is one of the most powerful members of the Children of Winter. Where the Children have long contained the power of the Gloaming, Raven has harnessed it and can wield it in battle. She is one of the voices asserting that the time has come to cleanse the world—that the Mourning is merely the first sign, and that the only path to the new s\Summer lies directly through Winter.

Quite a few more notable members of the sects are mentioned in the Player’s Guide to Eberron; here’s one section that mentions a few other Wardens of the Wood.

Other notable members of the wardens include Root (NG male personality warforged fighter 2/druid 4), a spiritual soldier searching for his place in the natural world; Moselin (NG male human druid 7), advisor to the town of Cree and also an active hunter of aberrations; and Feralyn Wolf-tail (NG female gnome ranger 5/Eldeen ranger 1), a clever gnome who hunts poachers and bandits.

Player’s Guide to Eberron

These are just a handful. There are surely other heroes and martyrs of both the Silver Crusade and the struggle for independence, as well as other guardian trees. And if you’re a shifter, there’s Olarune herself!

Were Eberron’s centaurs ever integrated into Galifar or the Five Nations?

So… In my Eberron, the large monstrosity centaur and medium fey centaur are entirely different creatures with completely different backgrounds and cultures, just as I suggested that fey changelings are entirely different from humanoid changelings. In my Eberron, there are a few different species of Monstrosity centaur, including one that’s more equine and one that’s more tribex (including bone headplates and short horns). With all of these subspecies, their humanoid torso has a distinct appearance ; they are half-humanoid, but you’d never mistake such a centaur for a human or elf; they are CENTAURS. By contrast, Fey centaurs vary dramatically in both aspects of their appearance; they aren’t limited to being equine, and their humanoid elements typically DO resemble another mortal species. So you may find a fey centaur that’s half-human, half-horse; but you could also find one that’s half-dwarf, half-riding dog or half-elf, half stag. These are primarily cosmetic details that don’t affect their statistics, and they aren’t limited by genetics but rather by story. Fey cenaturs are usually found near Thelanian manifest zones, and may have a consistent phenotype related to the story of that zone; but when they venture away and out into the wider world that becomes less fixed. Just as two shifters can have a child whose beast doesn’t match either of them, a human/horse fey centaur who mates with a dwarf/riding dog centaur could produce an elf/stag centaur.

Canonically, no, centaurs haven’t been significantly integrated into the Five Nations. The one place I know of where they are specifically called out in canon is the Player’s Guide to Eberron, which states that there are a few nomadic tribes of centaurs in the Eldeen Reaches, noting that they “are most common in the western forests near the Twilight Demesne.” Given that they are canonically denizens of the Towering Wood as opposed to the planes and in particular that they are associated with the Twilight Demesne—the largest Thelanian manifest zone presented in canon—I would say that the Eldeen centaurs are fey centaurs. I’d imagine that each nomadic tribe could have a different phenotype—there might be a tribe of elf/stags near the Demesne, a tribe of human/horses near the border between wood and field, a tribe of gnome/wolves in the north—though as noted above, fey centaurs don’t have to be consistent. In MY Eberron, the Wood centaurs are much like shifters: some tribes have chosen to completely ignore what’s going on in the east and follow their old traditions in the deep Wood, while others joined the Wardens of the Wood (or other sects—I can definitely imagine a centaur Greensinger) and have become part of the experiment. So definitely, in my campaign the Eldeen Reaches has a force of (fey) centaur cavalry as part of its military. With this in mind, I think that you could encounter Eldeen centaurs across the Five Nations just as you can encounter Greensingers or Wardens of the Wood across the Five Nations—they are rare and exotic, but not completely unknown.

But what about the NON-Fey centaurs? We’ve still never mentioned them as having a significant presence in the Five Nations and I’m not inclined to change that. I mentioned a strain of tribex centaurs and a strain of equine centaurs. In my campaign I have the tribex centaurs in the Talenta Plains and the equine centaurs in the Barrens of Droaam; in the Last War, it was actually Droaam that had a small force of centaur cavalry. Monstrosity centaurs can thus be encountered working with House Tharashk, but they are few in number and again, exotic and interesting.

Do you see the Voice of the Flame advising the Keeper of the Flame at the end of the Lycanthropic Purge to issue a public and formal apology to the shifters of the Eldeen Reaches?

tl;dr No, I don’t see the Church issuing a formal apology at the end of the Purge; but I can DEFINITELY imagine Jaela Daran issuing a formal apology today, perhaps even having an in-person ceremony in Greenheart.

Why the shift? First, it’s important to separate the Silver Crusade from the Lycanthropic Purge, as discussed in more detail in this article. The templars didn’t come to the region to kill shifters, they came to defend the innocent from lycanthropes. This started poorly, due to the fact that the raiding lycanthropes were almost entirely cursed shifters and that the wererats were actively working both to convince the templars that all shifters were the enemy and to convince the shifters that all templars were the enemy. But again, the shifters were also fighting the lycanthropes, and thanks to the work of heroes like Bennin Silverclaw, the two forces were able to work together as the conflict continued. There were ongoing tragedies throughout the Crusade, because that’s part of having a conflict with an enemy that can not only hide among your allies, but can turn your allies into your enemies with a bite. But again: shifters and templars were both fighting the lycanthropes, who posed an existential threat to ALL civilizations in the region. By the end of the conflict, templars were laying down their lives to protect shifter villages. Individual commanders surely apologized for tragedies they were involved in and may have done their best to make restitution in the moment. But overall, I don’t see the Church feeling that in needed to make a big public apology; countless templars had died fighting to protect both shifters and the people of Aundair.

… And then we get the Purge. But the thing about the Purge is that it wasn’t dictated by Flamekeep, and it wasn’t terribly well organized. It was an ongoing, slow, horrible persecution that lasted for decades. Most of all, it’s quite likely that the world at large—including Flamekeep—knew very little about it. This isn’t world with TV or internet. No one in Breland or Cyre had any awareness of what was going on the shifters in the Towering Wood. The Pure Flame templars surely reported to Flamekeep that they were engaging in absolutely necessary ongoing vigilance. Surely, over time, some word must have reached Flamekeep—I can imagine a heroic shifter making their way across Aundair to plead for help for their people. It’s possible the Keeper of the time did nothing, but it’s also possible they just didn’t do ENOUGH. They could have sent a strongly worded edict, they could have excommunicated a particular Pure Flame leader—meaning well but not understanding the extent of the hatred and the horror being committed. But not long after that, the Last War began… and I doubt apologizing to shifters was on anyone’s mind in the midst of the war.

Now the war is over. And now that the Eldeen Reaches are a nation, I’m sure that information about the horrors of the Purge are far more widely known. So NOW I see Jaela reaching out to make a formal apology for the Purge—for lighting the fire of the Pure Flame and leaving without foreseeing the danger, and for failing to do more to stop it. The mission of the Silver Flame is to protect all innocents; despite the noble intentions of the crusade, through its actions the Church set in motion a brutal tragedy that result in suffering and death for countless innocents. So yes, I think Jaela would apologize. And as I said, I could imagine a big public ceremony in the Greenheart—which could be a dramatic drive for adventures in many ways, especially if Jaela felt it necessary to attend in person, away from the power she wields in Flamekeep.

As a side note, I don’t see the Voice of the Flame as literally telling a Keeper what to do. Tira is more like an extremely strong conscience; she “speaks” more directly to a Keeper than to anyone else, but it’s still more about FEELINGS than her just say “Yo, Keeps! You fixed that shifter thing yet?” The Keeper can use commune to speak to Tira, but even then it’s up to the Keeper to set the topic. So if a Keeper said Should I do more to acknowledge the suffering of the shifters the Voice would say yes, absolutely—but she can’t force the topic if it doesn’t come up.

If the shifters of the Towering Wood are isolated tribes and may not even have had contact with the people of the fields… why do they speak Common? Shouldn’t they have their own language?

There’s a number of possible answers to this. As called out in this article, languages are one of the places where most settings sacrifice realism for ease of play—because it’s not a lot of FUN to have sessions where you go into the Reaches but get tripped up because no one speaks the Woodland language that no one uses anywhere else in Khorvaire.

With that in mind—it definitely doesn’t make sense that the Woodland shifters, as a whole, would speak Common. SOME would, because they’d have learned it as a trade language; I’m sure the Wardens of the Wood teach Common as part of the Eldeen experiment. So there’s nothing wrong with a player character shifter speaking Common even if they come from the deep Wood. But what would they actually speak at home?

- First of all, I WOULDN’T make the Deep Wood language Druidic. I’m of the opinion that Druidic is a magical language that can only be mastered by people who can work primal magic—that in some ways, the Druidic language is primal magic, but some rangers or initiates never master the whole thing. So there are definitely Moonspeakers who speak Druidic, but it’s not the language used by the Deep Wood shifters.

- Two valid possibilities are Orcish or Goblin. This would be strong evidence that the shifters are in fact descended from orcs. The question is if they’d speak Goblin because their ancestors adopted it during the Dhakaani reign—or would they have held onto Orcish, which would be someone amusing since we’ve suggested it’s a dead language even in the Shadow Marches?

- Another possibility would be that the Moonspeakers say Olarune taught them a language when they first mastered the Beast Within; this could be Sylvan or potentially Elven, if you use my ideas on Elven.

- If I were to say “They have their own entirely unique language that isn’t spoken anywhere else in Khorvaire” I would likely give this to any shifter player character from the region as a bonus language, without making them spend a language slot on it. From a practical standpoint, it’s a question of how often will the character actually use this? If the only time it will come up is when their cousin shows up in Sharn or on the two sessions the group makes a trip into the Wood, I’m fine with just giving it to a character as a bonus—just as I suggest that the Karrnathi native might be able to have a conversation with Karrn villagers the Thrane paladin can’t follow.

There’s some evidence that shifters are native to Sarlona as well given their presence in the Tashana Tundra. Did shifters independently arise in two places, or might there be a strange link between Tashana and the Reaches through Khyber?

My thought was the latter. With the timeline suggested, the emergence of shifters in the Wood would have still been thousands of years ago—easily enough time for a group of shifters to discover a land-bridge (well, demiplane bridge) through Khyber and for the common roots to have been forgotten. Given that those roots appear to have BEEN forgotten, the implication is that this bridge is either very infrequently active or that the passage leading to it has either been lost or claimed by a deadly force (hello, daelkyr) that severed any possible ties between the two cultures. There’s also been some discussion in the past of a remarkable sea crossing! The main point is that it’s been a long time—more than three thousand years—and there’s certainly been time for shifters to make it across the sea.

Is there any particular story to elves settling in the Wood?

Elves are present in the Eldeen Reaches, but there’s never been any mention of them having a unique, independent cultural identity. None of the sects are uniquely elvish and there’s no mention of entirely Elvish communities; instead, PGtE notes “the forest folk prefer to live in small mixed communities—human, elf, and shifter living side by side.” If you actually look at the numbers given in the ECS, elves make up a smaller percentage of the population of the Reaches than they do in ANY of the Five Nations; only 3% of the Reacher population are elves, compared to 11% of the population of Aundair! This may be because the elves were always based around the major cities of the east, or it could be that because of their long lifespans, most of the elves of the region remained loyal to Aundair and left the Reaches during the secession.

While the Reaches have fewer elves than any of the Five Nations, half-elves make up a considerable portion—16%, the same percentage seen in Aundair. The Player’s Guide to Eberron notes that fully half of the Greensingers in the Reaches are Khoravar. Combined with the statement that humans and elves live side by side, what this suggests to me is that a relatively small number of elves heard the call of the wild and immigrated to the Towering Wood over the years, but that they have very large families. So I think elves could be found in any of the druidic sects, and that where they are found they will often be elders with multiple generations of Khoravar children; there may only be a few established families of full-blooded elves. If one uses the subrace and considers eladrin to be elves, you could also have a handful of eladrin from Shae Loralyndar spread throughout the sects. Many would likely be Greensingers, still serving as envoys of their Queen. But you could easily have a few who have become attached to the mortal world and chosen to leave the City of Rose and Thorn.

So elves make up a small percentage of the population of the Reaches, and I feel that this would be split between the elves of the Wood—who would be spread across the sects, each with their own story about what drew them to the wild—and the elves of the fields, who were born as Aundairian citizens and chose to support the uprising even when most of their cousins chose not to.

One issue with the Reaches climatically is there’s no good way for the water from the Towering Wood to be replenished—the Wynarn river flowing north is going to drain water out of the system with Lake Galifar faster than any rain coming from the ocean (even off the Barren Sea) would naturally replenish it. Is there a Lamannia zone or some well of water from Khyber that’s kept things going?

Eberron is fundamentally a supernatural world; manifest zones and other mystical forces produce effects that defy what one would expect. This is especially notable with the Reaches, where just across the mountain you have the deeply unnatural and inhospitable environment of the Demon Wastes, while the Eldeen Reaches are said to be remarkably fertile. It’s certainly reasonable to think that there’s subterranean aquifers drawing water from Lamannia. It’s also possible that the region is simply infused with primal power—that it is close to Eberron herself. But the real issue here is that the maps simply don’t show a realistic distribution of waterways. I assume that there are streams and rivers flowing into the Towering Wood from both the Byeshk Mountains and the Shadowcrags, and that there are some significant bodies of water in the Wood (if nothing on the scale of Lake Galifar). Certainly, I’d expect the Icehorn Mountains to have considerable snowpack (perhaps enhanced by Risia) which would further contribute to the region.

That’s all for now! I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences with the Eldeen Reaches in the comments section, though I won’t be answering additional questions. Keep in mind that everything I write here is just what I would do in MY campaign and certainly contradicts some canon sources (I’m lookin’ at you, Forge of War). The idea that the shifters of the Towering Wood may be descended from orcs is a possibility, but not one you have to embrace. With that said, this ties to my general thought that half-orcs are a reflection of the remarkable adaptability of orcs rather than humans—that “half-orc” means orc and something else, not specifically orcs and humans. But that’s another story!

As always, thanks to my Patreon supporters for making these articles possible! As a bookend to March’s article on the Lurker in Shadow, later this month I’ll be writing a Patreon-exclusive article on the Wild Heart.

Unlock with Patreon

Unlock with Patreon