To view this content, you must be a member of Keith's Patreon at $5 or more

Already a qualifying Patreon member? Refresh to access this content.

“What do we do, Lightbearer?”

“We’ve got to hold this position,” Drego said. “We can’t let the wolves through the pass. But the people at the Crossroads need to know what we’ve learned about the thrice-damned rats.” He unpinned the raven brooch from his cloak, and whispered to it. Silver flame licked around the edges, and the metal melted and expanded, reforming into a bird with glittering feathers. After a few more words, the bird took to the air and disappeared into the canopy of the Towering Wood, heading south.

As time permits, I like to answer interesting questions posed by my Patreon supporters. Questions like…

A figurine of wondrous power is a magic item that can become a living creature for a particular duration or until the animal is killed. These are the mechanics, but it’s up to us to provide the flavor and the context. How common are they? Who makes them, and who uses them?

Starting with the first question, suggested rarity is a good place to start. What we’ve said before is that uncommon items can be found as part of everyday life in the Five Nations. Rare items are in fact rare; they exist, certainly, but aren’t part of everyday life. So it’s reasonable to think that a soldier in a special forces unit might be given a silver raven to help with communication, and one of Tharashk’s top bounty hunters might have an onyx dog to help with her hunts. But that onyx dog would be a remarkable tool… and the very rare obsidian steed would be almost unheard of in the Five Nations. Given both the material and the nature of the creature involved, I’d be likely to make obsidian steeds tools created by the Lords of Dust—perhaps by the Scribe Hektula, given to favored warlocks of Sul Khatesh.

So once again, figurines are mechanics. But there’s a lot of different ways that you could interpret those mechanics, based on the story you want to tell. So how do figurines fit into Eberron? I could imagine a few very different ways I’d use them.

The first figurines used by the people of the Five Nations were divine in nature, not arcane. Balinor is the Sovereign of Hunt and Hound, teaching people to work with beasts both as allies and as prey. Vassal figurines are engraved with Balinor’s symbol and imbued with faith. They function just like normal figurines, but they can only be recharged by devotion; such a figurine won’t regain its charge unless it’s in the possession of a devoted Vassal.

As noted in the quote that opens this article, the Church of the Silver Flame has also created such figurines. The most common of these is the silver raven, often used as a messenger by templars in the field; some of these take the form of small winged serpents, though they have no special abilities beyond flight. Like the Vassal figurines, these divine items can only be recharged by the faith of a follower of the Flame. I could also imagine Seekers of the Divinity Within crafting bone figurines of wondrous power; while one might expect such creatures to be skeletal, I’d be more inclined to make them vivid crimson beasts formed from the essence of the Seeker’s own blood.

Over the last century, House Cannith has been experimenting with figurines that replicate the basic principles of a creation forge. Cannith figurines can only be used by people who bear the Dragonmark of Making. They’re made of metal and wood, embedded with small siberys dragonshards. When activated, they grow bodies of root and steel, and have the Constructed Resilience trait of warforged. When the beast is killed or reverted, the materials that comprise it dissolve.

Both the Inspired and the kalashtar of Adar use figurines of wondrous power carved from sentira, a substance made from solidified emotion. The emotion used in the figure is reflected in the creature summoned; an onyx hound made from hatred will be cruel and aggressive, while one made from love will be gentle but protective of its summoner. The beasts summoned by sentira figurines have the statistics of the living creatures they resemble, but they’re formed from ectoplasm and often have dreamlike aspects—unnatural coloration, fur rippling in nonexistent wind, and a strong aura of the emotion that forms them. Activating a sentira figurine requires the user to feel the associated emotion intently; to use a figurine formed of hatred, the bearer will have to think of a creature they hate.

The elves of Aerenal—both Aereni and Tairnadal—create figurines of wondrous power. Both operate in a similar manner. When the figurine is activated, the translucent form of the summoned animal takes shape around the item. The summoned creature is solid and can be touched or ridden, and is in all ways treated as a living creature, but it is clearly ghostly and dissolves when its service is done. Aereni figurines are made using the spirits of beloved animals, while Tairnadal figurines are icons representing beasts of legend that fought alongside the patron ancestors. Both types of figurines are prized relics that typically have great emotional value to their owners, and are rarely sold; given this, Aereni or Tairnadal may be curious or angry if they see such items in the hands of others. Spectral figurines are often tied to the Valenar beasts presented in Eberron: Rising From The Last War; the equivalent of an onyx dog might summon a Valenar hound.

A number of the daelkyr have created Figurines of Wondrous Power. While functional, they’re not very pleasant…

These are just a few examples of possible figurines of wondrous power, and I’m sure you can come up with many more. As rare items most figurines would be, well, rare; I’d use the uncommon bag of tricks if I was creating a version of Pokemon in Eberron.

I won’t be answering questions on this IFAQ, but share your thoughts and ideas below. And if you’d like pose questions that could inspire future articles or participate in my online Eberron campaign, check out my Patreon!

House Tharashk is the youngest Dragonmarked house. The Mark of Finding first appeared a thousand years ago, and over the course of centuries the dragonmarked formed three powerful clans. It was these clans that worked with House Sivis, joining together in the model of the eastern houses. The name of the House—Tharashk—is an old Orc word that means united. Despite this, heirs of the house typically use their clan name rather than the house name. They may be united, but in daily life they remain ‘Aashta and Velderan.

The Dragonmarks are driven by more than simple genetics. In most dragonmarked houses, about half of the children develop some level of dragonmark. Over the course of a thousand years of excoriates and voluntary departures, many people in Khorvaire have some trace of dragonmarked blood. And yet, foundlings—people who develop a dragonmark outside a house—are so rare that many foundlings are surprised to learn that they have a connection to a house. Many houses allow outsiders to marry into their great lines, and the number of dragonmarked heirs born to such couples within the houses is dramatically higher than those born to excoriates outside of the houses. Scholars have proposed many theories to explain this discrepancy. Some say that it’s tied to proximity—that being around large numbers of dragonmarked people helps to nuture the latent mark within a child. Others say that it’s related to the tools and equipment used by the houses, that just being around a creation forge helps promote the development of the Mark of Making. One of the most interesting theories comes from the sage Ohnal Caldyn. A celebrated student of the Draconic Prophecy, Caldyn argued that the oft-invoked connection between dragonmarks and the Prophecy might be misunderstood—that rather than each dragonmarked individual having significance, the Prophecy might be more interested in dragonmarked families. It’s been over two thousand years since the Mark of Making appeared on the Vown and Juran lines of Cyre—and yet those families remain pillars of the house today.

This helps to explain the core structure of Tharashk, sometimes described as one, three, and many. There are many minor families within House Tharashk, but each of these is tied to one of the three great clans: Velderan, Torrn, and ‘Aashta. The house is based on the alliance between these three clans, and where most dragonmarked houses have a single matriarch or patriarch, Tharashk is governed by the Triumvirate, a body comprised of a leader from each of these clans.

When creating an adventurer or NPC from House Tharashk, you should decide which of the great clans they’re tied to. Each clan is tied to lesser families, so you’re not required to use one of these three names. A few lesser families are described here along with each clan, but you can make up lesser families. So you can be Jalo’uurga of House Tharashk; the question is which clan the ‘Uurga Tharashk are connected to. In theory, the loyalty of a Tharashk heir should be to house first, clan second, and family third. Heirs are expected to set aside family feuds and to focus on the greater picture, to pursue the rivalry between Deneith and Tharashk instead of sabotaging house efforts because of an old feud between ‘Uurga and Tulkar. But those feuds are never forgotten—and when it doesn’t threaten the interests of house or clan, heirs may be driven by these ancient rivalries.

To d’ or not to d’? Tharashk has never been bound by the traditions of the other houses, and this can be clearly seen in Tharashk names. Just look to the three Triumvirs of the house. All three possess dragonmarks, yet in the three of them we see three different conventions. Khandar’aashta doesn’t bother with the d’ prefix or use the house name. Daric d’Velderan uses his clan name, but appends the d’ as a nod to his dragonmark. Maagrim Torrn d’Tharashk uses the d’ but applies it to the house name; no one uses d’Torrn. Maagrim’s use of the house name makes a statement about her devotion to the alliance and the house. Daric’s use of the ‘d is a nod to the customs of the other houses. While Khandar makes no concessions to easterners. He may the one of the three leaders of House Tharashk, but he is Aashta. As an heir of House Tharashk, you could follow any of these styles, and you could change it over the course of your career as your attitude changes.

Orcs, Half-Orcs, and Humans. By canon, the Mark of Finding is the only dragonmark that appears on two ancestries—human and half-orc. However, by the current rules, the benefits of the Mark replace everything except age, size, and speed. Since humans and half-orcs have the same size and speed, functionally it makes very little difference which you are. It’s always been strange that this one mark bridges two species when the Khoravar marks don’t, and when orcs can’t develop it. As a result, in my campaign I say that any character with the Mark of Finding has orc blood in their veins. The choice of “human” or “half-orc” reflects how far removed you are from your orc ancestors and how obvious it is to people. But looking to the Triumvirs above, they’re ALL Jhorgun’taal; it’s simply that it’s less obvious with Daric d’Velderan. In my campaign I’d say that Daric has yellow irises, a slight point to his ears, and notable canine teeth; at a glance most would consider him to be human, but his dragonmark is proof that he’s Jhorgun’taal.

Characters and Lesser Clans. The entries that follow include suggestions for player characters from each clan and mention a few lesser clans associated with the major ones. These are only suggestions. If you want to play an evil orc barbarian from Clan Velderan, go ahead—and the lesser clans mentioned here are just a few examples.

The Azhani Language. Until relatively recently, the Marches were isolated from the rest of Khorvaire. The Goblin language took root during the Age of Monsters, but with the arrival of human refugees and the subsequent evolution of the blended culture, a new language evolved. Azhani is a blending of Goblin, Riedran, and a little of the long-dead Orc language. It’s close enough to Goblin that someone who speaks Goblin can understand Azhani, and vice-versa; however, nuances will be lost. For purposes of gameplay, one can list the language as Goblin (Azhani). More information about the Azhani language can be found in Don Bassinthwaite’s Dragon Below novels.

Before the rise of House Tharashk, most of the clans and tribes of the Shadow Marches lived in isolation, interacting only with their immediate neighbors. Velderan has always been the exception. The Velderan have long been renowned as fisherfolk and boatmen, driving barges and punts along the Glum River and the lesser waters of the Marches and trading with all of the clans. The clan is based in the coastal town of Urthhold, and for centuries they were the only clan that had any contact with the outside world. It was through this rare contact that reports of an unknown dragonmark made their way to House Sivis, and it was Velderan guides who took Sivis explorers into the Marches.

That spirit remains alive today. Where ‘Aashta and Torrn hold tightly to ancient—and fundamentally opposed—traditions, it’s the Velderan who dream of the future and embrace change, and their enthusiasm and charisma that often sways the others. Torrn and ‘Aashta are both devoted to the work of the house and the prosperity of their union, but it’s the Velderan who truly love meeting new people and spreading to new locations, and who are always searching for new tools and techniques. Stern ‘Aashta are always prepared to negotiate from a position of strength, but it’s the more flexible Velderan who most often serve as the diplomats of the house. While they work with House Lyrandar for long distance trade and transport, the Velderan also remain the primary river runners and guides within the Marches.

In the wider world, the Velderan are often encountered running enclaves in places where finesse and diplomacy are important. Beyond this, the Velderan are most devoted to the inquisitive services of the house; Velderan typically prefer unraveling mysteries to the more brutal work of bounty hunting. The Velderan have no strong ties to either the Gatekeepers or the “Old Ways” of Clan ‘Aashta; they are most interested in exploring new things, and are the most likely to adopt new faiths or traditions. Many outsiders conclude that the Velderan are largely human, and they do have a relatively small number of full orcs as compared to the other clans, but Jhorguun’taal are in the majority in Velderan; it’s just that most Velderan Jhorgun’taal are more human in appearance than the stereotype of the half-orc that’s common in the Five Nations.

Overall, the Velderan are the glue that holds Tharashk together. They’ve earned their reputation for optimism and idealism, and this is reflected by their Triumvir. However, there is a cabal of elders within the house—The Veldokaa—who are determined to maintain the union of Tharashk but to ensure that Velderan remains first among equals. Even while Velderan mediates between Torrn and ‘Aashta, the Veldokaa makes sure to keep their tensions alive so that they rarely ally against Velderan interests. Likewise, while it’s ‘Aashta who is most obvious in its ambition and aggression, it’s the Veldokaa who engage in more subtle sabotage of rivals. So Velderan wears a friendly face, and Daric d’Velderan is sincere in his altruism. But he’s not privy to all the plans of the Veldokaa, and there are other clan leaders—such as Khalar Velderan, who oversees Tharashk operations in Q’barra—who put ambition ahead of altruism.

Velderan Characters. With no strong ties to the Gatekeepers or the Dragon Below, Velderan adventurers are most often rangers, rogues, or even bards. Velderan are interested in the potential of arcane science, and can produce wizards or artificers. Overall, the Velderan are the most optimistic and altruistic of the Clans and the most likely to have good alignments—but an adventurer with ties to the Veldokaa could be tasked with secret work on behalf of the clan. Velderan most often speak Common, and are equally likely to speak Azhani Goblin or traditional Goblin.

Triumvir. Clan Velderan is currently represented by Daric d’Velderan. Daric embodies the altruistic spirit of his clan, and hopes to see Tharashk become a positive force in the world. His disarming humor and flexibility play a critical role in balancing the stronger tempers of Maagrim and Khandar. Daric wants to see the house expand, and is always searching for new opportunities and paths it can follow, but he isn’t as ruthless as Khandar’aashta and dislikes the growing tension between Tharashk and House Deneith. Daric is aware of the Veldokaa and knows that they support him as triumvir because his gentle nature hides their subtle agenda; he focuses on doing as much good as he can in the light while trusting his family to do what they must in the shadows.

Lesser Clans. The Orgaal are an orc-majority clan, and given this people often forget they’re allied with Velderan; as such, the Veldokaa often use them as spies and observers. The Torshaa are expert boatmen and are considered the most reliable guides in the Shadow Marches. The Vaalda are the finest hunters among the Velderan; it’s whispered that some among them train to hunt two-legged prey, and they produce Assassin rogues as well as hunters.

Torrn is the oldest of the Tharashk clans. The city of Valshar’ak has endured since days of Dhakaan, and holds a stone platform known as Vvaraak’s Throne. While true, fully initiated Gatekeepers are rare even within the Marches, the Torrn have long held to the broad traditions of the sect, opposing the Old Ways of ‘Aashta and its allies. Clan Torrn has the strongest traditions of primal magic within the Reaches, and ever since the union Torrn gleaners can be found providing vital services across the Marches; it was Torrn druids who raised the mighty murk oaks that serve as the primary supports of Zarash’ak. However, the clan isn’t mired in the past. The Torrn value tradition and are slow to change, but over the last five centuries they have studied the arcane science of the east and blended it with their primal traditions; there are magewrights among the Torrn as well as gleaners.

The Torrn are known for their stoicism and stability; a calm person could be described as being as patient as a Torrn. They refuse to act in haste, carefully studying all options and relying on wisdom rather than being driven by impulse or ambition. Of the three clans, they have the greatest respect for the natural world, but they also know how to make the most efficient use of its bounty. While ‘Aashta have always been known as the best hunters and Velderan loves the water, Torrn is closest to the earth. They are the finest prospectors of the Marches, and are usually found in charge of any major Tharashk mining operations, blending arcane science and dragonmarked tools with the primal magic of their ancestors. Most seek to minimize long-term damage to the environment, but there are Torrn overseers—especially those born outside the Marches—who are focused first and foremost on results, placing less weight on their druidic roots and embracing the economic ambitions of the house.

Most Torrn follow the basic principles of the Gatekeepers, which are not unlike the traditions of the Silver Flame—stand together, oppose supernatural evil, don’t traffic with aberrations. However, most apply these ideas to their own clan and to a wider degree, the united house. Torrn look out for Tharashk, but most aren’t concerned with protecting the world or fighting the daelkyr. Torrn miners may use sustainable methods in their mining, but they are driven by the desire for profit and to see their house prosper. However, there is a deep core of devoted Gatekeepers at the heart of Torrn. Known as the Valshar’ak Seal, they also seek to help Tharashk flourish as a house—because they wish to use its resources and every-increasing influence in the pursuit of their ancient mission. Again, most Torrn follow the broad traditions of the Gatekeepers, but only a devoted few know of the Valshar’ak Seal and its greater goals.

Within the world, the Torrn are most often associated with mining and prospecting, as well as construction and maintaining the general infrastructure of the house. The Torrn Jhorguun’taal typically resemble their orc ancestors, and it’s generally seen as the Clan with the greatest number of orcs.

Torrn Characters. Whether or not they’re tied to the Gatekeepers, Torrn has deep primal roots. Tharashk druids are almost always from Torrn, and Tharashk rangers have a strong primal focus; a Torrn Gatekeeper could also be an Oath of the Ancients paladin, with primal trappings instead of divine. The Torrn are stoic and hold to tradition, and tend toward neutral alignments. Most speak Azhani Goblin among themselves, though they learn Common as the language of trade.

Triumvir. Maagrim Torrn d’Tharashk represents the Torrn in the Triumvirate. The oldest Triumvir, she’s known for her wisdom and her patience, though she’s not afraid to shout down Khandar’aashta when he goes too far. Maagrim supports the Valshar’ak Seal, but as a Triumvir her primary focus is on the business and the success of the house; she helps channel resources to the Seal, but on a day to day basis she is most concerned with monitoring mining operations and maintaining infrastructure. She is firmly neutral, driven neither by cruelty or compassion; Maagrim does what must be done.

Lesser Clans. The Torruk are a small, orc-majority clan with strong ties to the Gatekeepers, known for fiercely hunting aberrations in the Reaches and for clashing with the ‘Aashta. The Brokaa are among the finest miners in the house and are increasingly more concerned with profits than with ancient traditions.

The ‘Aashta have long been known as the fiercest clan of the Shadow Marches. Their ancestral home, Patrahk’n, is on the eastern edge of the Shadow Marches and throughout history they’ve fought with worg packs from the Watching Wood, ogres and trolls, and even their own Gaa’aram cousins. Despite the bloody history, the ‘Aashta earned the respect of their neighbors, and over the last few centuries the ‘Aashta began to work with the people of what is now Droaam. The ‘Aashta thrive on conflict and the thrill of battle; they have always been the most enthusiastic bounty hunters, and during the Last War it was the ‘Aashta who devised the idea of the Dragonne’s Roar—brokering the service of monstrous mercenaries in the Five Nations, as well as the services of the ‘Aashta themselves.

The ‘Aashta are devoted to what they call the “Old Ways”—what scholars might identify as Cults of the Dragon Below. The two primary traditions within the ‘Aashta are the Inner Sun and the Whisperers, both of which are described in Exploring Eberron. Those who follow the Inner Sun seek to buy passage to a promised paradise with the blood of worthy enemies. The Whisperers are tied to the daelkyr Kyrzin; they’re best known for cultivating gibbering mouthers, but they have other traditions tied to the Bile Lord. The key point is that while the ‘Aashta are often technically cultists of the Dragon Below, they aren’t typically trying to free a daelkyr or an overlord. The ‘Aashta Inner Sun cultist is on a quest to find worthy enemies, to buy their own passage to paradise; they aren’t looking to collapse the world into chaos or anything like that. The Gatekeepers despise the cults for trafficking with malefic forces, and believe that they may be unwitting tools of evil, and it’s these beliefs that usually spark clashes between the two (combined with the fact that Gatekeeper champions are certainly ‘worthy foes’ in the eyes of the Inner Sun). But it’s important to recognize that these two paths have co-existed for thousands of years. That co-existence hasn’t always been peaceful, but they’ve never engaged in a total war. Since the union of Tharashk, both ‘Aashta and Torrn have done their best to work together, with Velderan helping to mediate between the two (… and with the Veldokaa occasionally stirring up the conflict).

The ‘Aashta are fierce and aggressive. They respect strength and courage, and take joy in competition. Having invested in the Tharashk union, they want to see the House rise to glory. It’s the ‘Aashta who pushed to create the Dragonne’s Roar despite the clear conflict with House Deneith. The ‘Aashta also recognize the power Tharashk has as the primary supplier of dragonshards, and wish to see how the house can use this influence. In contrast to the Veldokaa, the ‘Aashta are honest in their ambition and wish to see the house triumph as a whole. While they do produce a few inquisitives, their greatest love is bounty hunting, and most Tharashk hunters come from ‘Aashta or one of its allied clans.

While they aren’t as dedicated to innovation as Velderan and aren’t as invested in symbionts as the dwarf clans of Narathun or Soldorak in the Mror Holds, the ‘Aashta are always searching for new weapons and don’t care if a tool frightens others. Some of those who follow the Old Ways master the techniques of the warlock, while the Whisperers employ strange molds and symbionts tied to Kyrzin and produce gifted alchemists.

‘Aashta Characters. The ‘Aashta are extremely aggressive. While there are disciplined fighters among them—often working with the Dragonne’s Roar to train and lead mercenary troops—the ‘Aashta are also known for cunning rangers and fierce barbarians. Their devotion to the Old Ways can produce warlocks or sorcerers, and especially gifted Whisperers can become Alchemist artificers. Culturally, the ‘Aashta are the most ruthless of the clans and this can lead to characters with evil alignments, though this is driven more by a lack of mercy than by wanton cruelty; like followers of the Mockery, an ‘Aashta will do whatever it takes to achieve victory. Due to its proximity to Droaam, the people of Patrahk’n speak traditional Goblin rather than Azhani, as well as learning Common as a trade language; however, ‘Aashta from the west may prefer Azhani.

Triumvir. Khandar’aashta is bold and charismatic. He is extremely ambitious and is constantly pushing his fellow Triumvirs, seeking to expand the power of Tharashk even if it strains their relations with the rest of the Twelve. Khandar is a follower of the Old Ways; it’s up to the DM to decide if he’s a Whisperer, pursuing the Inner Sun, or if he’s tied to a different and more sinister tradition. While he is ruthless when it comes to expanding the power of the house, he does believe in the union and wants to see all the clans prosper.

Lesser Clans. Overall, the ‘Aashta have no great love of subterfuge. When they need such schemes, they turn to the ‘Arrna, a lesser clan who produces more rogues than rangers. While they are just as aggressive as the ‘Aashta, the ‘Aarna love intrigues and fighting with words as well as blades. The Istaaran are devoted Whisperers and skilled alchemists; they have a great love of poisons and have helped to produce nonlethal toxins to help bounty hunters bring down their prey. The ‘Oorac are a small clan known for producing aberrant dragonmarks and sorcerers; before the union they were often persecuted, but ‘Aashta shields them.

That’s all for now. I’m pressed for time and likely won’t be able to answer questions on this topic. Meanwhile, if you’re interested in shaping the topic of the NEXT article, there’s just four hours left (as of this posting) in the Patreon poll to choose it; at the moment it’s neck and neck between an exploration of Sky Piracy in Khorvaire and my suggestions for drawing players into the world and developing interesting Eberron characters in Session Zero. In addition, tomorrow I’ll be posting the challenge that will determine which Threshold patrons play in my next online adventure. If you want to be a part of any of that, check out my Patreon!

As time permits, I like to answer interesting questions posed by my Patreon supporters. This month, a number of questions circled around the same topic—how would I integrate gem dragons and gem dragonborn into my Eberron? In adding anything new to the setting, by question is always how it makes the story more interesting. I don’t want to just drop gem dragons into Argonnessen and say they’ve always been there; I want them to change the story in an interesting way, to surprise players or give them something new to think about. So here’s what I would do.

Eberron as we know it isn’t the first incarnation of the prime material plane. We don’t know how many times reality has fundamentally shifted, jumping to a new rat in the maze of reality. But we know of one previous incarnation because of its survivors. When their reality was on the brink of destruction, a rag-tag fleet of Gith vessels escaped into the astral plane. These survivors split into two cultures, with the Githzerai dwelling in vast monasteries in Kythri and the Githyanki mooring their city-ships in the astral plane. The transition of realities is a difficult thing to map to time. For us, our reality has always existed, going back to the dawn of creation. For the Gith, the loss of their world is still a thing some hold in living memory. They are hardened survivors. Some crave revenge on the daelkyr, while others are solely concerned with the survival of their people. But the Githyanki aren’t the only survivors of their reality. It was an amethyst greatwyrm who helped the Gith fleet break the walls of space, and a small host of dragons accompanied the survivors into their astral exile. But the dragons aren’t like the metallic and chromatic dragons of the world that we know. They are the gem dragons.

The Progenitors are constants across all versions of the material plane. They created the planar structure of reality, and the material plane is the end result of their labors. The Eberron of the Gith—let’s call it “Githberron”—started with the same primordial struggle. In the current Eberron, the dragons are said to have formed when Siberys’s blood fell onto Eberron. In Githberron, Khyber didn’t tear apart Siberys’s body; she shattered his mind. The gem dragons believed that fragments of Siberys’s consciousness were scattered through reality, and they sought to reunite these shards; just as arcane magic is said to be the blood of Siberys in Eberron, in Githberron psionic energy is called the dream of Siberys.

Where the dragons of our Eberron are concentrated in Argonnessen, the dragons of Githberron were spread across their world. However, they were culturally connected through a telepathic construct—a vast metaconcert, which they believed was a step toward reuniting the shattered Siberys. They called this psychic nation Sardior. So rather than Sardior being another Progenitor, Sardior was their answer to Argonnessen—and they believe it is the soul of Siberys. This idea involves a small but crucial chance to the gem stat block, which is that I’d add Trance (as the elf racial trait) to all gem dragons. When trancing, gem dragons would project their consciousness into Sardior. Today the survivors yearn to recreate Sardior, and each gem dragon carries their own piece of it within their mind; however, I’m inclined to say that there just aren’t enough of them to sustain a global (let alone extraplanar) metaconcert. Two gem dragons in the same place might be able to link their minds when they trance, to dwell together in a sliver of Sardior. But to truly restore the dream of Siberys, they need more dragons. But there’s a catch to that…

In modern Eberron, dragons reproduce as other creatures do. My gem dragons of Sardior, on the other hand, use one of the other methods described in Fizban’s Treasury of Dragons:

Enlightened non-dragons (most often Humanoids) are transformed into dragon eggs when they die, when they experience profound enlightenment… Humanoids and dragons alike understand the transformation to be a transition into a higher state of existence.

The gem dragons of Sardior weren’t born in isolation; they are the evolved, transcendent forms of other denizens of Githberron. This means that they have a fundamentally different relationship with humanoids than the dragons of Argonnessen. In the current Eberron, dragons see humanoids much like mice; useful for experiments, but don’t feel bad if you have to exterminate them, and isn’t it cute when they think they’re dragons. By contrast, in the Gith Eberron, dragons all evolved from humanoids, meaning both that they have memories of their humanoid existence and that they rely on humanoids to propagate their species. This is one of the key reasons they work with the Gith, even if they don’t especially like the Githyanki raiding. Not only are the Gith the last survivors of their world, they may be the only species capable of producing new gem dragons.

So, what is this process of reproduction and enlightenment? First, it requires a certain degree of psionic aptitude. The dragons see psionic energy as the dream of Siberys, and to become a dragon you are essentially drawing the essence of Siberys into yourself; what it means to be a dragon is to become a refined shard of the mind of Siberys. This doesn’t requires all pre-dragons to be full psions, but you need to have some degree of psionic ability, even if it’s just one of the psionic feats from Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything. The second aspect is more ineffable, and it involves unlocking your full potential—becoming the best version of yourself that you can be. In many ways this is similar to the idea of mastering the Divinity Within in the Blood of Vol, or becoming worthy of Ascension to the Undying Court in Aerenal, and it should be just as difficult; it’s usually the work of a lifetime, not something you can rush. And I’d combine the two aspects of the Fizban’s quote—the ascension requires both enlightenment and death, that on death you become a gem dragon egg. So the point is, become enlightened, live your enlightened life, and hope that when you die you’re reborn as a dragon—you don’t want to rush the process unless you’re really sure you’re sufficiently enlightened. It’s definitely something that could happen to a player character, but it would only happen when they die.

A second key aspect of this is the idea that the type of dragon you become reflects the path you walked in life. The reason sapphire dragons are warlike is because they were warriors in their first lives. Amethyst dragons were planar scholars devoted to fighting aberrations before they became dragons; if a Gatekeeper from Eberron became a gem dragon, they’d be amethyst. I’m inclined to say that some of the character’s original memories and skills are lost in the process of draconic ascension, since it would be a significant change to say that every gem wyrmling has the skills of a mortal paragon—but the essence of that first life remains and guides the dragon moving forward. While the wyrmling may not have the full skills of the mortal seed, they have its wisdom and determination, the experience of a life well lived.

In my campaign, there are less than a hundred dragons of Sardior in the current reality. They have a single greatwyrm—an amethyst dragon who played a crucual role in helping the Gith escape their doomed reality and who generally resides at and protects Tu’narath in the astral plane. But again, each gem dragons—even the Wyrmlings—has a rich story of a prior life. Some were Gith warriors who fought against the daelkyr. Some were sages or scholars. In building an encounter with a gem dragon, the first question for the DM should be who were they before they became a dragon?

Gem dragons work with the Gith—both Githzerai and Githyanki—for many reasons. Many of the dragons were Gith before their ascension (though there were many other humanoid species on their world) and they are the last remnant of their lost world. Beyond that, the dragons yearn to recreate Sardior, and the dragons don’t yet know if it’s possible for humanoids of this reality to undergo draconic ascension; the Gith may be the only source of new gem dragons. The dragons who join Githyanki on their raids are primarily sapphire dragons, many of whom were Gith warriors in their former lives and who want to keep their people sharp; amethyst dragons are typically found in the monasteries of the Githzerai, helping build their dream of striking at Xoriat. But not all gem dragons work with the Gith. Here’s a number of ways that adventurers could encounter a gem dragon in my Eberron.

While most of these paths are largely benevolent, there’s certainly room for any of these dragons to go down a sinister path. A guardian may place the survival of the Gith above all else, caring nothing for the damage they do to this cracked mirror in pursuit of their goals. A mentor could eliminate students who fail to live up to expectations—or kill them believing that they will become dragon eggs, only to discover that they weren’t ready.

A key question is how Argonnessen interacts with gem dragons, and whether gem dragons are vulnerable to the influence of the Daughter of Khyber. Given that they are from an alien reality and are so different in how they are formed, I am inclined to say both that gem dragons aren’t affected by the Daughter of Khyber and also that they don’t show up in the Draconic Prophecy. With this in mind, in my campaign, Argonnessen doesn’t know much about gem dragons. Because they can and have spontaneously manifested over the course of history, Argonnessen dismisses isolated encounters with gem dragons as fluke occurrences, thinking they’re much like a draconic version of tieflings or aasimar; they haven’t yet realized that there is a civilization of gem dragons active in the world. This gives player characters the opportunity to have a front row seat for the full first and open contact between Sardior and Argonnessen. The Sardior dragons have been studying Argonnessen via their draconic observers and dealing with a few individual sympathetic dragons, but they haven’t yet dealt with the Conclave or the Chamber—and adventurers could be a part of this event when it occurs. Will the Conclave work with these alien dragons? Or will they view them as a threat that should be eliminated? A second plot thread I might explore is the idea that the gem dragons aren’t as vulnerable to the Daughter of Khyber as native dragons, but that they aren’t immune to her influence… that a gem dragon who remains on Eberron and exercises its power might slowly be corrupted by the overlord, turning a valued ally into an enemy. The main point is that I’d rather have these things occur as part of the story the player characters are involved in than to be something that occurred long ago.

One important question is how the dragons of Sardior interact with the psi-active forces of the current Eberron, notably Adarans, kalashtar, and the Dreaming Dark. If psionic talent is a cornerstone of the evolution into a gem dragon the kalashtar could be natural allies for Sardior; the Adaran shroud would also make Adar a compelling place to have a secure Gith creche for raising children. On the other hand, it’s possible that because kalashtar psionic talent is tied to an alien spirit that the kalashtar are a spiritual dead end or at least would have MORE trouble ascending than other humanoids. It could be that Adar is already home to one or more native gem dragons; it could be very interesting to reveal that there’s always been a gem greatwyrm hidden beneath Adar, helping to protect its people.

On the other side of things, gem dragons might be more interested in Riedra and the Inspired. Could the Hanbalani be hijacked to create a form of Sardior? On the other hand, once the gem dragons have revealed their presence, I could imagine the Dreaming Dark trying to capture and use them; this could be the source of an obsidian dragon.

The main point to me is that I’m always more interested in having interesting things happen NOW than setting them in the past. I’d rather have Adaran or Kalashtar players be actively involved when a Sardior emissary comes to Adar and asks to build a creche than to say that it happened a century ago… though I do love the idea of the revelation that there have always been a few native gem dragons in Adar who have helped to guide and protect the nation!

In my Eberron, gem dragonborn are like gem dragons, in that they aren’t a species that reproduces with others of their kind; they must be created. For these purposes, I’d consider the half-dragon origins suggested in Fizban’s Treasury of Dragons. True Love’s Gift suggests that a bond of love between a dragon and another creature can produce a dragonborn, while Cradle Favor suggests that some gem dragons can transform an unborn child. How and why this could occur would depend on the nature of the dragon sharing their power. A guardian dragon could cultivate a squad of dragonborn soldiers. Likewise, a mentor could cultivate a small family of dragonborn to help with its mission. On the other hand, a secretive hedonist or mentor could produce a dragonborn through a bond of love, with the child and their mother never knowing the true nature of the draconic godparent. On the other hand, Fizban’s offers other possible paths to becoming a half-dragon… notably, the idea that “A creature that bathes in or drinks the blood of a dragon can sometimes be transformed into a half-dragon.” I wouldn’t make this reliable or easy technique… but it leaves the possibility that some of the Draleus Tairn hunt gem dragons for this reason, or that a dying gem dragon might choose to give the last power of its blood to a humanoid that finds it.

This provides a range of options for a gem dragonborn player character. If you’re tied to a guardian, it means that you have an active connection to the Sardior survivors and a Gith vessel. Why have you left your ship? Have you been exiled for some crime, and seek to clear your name? Do you have a specific mission, whether diplomatic or searching for a particular artifact? If you’re tied to a mentor, you could have a relationship with your draconic benefactor not unlike that of a warlock and their patron; your dragon seeks to gather information and to help elevate humaniodity, and you are their eyes and hands. On the other hand, it could be that you were born as a gem dragonborn but don’t know why—that part of your quest is to discover the dragon who transformed you and to learn why.

Given my theory of Githberron, one might ask what this means for Gith player characters. Are all Githyanki survivors of Githberron? Do all Gith have to have a connection to the Astral or to Kythri? A few thoughts…

The timeless nature of the astral plane means that you could play a Githyanki character who’s a survivor of the lost world. Part of the idea of Githberron/Sardior is that psionic energy was more abundant there, so you could justify being a low-level character by saying that you were a more powerful psion in your own world and part of the reason you’re traveling is to learn to work with the lesser energies of this one. With that said, the Githyanki do want to continue to grow their population; in this article I suggest the existence of creche ships that serve this purpose. I imagine adolescent Githyanki having a sort of rumspringa period—they have to be out of the astral until they physically mature, and some ships might encourage their youths to explore the material plane in this time, learning about the wider world, honing their skills, and making potential allies. Meanwhile, Kythri ISN’T timeless—which among other things suggests that the only Githzerai who personally remember Githberron are monks who’ve mastered some form of the Timeless Body technique (which I’d personally allow some Githzerai NPCs to do even if they don’t have all the other powers of a 15th level monk). On the other hand, because we are dealing with events that defy the concept of linear time, if it suits the story a DM could decide that from the perspective of the Gith, it’s only actually been a few decades since Githberron was lost! Either way, I could also see the Githzerai having a wandering period where their adolescents experience life in the material plane, to understand existence beyond Kythri.

In any case, I would say that all Gith have a connection to either a city-ship or a monastery. So as a Gith, why might you be an adventurer? A few ideas…

That’s all for now! I don’t have time to answer many questions on this article, but feel free to discuss your ideas and ways you’ve used gem dragons or Gith in the comments. If you want to see more of these articles, to have a chance to choose future topics, or to play in my ongoing online Eberron campaign, check out my Patreon!

Every month I answer interesting questions posed by my Patreon supporters. Here’s a few more from April!

First of all, what’s the nation? If it’s Aundair, is there something interesting going on with everyday magic or fey? If it’s Thrane, how does the faith in the Silver Flame manifest? If it’s Karrnath, is it more influenced by Seekers or by Karrnath’s martial traditions? Can you feel the weight of the Code of Kaius? If it’s Breland, is there crime? Do they support the monarchy or the Swords of Liberty? Outside the Five Nations, is there a manifest zone? Is it tied to a daelkyr or an overlord? Is there an interesting resource or an unusual creature?

Another thing to consider is the stories people tell. For example, in Frontiers of Eberron I dealt with Whitehorn Woods for the first time, which raised the question “Why do people call it Whitehorn Wood?” So, I decided that the people in the region tell stories of Whitehorn, a massive horned bear. Essentially, if a place has a name, there’s surely a reason for the name—what’s a logical explanation you can come up with?

Beyond that, I will often ask my players to help flesh these things out. If I was running a game tomorrow in the Whitehorn Woods, I’d start by telling people about the bear, and then I’d ask each player “Tell me something you’ve heard about the Whitehorn Woods.” I did this in Threshold just recently, when I asked players to tell me something they’d heard about the Byeshk Mine. I didn’t USE all those answers—not every story has to be true—but it was a useful source of inspiration.

There’s two important things to consider here. The first is that the Sovereigns appear in many different cultures and with many different variations. Clearly Banor of the Bloody Spear, Bally-Nur, and the Pyrinean Balinor won’t all look the same; one’s a giant, one’s a halfling, one isn’t locked into any one species. Even within the Five Nations, you have many subsects within the broad Pyrinean tradition—the Church of the Wyrm Ascendant, the Restful Watch, Aureon’s Word, the Order of the Broken Blade, the Three Faces, and so on.

The second important point is that on some level, the exact appearance of the Sovereigns doesn’t matter, because the idea of the Sovereigns is that they aren’t going to appear and interact with you physically, but rather that they are with you at all times, offering guidance.

Is there art depicting the myths of the Sovereigns? Absolutely. But the key is that there’s no absolute agreement on what they look like, so instead what’s crucial is symbols. The first of these is called out in the original ECS: Dragons. Each of the Sovereigns is associated with a particular dragon; the blue dragon is a symbol of Aureon, while the silver dragon is used to represent Dol Dorn. Beyond this, each Sovereign has a particular iconic symbol, suggested in Faiths of Eberron; Aureon can be recognized by his book, while Arawai holds a sheaf of wheat. The ECS also assigns a favored weapon to each Sovereign, but I didn’t choose these and I strongly disagree with some of the choices. As Sovereign of the fields, it would make sense for Arawai to be associated with a farming implement, such as the flail or the scythe; instead, she’s canonically tied to the morningstar (which is sometimes depicted as a ball-and-chain, but definitely not a farming implement). Balinor is the Sovereign of the Hunt but is canonically tied to the battleaxe, hardly a traditional choice for a hunter. With that in mind, I’ll suggest kanonical alternatives befow.

With all this in mind, the point is that artwork depicting the Sovereigns focuses on SYMBOLS. There’s no one universally accepted depiction of Dol Dorn, but he’s always muscular and carries a longsword, often crossed over a shield. Dol Arrah holds her halberd with the sun rising behind her; if that doesn’t fit in the image, she’ll have a rising sun worked into her clothing. The humanoid models vary by sect and region, and often use historical or living figures considered to exemplify that Sovereign’s traits. For example, there may be a church in Sharn with a mural that depicts war heroes Khandan the Hammer as Dol Dorn (wielding a longsword instead of his famous hammer) and Meira the Huntress as Balinor. If you’re Brelish, you know Khandan as a warrior renowned for his strength and courage, and this combined with his pose, his obvious strength, and his sword and shield make it clear he’s representing Dol Dorn; if they really wanted to lay it on, they could add a silver dragon in a pennant or a brooch. Meanwhile, Meira the Huntress would be recognized as Balinor by her bow, by the antlers mounted on her helm, and by the fact that she’s clearly a huntress. It doesn’t matter that Balinor is considered to be male, because what this picture is truly depicting is Balinor acting through Meira—because THAT is how you’ll actually encounter the Sovereigns in the world. In using real people as models for the Sovereigns, these images remind us that the Sovereigns are with us all.

| Sovereign | Dragon | Weapon | Symbol |

| Arawai | Bronze | Flail | Sheaf of Wheat |

| Aureon | Blue | Quarterstaff | Book |

| Balinor | Green | Bow | Antlers |

| Boldrei | Copper | Spear | Hearth |

| Dol Arrah | Red | Halberd | Rising Sun |

| Dol Dorn | Silver | Longsword | Shield |

| Kol Korran | White | Mace | Gold Coin |

| Olladra | Black | Dagger | Domino or Dice |

| Onatar | Brass | Warhammer | Hammer and Tongs |

I’ve never used the Nagpa. As I understand the story, the idea is that they’re mortal wizards who were cursed by the Raven Queen for meddling in a war between gods. Now they plot in the shadows, but presumably on a smaller scale than, for example, the Lords of Dust; they are still cursed mortals.

The first thing I’d do is to drop the Raven Queen and evaluate the core overall story. Mortals meddle, are cursed by a wrathful being of deific power. Playing to the idea that they “interfered in a war between gods” the most obvious answer to me is that they weren’t HUMAN wizards… they were DRAGONS. They interfered in the first war—the conflict between dragon and overlord—and were cursed by Ourelonastrix, forever bound to these pathetic, humanoid forms. Powerful as they are, they’re still feeble next to the glory of a greatwyrm, and you can see how their state would be a considerable humiliation. With this in mind, they can then have been present in EVERY disaster that’s come since. They could have played a key role in Aureon’s Folly; perhaps it was one of the Nagpa who urged the giants to use the Moonbreaker. Rival Nagpa could have helped different mazes in Ohr Kaluun, or Khunan. A key point would be that unlike the Chamber or the Lords of Dust, the Nagpa aren’t driven by the Prophecy and don’t know what the long-term impact of their actions—they just enjoy sowing chaos and causing trouble for all sides. If I didn’t want to do that, the next approach that comes to mind is to make them cursed acolytes of Sul Khatesh, twisted by their devotion to the Queen of Shadows—cursed with ugly immortality until they can unlock some particular arcane mystery. This could be tied to her release—making them allies of Hektula and an adjunct of the Lords of Dust—or they could just be an entirely separate faction which, again, has no knowledge of the Prophecy and are purely devoted to pursuing their own selfish problem. Another option would be to work with Thelanis, as the whole “cursed wizard” story sounds very Thelanian. But personally, I’d either go with cursed dragons or ancient Khorvairians.

A few years back, my friend Dan Garrison—the co-designer of Phoenix: Dawn Command—ran an Eberron campaign called “The Fall of Cyre”. It began in Metrol on the eve of the Day of Mourning, at the celebration of Princess Marhya’s betrothal. That was the night we danced the Tago with knives! Marhya was the younger sister of Oargev, which in my current view would make her a granddaughter of Dannel. My character in that campaign was the warforged envoy Rose, who was built to serve as a companion to the Princess; Rose is depicted in Exploring Eberron and mentioned in the article on Oargev’s suitors.

In Dan’s campaign, Marhya was betrothed to Prince Jurian of Aundair… though of course, this isn’t canon. Marhya was competent, trained in statecraft and with the sword, determined to do what she could to ensure peace and safety for her people. In that campaign, Metrol was also sucked into Mabar, but more in the typical Hinterlands way—so apocalyptic chaos rather than the dystopia of Dread Metrol. Marhya was the natural leader who needed to unite the survivors and find a way out of the nightmare. Good times!

As with most IFAQs, I won’t be expanding further on these topics, but feel free to discuss them in the comments! If you have questions of you’re own, I’ll be posting a new call for questions for my Patreon supporters soon!

As time allows, I like to answer interesting questions posed by my Patreon supporters. Here’s two from this month!

“You aren’t in your Five Nations any more,” Sheshka said. She had sheathed her sword, but her voice was deadly. “You have come to my home. Your soldier threatened me with a blindfold. A blindfold, on my soil. Would I come into your castle and strip away your sword, or demand that you wear chains?”

“We can’t kill with a glance,” Beren said.

“And that excuses your threat to pluck out my eyes? Should I cut off your hands so you cannot strangle me?” The medusa’s eyelids fluttered, but remained closed. “Hand, tooth, steel – we are all deadly.”

The Queen of Stone

Canonically, while in the cities of the Five Nations a medusa is expected to wear eyeblinders, described as a metal visor that straps around the forehead and chin and takes multiple rounds to remove; in especially high-security situations, the straps can be secured with a lock. Of course, this varies by location; in a small village in Karrnath the sheriff surely doesn’t have a set of eyeblinders lying around, and in Callestan in Sharn, who exactly is going to demand the medusa put on eyeblinders? In such situations, a medusa will often wear a veil or more comfortable blindfold, as Tashka is modeling in the image accompanying this article. Such a blindfold doesn’t offer as much security as a set of eyeblinders, since it could be removed in a single action, but it’s a compromise; you don’t have to worry unless I take it off.

With this in mind, have blindfolds become part of standard medusa fashion? Do medusas wear blindfolds in Graywall or the Great Crag, or even in Cazhaak Draal? Definitely not. Medusas are perfectly capable of controlling their deadly gaze. Let’s start with simple mechanics. Here’s the 5E interpretation of the ability in question.

Petrifying Gaze. When a creature that can see the medusa’s eyes starts its turn within 30 feet of the medusa, the medusa can force it to make a DC 14 Constitution saving throw if the medusa isn’t incapacitated and can see the creature.

I’ve bolded the key word there—they can force someone to make a saving throw, but they don’t have to. While some people may interpret this as meaning that the medusa can choose to look you straight in the eye and not petrify you, how I interpret it in my campaign is that the medusa can never turn off their power, but that they have to look you directly in the eye to make it work and they’re very good at avoiding such accidental eye contact… and if they really want to play it safe, they can just close their eyes. This is something discussed in a canonical Dragonshard article…

The gaze of a medusa can petrify even an ally, and as a result, a medusa does not meet the gaze of a person with whom it is conversing. Where she directs her eyes indicates her esteem for the person. She drops her eyes toward the ground to show respect, or looks up and over the person if she wishes to indicate disdain; when speaking to an equal, she glances to the left or right. If she wishes to show trust, she directs her gaze to the person, but closes her eyes.

While this may seem inconvenient to a human, it has little impact on a medusa. If a medusa concentrates, she can receive limited visual impressions from the serpents that make up her hair; as a result, though she seems to look elsewhere, she’s actually looking through the eyes of her serpents. She can even use her serpents to see when she is blindfolded or has her eyes closed. However, she can still “see” in only one direction in this way; her serpents may look all around her, but she can’t process the information from all of them at once.

While I like the idea of looking up or down to signal respect when dealing with an individual, things get a little trickier on a crowded city street where accidental eye contact could easily happen—but in such a situation, again, all the medusa has to do is to close their eyes. To me, this is the absolute reason a medusa can’t petrify you by accident, and why you only have to make that saving throw if they choose to force you to; if they don’t want to hurt you, they’ll close their eyes.

So, with this in mind, no, medusas don’t wearing eyeblinders when they’re at home. The power of the medusa is a gift of the Shadow and they are proud of this gift; it’s not their job to calm your fears. And as Sheshka points out, everyone is dangerous, especially in Droaam; no one expects gargoyles to file down their claws, or Xorchylic to bind his tentacles. Demanding that a medusa cover their eyes is demeaning and shows a lack of trust. They’ll put up with it when the local laws require it, though even then they may skirt it (as with Tashka wearing a blindfold instead of full eyeblinders). But they certainly aren’t going to wear a blindfold while at home just to make you more comfortable.

First of all, we need to address the tribex in the room, and that is that population numbers in Eberron have never been realistic. In part this is because we’ve never entirely agreed on the scale of the map; there’s also the broader question of whether population numbers should reflect medieval traditions (as was typical for D&D at the time the ECS was released) or if, given that society’s advances are more like late 19th century Earth, the population should reflect that as well. Consider that in 1900, London was home to five million people… while in the 3.5 Eberron Campaign Setting, Breland only has a total population of 3.7 million.

For this reason, the 3.5 ECS is the only book that actually gives population numbers for the nations; neither the 4E ECG or 5E’s Rising From The Last War do. Because at the end of the day, the exact number usually isn’t important. What matters is that we know that Aundair has the lowest population of the Five Nations and that Breland has the highest. It’s good to know that Sharn is the largest city in the Five Nations, even if I’d personally magnify its listed population by a factor of five or more. So I DO use the numbers given in the Eberron Campaign Setting, but what I use are the demographics break-downs—for example, the idea that dwarves make up a significant portion of the population of Breland, but are relatively rare in Aundair—while I use the population numbers just as a way of comparing one nation to another, so I know the population of Breland is almost twice that of Aundair.

So: I use the stats of the ECS, but I use them for purposes of comparing one nation to another, not for purposes of setting an absolute number. With that in mind, let’s look back to the original question: Is it strange that humans only make up 6% of the population of Darguun? In my opinion, not at all. The key is to understand the difference between the Darguun uprising and the Last War as a whole. During the Last War, the Five Nations were fighting over who was the rightful heir to the throne of Galifar. As discussed in this article, the goal—at least at the start—was reunification, and the question was who would be in charge. It was never a total war; the Five Nations agreed on the rules of war and whenever possible, avoided targeting civilian populations or critical civic infrastructure.

None of this applied to the Darguun uprising. The ECS observes that “Over the course of the Last War, most of the towns, temples, and fortresses in the region were razed and abandoned.” Not conquered and occupied: razed and abandoned. The Darguuls didn’t have the numbers to rule as occupiers, so they DESTROYED what they couldn’t control, driving the people away or killing them. It was an intensely brutal, ugly conflict, driven both by history—in the eyes of the Darguuls, the people of Cyre were the chaat’oor who had stolen the land and brutalized their ancestors—and by the fact that it needed to be swift and brutal, to maximize the impact before the Cyrans could regroup. By the time central Cyre was truly aware of the situation in southern Cyre, there was nothing left to save.

So I think the the demographic percentages are reasonable; I think most of that human 6% have actually come to Darguun after the war to do business or as expatriates of other nations. This ties to the point that Darguun is a nation of ruins—again, as the ECS says, “most of the towns, temples, and fortresses were razed and abandoned.” In my Eberron, the population of Darguun is far lower today than it was before the uprising; again, part of the reason for the brutality was because they didn’t have the numbers to rule through occupation. Darguuls are slowly reclaiming ruined towns and cities, building their own towns on the foundations just as humanity built many of its greatest cities on Dhakaani foundations—but overall, much of Darguun is filled with abandoned ruins that have yet to be reclaimed.

This brings up another important point. I agree with the demographic percentages of the ECS, but I think the listed population of Darguun is too high. Darguun is listed as having a population of 800,000. Again, I’m not concerned with that actual number—I’m concerned with how it compares to other nations. At 800,000, Darguun is the size of the Lhazaar Principalities, Zilargo, and Valenar combined. The whole idea of Darguun is that a relatively small force laid waste to the region because they lacked the numbers to conquer it. Now, in my Eberron the goblin population has swelled since the uprising. Haruuc’s people—the Ghaal’dar—were based in the Seawall Mountains and the lands around it. The dar were scattered and living in caverns, peaks, deep woods. As word spread of a goblin nation, tribes and clans came to Darguun from elsewhere in Khorvaire—from deeper in Zilargo, from Valenar, from central Cyre. This ties to the reasons Haruuc often has difficulty exercising control. The Ghaal’dar support him and they are the largest single block; but there are many subcultures that have their own traditions and aspirations. The Marguul are one example that’s been called out in canon, but there’s many more like this—dar immigrants who have come to the region with their own traditions. Notably, in Kanon I have a goblin culture from deep in the Khraal rain forest that is quite different from the Ghaal’dar, who came from the mountains and caverns. Nonetheless, this shouldn’t result in a nation with the highest population of any nation outside of the main five. By the standards of the ECS—so again, ONLY FOR THE PURPOSE OF COMPARING IT TO OTHER NATIONS—I’d set the population of Darguun at around 230,000. That’s significantly higher than Valenar and on par with Q’barra or Zilargo, but less than a tenth of one of the Five Nations, and low enough to reflect the idea that most of the cities in the region are still unclaimed ruins.

That’s all for now! Because this is an IFAQ, I will not be answering further questions on these topics, but feel free to discuss your thoughts and ideas in the comments. And if you want support the site and pose questions that might be answered in future articles, join my Patreon!

Eberron: Rising From The Last War says that in the Eldeen Reaches, “communities include awakened animals and plants as members.” This raises a number of unanswered questions. Are these awakened beings considered to be citizens under the Code of Galifar? How common are awakened animals in the Reaches? Have they ever been hunted like normal animals? As always, keep in mind that what follows is what I do in my campaign based on my interpretation of the awaken spell—your mileage may vary.

The act of awakening an animal or plant isn’t about evolution. The caster doesn’t create a new species of sentient animal with a single spell. Instead, awaken shapes a sentience from the collective anima of the world and fuses that with the subject, creating a unique intelligent entity; it’s not unlike summon beast, but the spirit is infused into an existing body instead of having a conjured physical form. The awakened creature can access the memories of their life before awakening, but they are a new and unique entity. Critically, if a druid awakens two rabbits, their offspring aren’t sentient. So there aren’t vast lineages of awakened animals out in the world. Every awakened animal has a direct connection to a powerful spellcaster. Druids and bards who can cast awaken are rare, and the spell also has a significant casting cost; it’s not something that is ever done trivially.

So awakened animals and plants are found in Eldeen communities. But any time you encounter one, it’s worth asking who awakened this animal and why? Here’s a few answers.

If they’re citizens of the Eldeen Reaches, definitely. In my campaign, becoming a citizen of the Reaches involves swearing an oath of allegiance to a druidic representative—I don’t have time to develop all of the details, but it’s largely saying that you swear to abide by the laws of your community and the Great Druid, and that you will protect the Reaches and its people in times of trouble. The key point here is that in the Reaches, awakened animals are treated like any other sentient creature. While they’re often found performing specific jobs, again, they aren’t slaves and they can quit any time they want. They’re fellow citizens of the Reaches, and if you commit a crime against one, it’s no different than committing a crime against any humanoid. If you kick a dog in a Reacher villager, he could go to the council and accuse you of assault, and if you shoot Bambi the awakened deer, it’s murder… though it’s worth asking why did someone awaken a deer? It definitely could happen in Greensinger territory, but an awakened deer would be very unusual elsewhere. Now, the trick is that while an awakened dog may be a citizen of the Reaches and thus entitled to the protection of the law in Sharn, you’ll have to convince the Sharn Watch of that, which may take some doing. On the other hand, there’s a giant owl on the Sharn Council, so who can say!

As a side note, while we often talk about Oalian as being an awakened tree, the rituals and power invested in the Eldeen Ada were more significant than the basic awaken spell. One aspect of this is that standard awakened plants can move around. In my campaign, Oalian is stationary and infused with primal power; they’re more than just a smart tree.

The people of the fields haven’t abandoned the use of metal. With the exception of some extremist Ashbound, there’s no inherent taboo against metalworking; metal comes from the soil, after all. The Wardens of the Wood seek balance between the wild and civilization, not to eradication industry entirely. The goal is to reduce the environmental impact of industry; scope may be reduced, and primal magic may be employed in place of destructive mundane techniques. Primal magic can help locate objects, shape or mold earth and stone, and when it comes to smithing, anyone who’s fought a druid knows that primal magic can be used to heat metal. The Reaches aren’t primitive; they are a primal civilization, and the key is to consider what tools primal magic can offer.

So the Eldeen Reaches are reshaping the industries of the east, but they haven’t abandoned them. The people of the fields still refine and work with metal, producing similar weapons and armor to those their Aundairian ancestors created. On the other hand, the people of the Wood have long had access to interesting materials aside from metal, and have primal techniques for shaping and strengthening wood, hide, stone, and bone to make it the equal of metal (if not superior to it, as with bronzewood and darkleaf presented in the ECS). So here’s a few options to consider…

So an Ashbound champion might wear armor fashioned from the hide of a horrid bear and wield a two-handed macuahuitl embedded with its teeth… but due to the techniques of the Ashbound artisans, these things would be the equivalent of a breastplate and greatsword.

That’s all for now! Thanks again to my Patreon supporters for making these articles possible. I won’t be answering further questions on this topic, but please discuss your own ideas and how you’ve used awakened animals in your campaigns!

There’s no shortage of questions concerning the Eldeen Reaches, and I decided to answer a few more.

For the past forty years, the Eldeen Reaches have officially been under the protection and guidance of Oalian, the Great Druid of the Wardens of the Wood. Long dominant in the forest, the Wardens have spread out into the plains to ensure order throughout the region. Each village has a druid counselor who provides magical assistance and spiritual guidance, and who advises the leaders of the community. Councils made up of representatives from each farming family govern each of the communities. Bands of Warden rangers patrol the forest, responding to threats as they arise.

The shifter tribes and druid sects have their own customs, but leaders are usually chosen based on age and spiritual wisdom. Concepts of law are guided by the ways of nature, and justice is usually swift and harsh.

Politically, the folk of the Eldeen Reaches largely ignore the events of the east and are ignored in return. The Wardens of the Wood have made clear to Breland and Aundair that they will defend the nation against any military threat and have no interest in further discussions regarding borders, treaties, or resource rights.

Eberron Campaign Setting

These are the basic facts as laid out in the Eberron Campaign Setting. The Reacher communities are self-governing. Druidic advisors help guide the villages, and the Wardens of the Wood act as the connective tissue, “preserving order throughout the region”. Each community sets its own rules, inspired by the sect its aligned with. The Code of Galifar is a good general model; most things considered crimes in Sharn will probably be crimes in Varna. On the other hand, a village that’s embraced the teachings of the Children of Winter may have unusual ideas as to what constitutes a proper trial. The main point is that it’s very much what we’d consider frontier justice, with the Wardens acting as sheriffs and communities largely relying on the hue and cry–on people being ready to come together to help when a crime occurs. Meanwhile, the tribes of the Deep Wood generally respect Oalian and the Wardens, but only a few have chosen to become a full part of the Reacher experiment, and most still maintain the same traditions they’ve followed for centuries, ignoring the world beyond the Wood.

Politically “the folk of the Eldeen Reaches largely ignore the events of the east and are ignored in return.” Sharn: City of Towers specifically notes that the Eldeen Reaches don’t have any sort of consulate in Sharn and Five Nations says that they’ve rebuffed diplomatic contact with Aundair. But never forget that this is an experiment. The Treaty of Thronehold is only two years old; the Reaches are still figuring out what it means to be a nation, and how to play at politics. So at the moment, they don’t do much of it; they “largely ignore the events of the east” and “have no interest in further discussions.” But depending what happens in the days and years ahead the Reachers may realize that they have to forge stronger ties to other nations, and have to get better at the game of diplomacy. If adventurers have ties to the Reaches, they could be instrumental in helping to establish or protect the first Eldeen embassies.

The Towering Wood hasn’t been explored in depth in canon. Canon sources say that they are preternaturally fertile and that the forces of magic permeate the wood. We’ve mentioned greatpines and “awe-inspiring” bluewood trees. Reflecting my last post, the Eberron Campaign Setting has this to say…

The deep woods of the Eldeen Reaches remain mostly as uncultivated and pure as they were when the world was young. In the Age of Monsters, when the goblinoids forged an empire across Khorvaire, the Eldeen Reaches were the domain of orcs who sought to live in harmony with the wilderness. The orcs were devastated in the war against the daelkyr. As a result of this terrible conflict, the forest was seeded with aberrations and horrid creatures formed by the sinister shapers of flesh.

In my campaign the Towering Wood is surrounded by a buffer zone—a few miles of woodland where the trees are smaller, where there are certainly predators but where you aren’t as likely to piss off a dryad or encounter horrid wolves. The people of the fields have always hunted game and harvested lumber from this region, and it’s likely grown thinner over the history of Galifar. But the people have always known that there’s a line you don’t cross. Because when you reach the Wood itself… you feel that capital letter. You can feel its age and its power. And you if you blunder into it without knowing your way… Fey. Fiends. Aberrations. Plants twisted by Avassh. Undead. Horrid animals. Feral gnolls. Lycanthropes. Until a decade ago, Sora Maenya. If you just randomly chop down a tree, you might be cutting into Old Algatar, the great interconnected Eldeen Ada who will surely lay a terrible curse upon you or send a treant to crush you. And set aside all of these supernatural threats: if you just brought in a team to start cutting down bluewoods, you’d have to deal both with the Ashbound and the Wardens of the Wood; one of the prime directives of the Wardens is to protect the Wood from the outside world. It’s entirely possible Cannith has tried harvesting in the Towering Wood in the past; it’s just never ended well.

With that said, people live in the Towering Wood. The key is that you have to understand the threats, to be able to recognize warning signs, to know the locations of manifest zones and the safe paths maintained by the Wardens of the Wood. Looking to the present day, the Eldeen farmland communities work with their druidic advisors to harvest lumber from the edge of the Towering Wood, both ensuring that their actions are sustainable and that the lumberjacks don’t blunder into a dryad’s grove or one of Avassh’s bone orchards. Anyone can hunt and harvest from the Towering Wood… it just requires care and understanding.

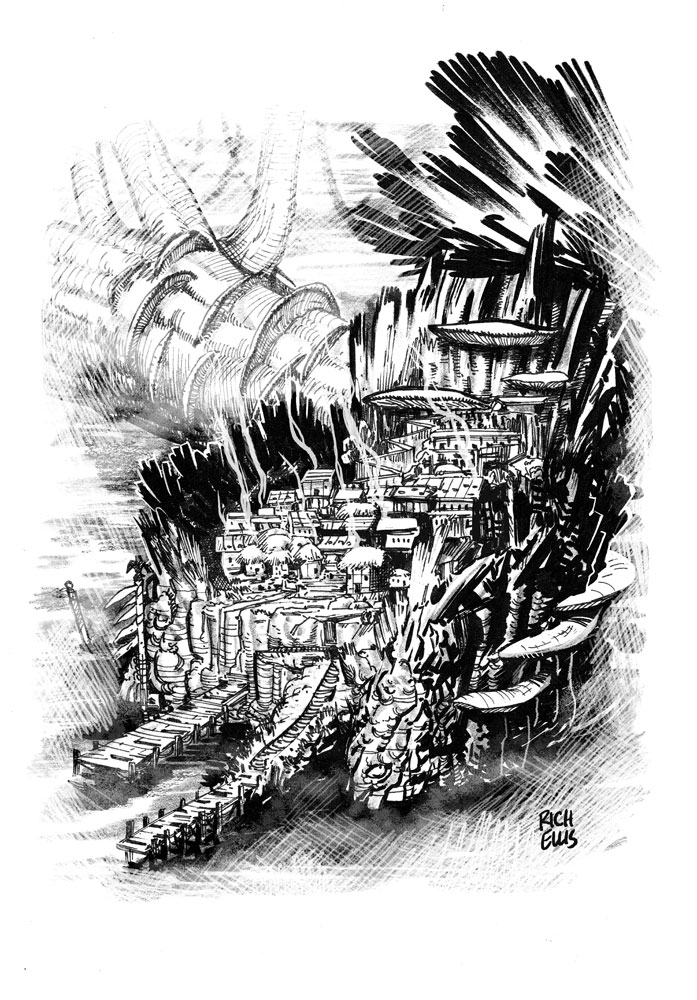

But is the Wood actually like? For a start, it holds trees that don’t exist in our world. Greatpines are similar to the pine trees we know, but have thicker trunks and can reach heights of over 250 feet. The awe-inspiring bluewoods are more massive than our redwoods. But as you go deeper, you can encounter something different. This is a point where I break with canon—keeping the same general idea, but shifting it slightly. The ECS describes a specific region called The Guardian Trees, where the trees “dwarf the greatest redwoods”—but this is a very specific region that only spans about 30 miles. In my campaign, I take a different approach. First, I use the term guardian tree to refer to the Eldeen Ada. Second, in my Towering Woods those immense trees aren’t limited to a tiny region; they are spread across the forest. I call them titans—primordial trees that dwarf anything in our world, potentially thousands of feet in height. These titans are infused with primal energy—there’s the possibility they are literally the first trees, so they are sustained beyond what should be possible for any mundane fauna. The article I linked is tied to my Phoenix: Dawn Command setting, in which the titans have all fallen. In the Towering Wood I’d say most of the titans are still standing, but that there are a few that have fallen. This allows for the possibility of stumptowns (as pictured above, communities in the stumps of titans) or for communities or dungeons carved into the densewood trunks of fallen titans. Unlike the ECS, I spread these throughout the wood, but they are still rare; there’s a few dozen of them in total across the entire Wood. But each one is a truly remarkable landmark, and a wellspring of primal power. Traditional magic doesn’t work on a titan, so you can’t just animate one of them. Some people believe that the titans are awakened but are simply too vast to perceive humanoids; others believe that they hold the spirits of all the druids who’ve died in the region. Either could be true. To date Avassh hasn’t corrupted a living titan… but it could certainly have infested the trunk of a fallen one.

A final important point is that the map as it stands doesn’t show any rivers or bodies of water in the Towering Wood. This is solely because the maps have low resolution. Rivers and streams flow down from the mountains and through the wood, and there are pools tied to Lamannian and Thelanian manifest zones. There’s nothing on the scale of Lake Galifar or Silver Lake, but there are certainly immense ponds and streams that can prove challenging to cross.

The people of the woods hid from the eyes of Galifar, and most prefer the solitude of the Towering Wood to the bustle of the Five Nations. Shifters and centaurs sometimes live in their own isolated tribes, but the forest folk prefer to live in small mixed communities—human, elf, and shifter living side by side. They follow the faith of one of the druid sects, but only the most exceptional… join the patrols that guard woods and plains alike.

Player’s Guide to Eberron